Unlock the Hidden Truths: How Your Self-Description Reveals More Than You Think

Ever stared at your own reflection, wondering how on earth you're supposed to describe yourself…

Discover the Hidden Truth Behind Joseph Romano’s Poem “You’re My Reason for Living” That Will Change How You See Love Forever

Isn’t it something extraordinary when a face shines so brightly it feels like the sun’s…

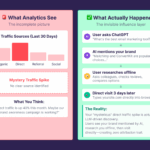

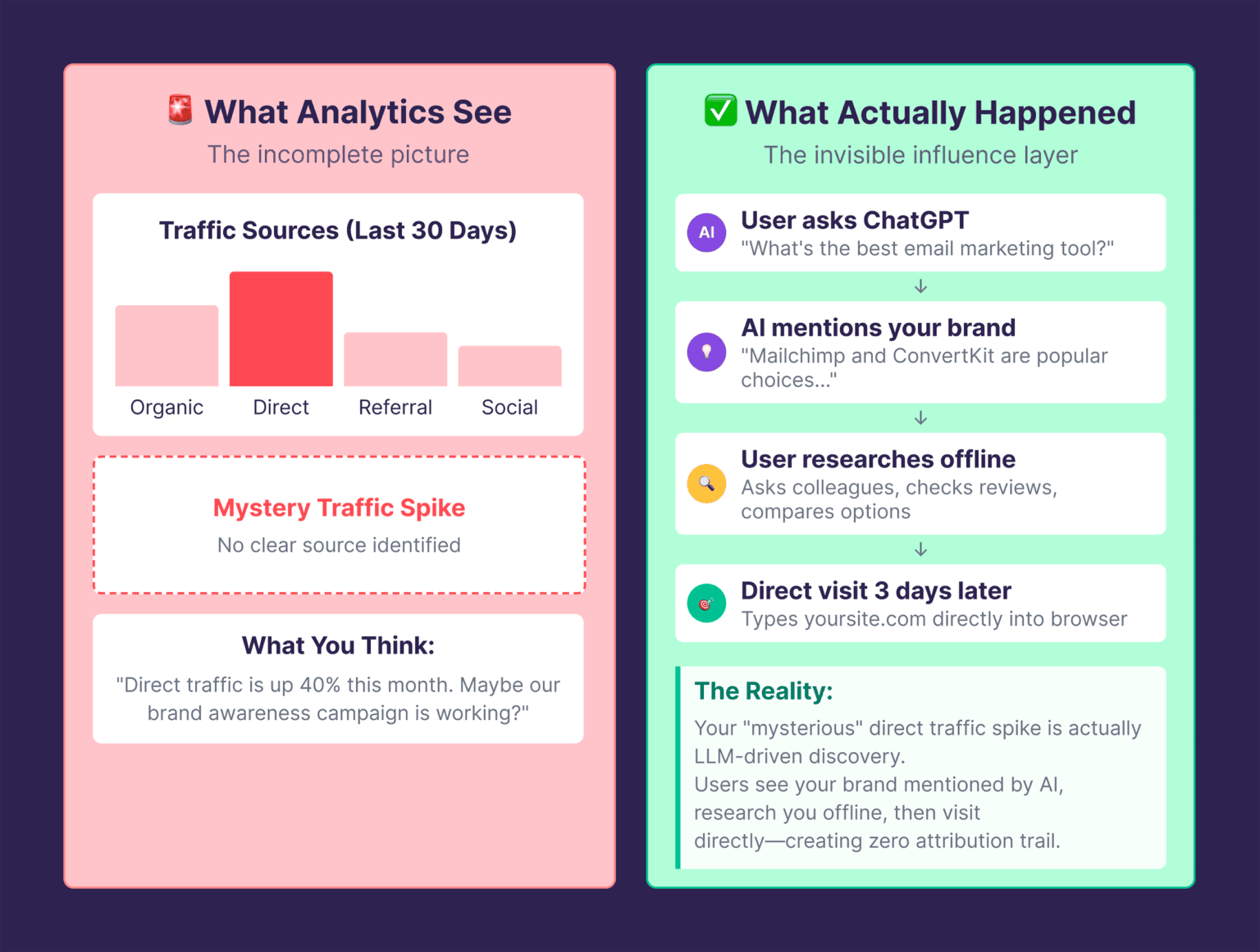

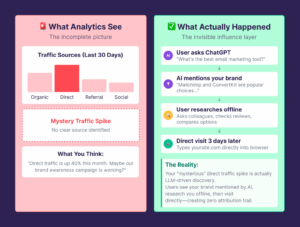

The Hidden SEO Metric Behind LLM Success That Experts Are Keeping Secret

Ever noticed how your Google traffic takes a nosedive, yet more folks are Googling your…

Why Breaking Grammar Rules in Poetry Could Be the Secret to Masterful Verse

Ever wondered if breaking grammar rules in poetry is like an acrobat daring a dizzying…

Unraveling Desire: The Fiery Secrets Within G. S. Katz’s “Passion Collision”

Ever paused to wonder how a stolen kiss—half-held and half-withheld—can linger like a shadow from…

