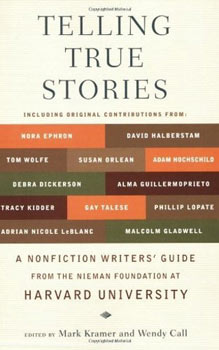

Unlock the Secret Power of the 4 Cs—Why Mastering Them Could Change How the World Reads You Forever

Ever find yourself tangled up in words, wondering why expressing a simple thought feels like…

The Unexpected Melody That Healed a Lifetime of Heartache—Discover the Robin’s Secret Song

Have you ever paused mid-step, caught off guard by the simple, soulful trill of a…

Unlock the Secret Method to Perfect Writing—No AI Required!

Ever feel like your trusty grammar checker has turned into an overzealous robot buddy who…

Unveiling the Hidden Strength Within: The Enigmatic Power of “The Rhino Skin” by P.K. Deb

Ever felt like throwing on an invisible suit of armor just to survive the daily…

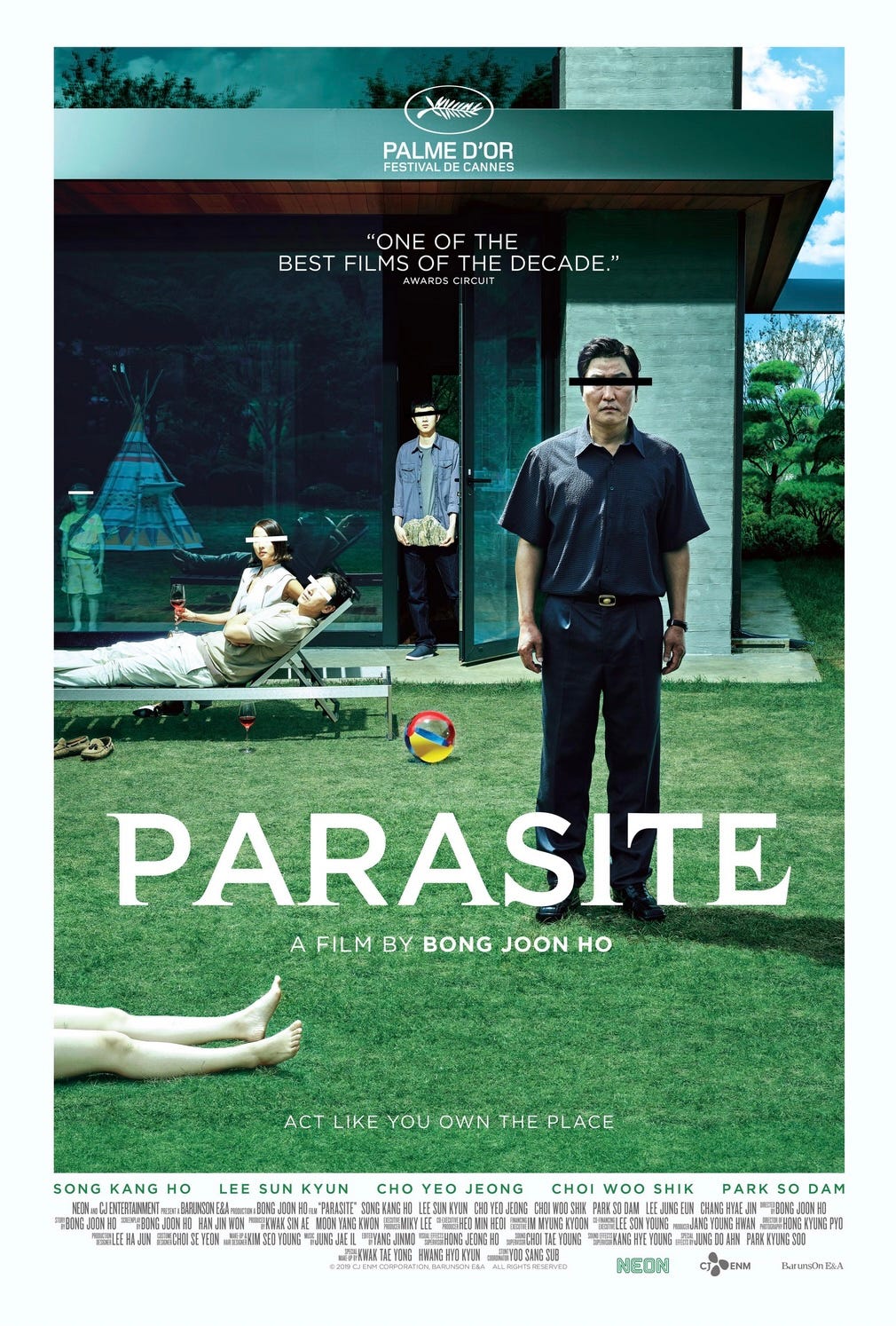

Unlock the Hidden Secret That Transforms Your Spec Script from Good to Unforgettable

Ever wonder why writers keep chasing that elusive "spec" project despite the odds stacked like…

Escape Reality: How a Writer’s Workshop Transforms Your Vacation into a Creative Journey

Ever wonder what happens when a writer trades the familiarity of the Rocky Mountains for…

Unveiling the Enigmatic Passion Behind “The Lover of Beauty” – A Poem That Transcends Time

Ever wonder if loving someone for their looks is like chasing a sunset—stunning for a…

The Hidden Truths Behind Childhood: A Poem That Parents Aren’t Meant to Read

Ever wonder how a simple journey from youth to adulthood can mirror the gritty realities…

Unlock Hidden Remote Writing Gigs for 07/05/2025 You Didn’t Know Existed!

Ever wonder if you’ve got what it takes to crank out a gripping story in…

Exposed: Shocking Secrets Behind International Impact Book Awards Revealed by Insider Larry Bergeron

Ever get one of those emails that sounds just a bit too good to be…