Happy birthday, Larry Rivers. You’d have been 99 today.

Yitzchoch Grossberg, your given name, translates as Isaac Big Mountain

(on the model of Giussepe Verdi equals Joe Green)

and I love you and your saxophone, and how

you sang “Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me” in the green room

with Ashbery, Koch, and Jane Freilicher

for an event at the New School that I organized

and moderated, and I hope they taped it.

When was that? 1998? 1999?

At the Knickerbocker, Larry Rivers and the Climax Band played

and you sang: “I’m afraid the masquerade

is over, and so is love,” but our love is here to stay,

and I wish you were here to hear me say it.

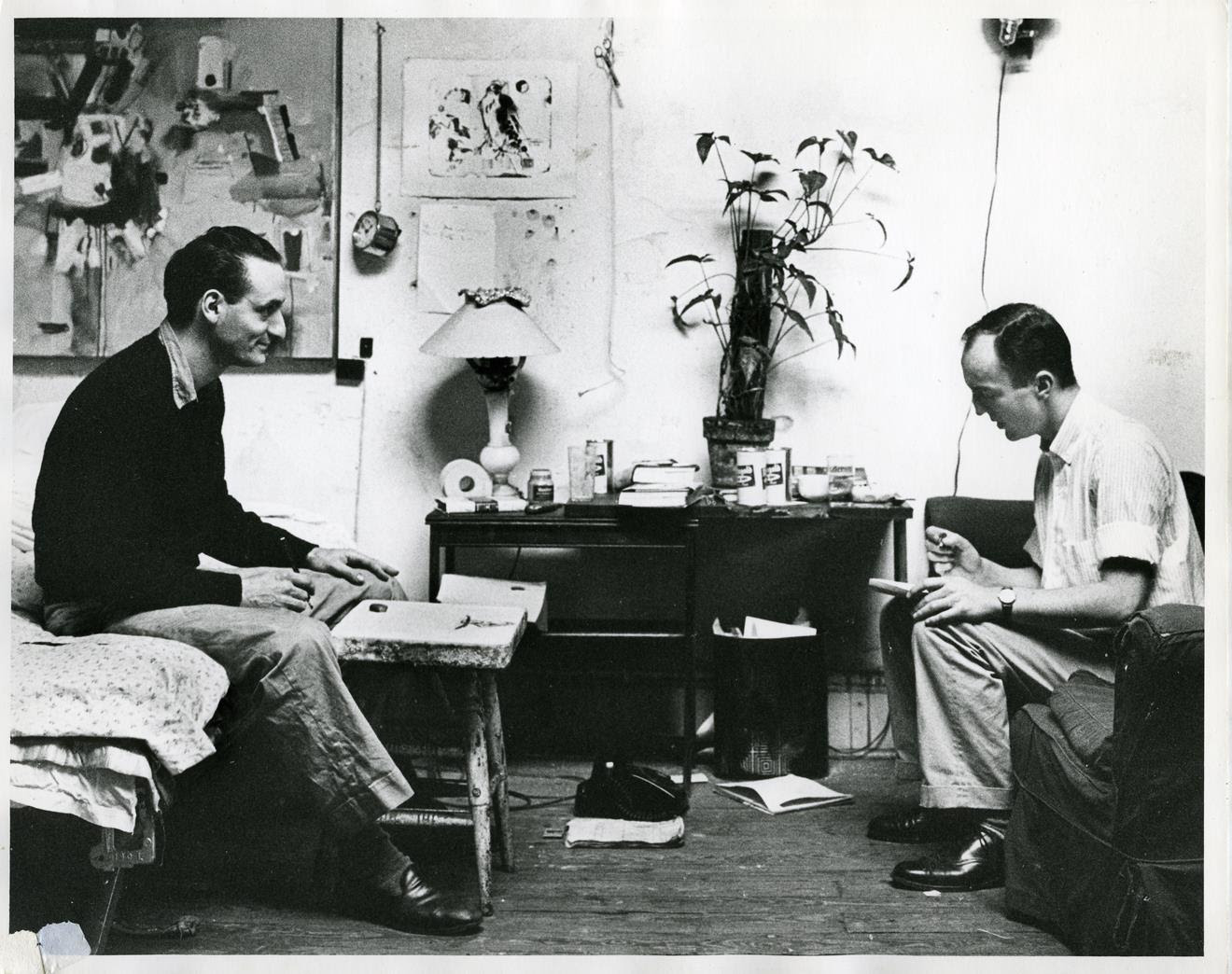

Read about this wonderful painter here or below the picture, which is a detail of a larger photo from the late 1950s, in which, facing Larry, is Frank O’Hara. Tthey were collaborating on Stones, the poems and drawings that were released in an edition of twenty-five (described as a “portfolio of 12 lithograph[s] and title page on linen rag paper”) that would set you back $45,000 were you to try to buy a copy today. On the table beteen the artistic collaborators are cans of Rheingold, the dry beer.

“A Master of Rhythm and Hues”

by David Lehman

Washington Post, December 27, 1992

LARRY RIVERS’s life is as colorful as the spectacularly original canvases that have firmly established his place among the major avant-garde artists of our time. Born Yitzroch Grossberg in the Bronx, Rivers was an uninhibited, grass-smoking, sex-obsessed jazz saxophonist in his early twenties when he picked up a paintbrush for the first time. The year was 1945; the war was about to end, and New York City was on the cusp of becoming the art capital of the world.

Encouraged by such estimable painters as Jane Freilicher and Nell Blaine, Rivers soon “began thinking that art was an activity on a ‘higher level’ than jazz,” because music is “abstract” and can’t be done alone whereas painting is a solo performance that allows the artist to “make nameable things.” Rivers took drawing classes with the great Hans Hofmann, but he always retained the improvisatory ideal of jazz, and the make-it-up-as-you-go-along approach has served him well. Even his most monumental constructions, such as “The History of the Russian Revolution” (1965) in Washington’s Hirshhorn Museum, have a fresh air of spontaneity about them, as if they had just been assembled a few minutes ago.