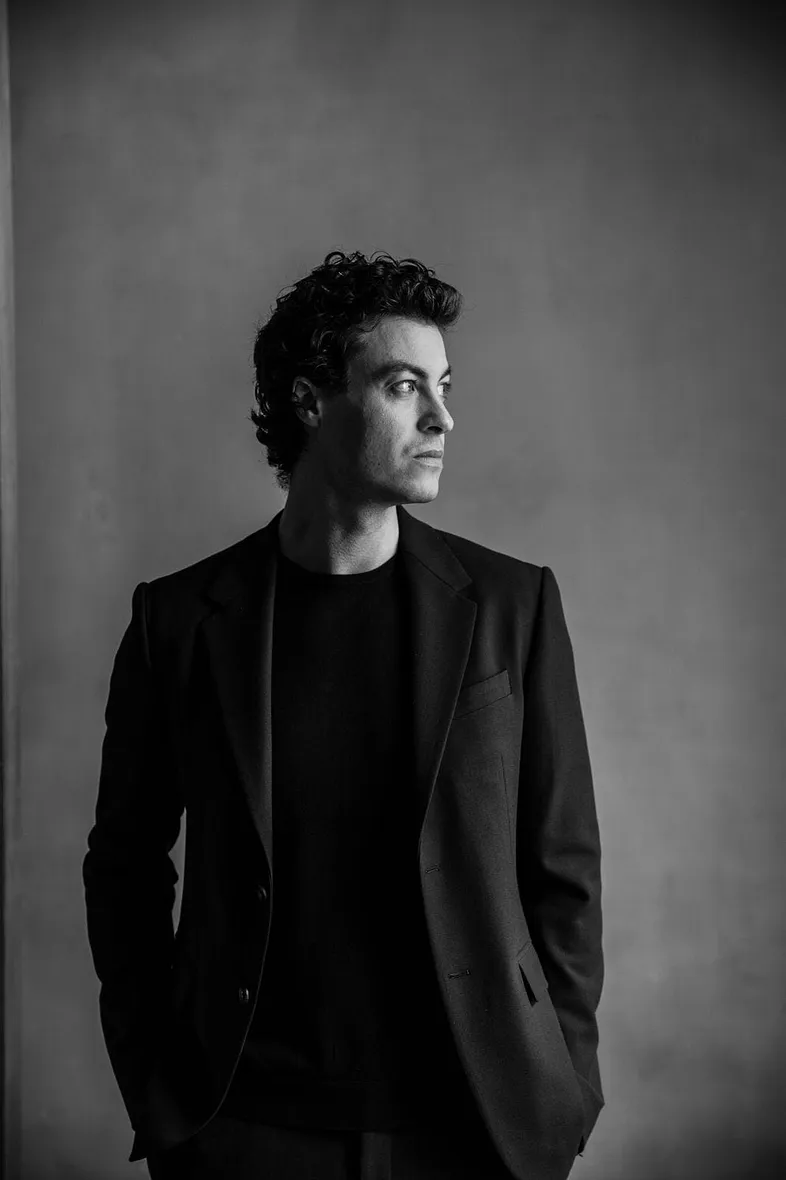

Uncovering the Untold Secrets: Miguel Flatow Reveals What Drives His Storytelling Genius

Ever wondered what it takes for a screenplay to land on the highly coveted Black…

Discover California’s Hidden Gems: Untold Adventures Await Amateur Travelers!

Ever wondered if your knack for storytelling could pay your coffee bill—while you explore the…

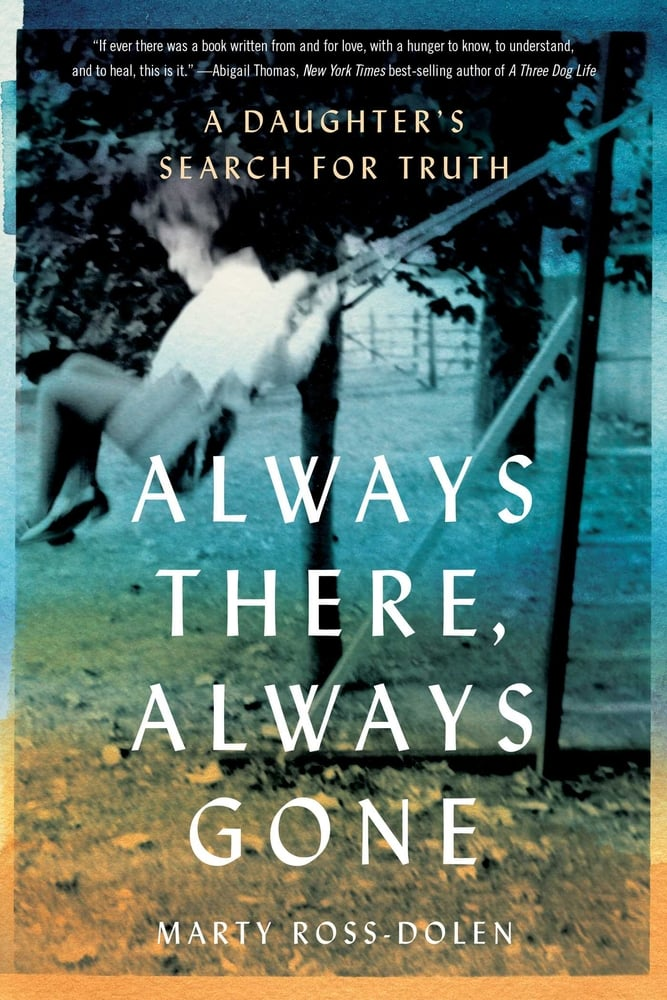

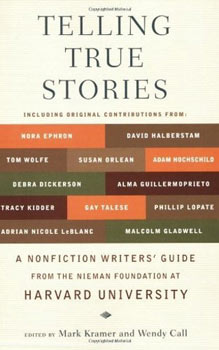

Uncover the Hidden Secrets Behind Mark B. Perry’s Writing Mastery – Are You Ready to Write Now?

Ever wonder what it’s like to juggle the wild worlds of Emmy-winning TV writing and…

Uncovering the Unseen Twists: When Nothing Ever Changes, Yet Everything Mutates

Ever caught yourself pondering if anything really changes in this whirlwind we call life? Dick…

The Secret Symbolism Behind Lou Reed’s Choice to Never Wear Brown Revealed in G. S. Katz’s Poem

What is it about Lou Reed that so effortlessly drags us into the gritty, shadowy…