Rivers had a meteoric rise. A Pierre Bonnard exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1948 proved to have a decisive influence on his sense of color and composition. No less an eminence than Clement Greenberg, then the nation’s foremost art critic, declared in 1949 that Rivers was already “a better composer of pictures than was Bonnard himself in many instances” — and this on the basis of Rivers’s first one-man show. Though Greenberg would later modify his praise and then withdraw it altogether, he had launched the career of “this amazing beginner.”

If one condition of avant-garde art is that it is ahead of its time, and another is that it proceeds from a maverick impulse and a contrary disposition, Rivers’s vanguard status was assured from the moment when, at the height of Abstract Expressionism, he audaciously made representational paintings, glorifying nostalgia and sentiment while undercutting them with metropolitan irony. His pastiches of famous paintings of the past — such as his irreverent rendition of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” (1953) — seemed to define the playfully ironic attitudes of post-modernism years before anyone had thought up that term. And his paintings of brand labels, found objects, and pop icons — Camel cigarettes, Dutch Masters cigars, the menu at the Cedar Bar in 1959, a French 100-franc note — demonstrate what is vital about Pop Art while escaping the limitations of that movement.

Rivers has his own style of painting: He relies on “charcoal drawing and rag wiping.” Also distinctive is his prankish sense of humor. In 1964 he painted a spoof of Jacques-Louis David’s famous “Napoleon in His Study,” the portrait of the emperor in the classic hand-in-jacket pose. Rivers’s version, full of smudges and erasures, manages to be iconoclastic and idolatrous at once. The finishing touch is the painting’s title: Rivers called it “The Greatest Homosexual.”

“What Did I Do?,” Rivers’s autobiographical ramble, conveys the excitement, the nervous energy, and the sublime agitation of life in New York City at a time when rents were cheap, Lester Young was president of the republic of jazz, and painters of the caliber of Willem De Kooning and Franz Kline hung out at the Cedar Bar, which thus became, in Rivers’s phrase, “the G-spot of the art scene.” Obsessed with “art and the quest for sex,” Rivers left his wife for the floating Bohemia of Manhattan, where he shot up heroin, was openly bisexual, and lived with his two sons and his mother-in-law, Berdie, whom he painted — sometimes in the nude.

Rivers had (and has) an adventuresome spirit, an appetite for notoriety, and a nose for publicity. He won a lot of money on “The $64,000 Challenge,” one of the fixed television game shows of the 1950s, until he met his Waterloo when he was asked to identify the maiden name of Renoir’s wife. Later, Rivers made the most of his opportunity to testify at a grand jury investigation of the program, acting as if the courtroom were an extension of show biz by other means. One of the show’s producers, Rivers tells us, was his friend Shirley Bernstein, “sister of Lenny.” When Rivers denied that she had fed him the answers, the assistant district attorney fired back, “Why are you protecting her, Mr. Rivers?” In response, Rivers writes, he “rose from the witness chair and said dramatically, ‘Because I love her — and I don’t care if the whole world knows it!'”

Long on anecdote, short on analysis, “What Did I Do?” is full of juicy stories about Rivers’s friends and associates, and he seems to have been chums with aesthetic experimentalists of all stripes, from the Living Theatre’s Julian Beck and Judith Malina (“violent pacifists,” Rivers calls them) to John Cage (whose music “was like a sermon by Spike Jones”), Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, not to mention the poets of the New York School, with whom Rivers became fast friends: Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, John Ashbery, James Schuyler, Harry Mathews. He and O’Hara (“a charming madman”) were intermittently lovers. They collaborated on several inspired projects, such as a hilarious send-up of an art manifesto, “How to Proceed in the Arts”: “How can we paint the elephants and the hippopotamuses? How are we to fill the large empty canvas at the end of the large empty loft? You do have a loft, don’t you, man?”

Rivers is a world-class talker, and reading “What Did I Do?” is like listening to a candid, manic monologue. It is an experiment in discontinuous narrative, with frequent flashbacks and flash-forwards, and it is an awful lot of fun. It isn’t always easy to piece together the chronology — Rivers places his trust in memory, that least reliable of fact-checkers — but that isn’t the point. The real subject of this book — and its greatest pleasure — is the personality of the artist: mercurial, profane, madcap, somewhat exhibitionistic, sometimes puerile: a wiseguy who gets a kick out of shocking the censor.

In the book’s preface, Rivers introduces us to his collaborator on this project, the writer Arnold Weinstein: “I knew the three women he married, he probably slept with both my wives. What can I say? He’s an old pal.” That is the authentic Rivers tone, and it spices up every page. Some of his riffs are extraordinary. One of his sons is “deranged but normal in every other way.” Rivers and his second wife, Clarice, “parted in 1967 and have been married ever since.” Or consider this echo of the book’s title: “For someone who has always had fantasies of living in a whorehouse like my heroes Pascin, Lautrec, Van Gogh, and Utamaro, what am I doing with five children, adding up to 252 pairs of shoes, 1,008 boxes of cereal, hot and cold, 8,660 quarts of milk, etc., plus 23 analysts, including mine?”

David Lehman’s recent books include “Operation Memory,” a collection of poems, and “Signs of the Times: Deconstruction and the Fall of Paul de Man.”

A review of

“WHAT DID I DO? The Unauthorized Autobiography of Larry Rivers”

By Larry Rivers with Arnold Weinstein

Aaron Asher/HarperCollins

498 pp. $30

Go to Source

Author: The Best American Poetry