As we fast approach the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, it is possible to argue that we are living in the age of post-everything: post-modernism, post-ideology, and even, possibly, post-cinema. Are we now in an age when the dominant—indeed, almost universal—art form of the 20th century is, well, just another art form?

The 3 Great PSAs (Public Storytelling Art Forms): Theater, Opera, and Cinema

To understand post-cinema, it is necessary to consider where it has come from. It was the third, and by far the most popular, of the three great public storytelling art forms (or PSAs, to use a pre-existing acronym) of the last four hundred years: theater, opera, and cinema.

Theater, of course, is the oldest of the three, dating back to Western civilization to the Ancient Greeks. In Eastern or Asian civilization, it goes back even further, with Indian theater, thought to be the oldest in the world, having developed its combination of dance and drama, which was comparable to Ancient Greek theater, by about the 8th century BC or BCE.

However, theater was virtually reborn in England, and eventually in the rest of Europe and the world by the singular genius of Shakespeare. His popularity prompted a boom in theater and particularly theater-building at the end of the 16th century AD that made theater a much more publicly accessible and popular art form than it had ever been before.

‘Shakespeare in Love’ (1998)

The first opera is thought to be Jacopo Peri’s Dafne, and the first great opera is generally accepted to be Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo, with Monteverdi providing the same kind of creative thrust to bring opera to life (and the masses, or at least large audiences) that Shakespeare did in the theater.

Theater and opera co-existed for the next 250 years. Eventually, both were overtaken in scale, reach, and influence by cinema at the end of the 19th century. Initially a sideshow or carnival-esque entertainment, largely reliant on the sheer novelty of showing moving pictures for the first time, by the start of the 20th century cinema had surpassed, indeed almost overwhelmed, the popularity of theater and opera.

At cinema’s commercial high-point, which was roughly between the end of the Silent Era in 1927 and the Stock Market Crash in 1929, it was estimated, for example, that 90 cents of every American’s entertainment dollar was spent on going to the movies. Although reliable audience information for that period is almost impossible to establish, there is no doubt that cinema was by far the biggest mass-market entertainment or art form that there had ever been.

Read More: Five 21st Century Plays Every Screenwriter Should Know

Cinema’s Rise Dominance, Especially Television

Of course, at that time, some thought that cinema had effectively “died” with the arrival of sound, which meant that it was no longer a purely (or almost purely) visual storytelling medium. The Stock Market Crash of the 1930s and the ensuing economic chaos had far-reaching consequences, including the rise of Nazism in Germany and its spread across Europe, culminating in World War II. Naturally, these events had a profound impact on cinema audiences.

Nevertheless, after WWII and with the rebuilding of Europe and the US post-war economic boom, cinema audiences largely recovered. After the 1950s, the real challenges to cinema’s dominance came.

The first was the arrival of television in the early 1950s. Billy Wilder famously joked that TV made movies look far better; they were no longer the runt of the artistic litter. Of course, cinema responded to the coming of TV with the successful introduction of color, especially Technicolor, and with less successful techniques such as 3-D. And it did so thematically, with self-consciously “big” films about “big” subjects, such as the Biblical and Roman Epics of the late 1950s, which were thought to contain spectacle so gigantic that it just could not be appreciated on a small screen.

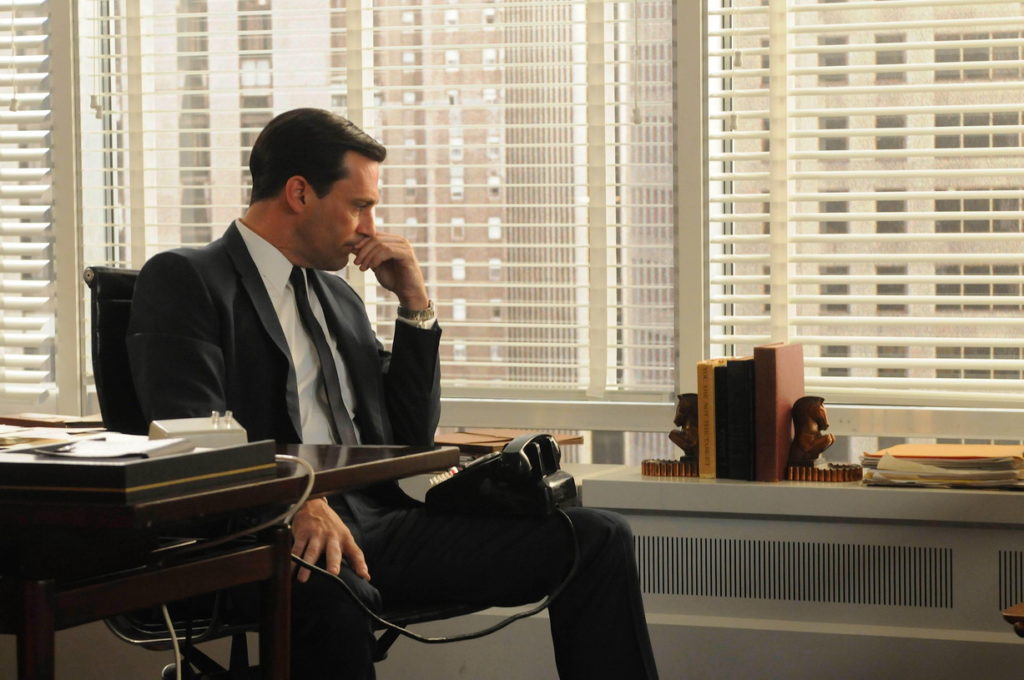

In microcosm, the relationship between TV and movies at that time can be seen in the character of Don Draper in Mad Men, the ad man who hates TV (even though he begrudgingly comes to appreciate its importance to advertising) but loves going to the movies, to the extent that he often ducks out of creative meetings to go to them.

It is an adage that new media do not replace old media but simply add to them.

‘Mad Men’

TV did not kill off cinema. That was especially true when the French New Wave movement brought more personal, more artistic moviemaking in the streets rather than in the studios, leading to the Second Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1970s. That was when Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and more produced both artistic masterpieces (The Godfather films and Chinatown) and mass-market entertainment, or “blockbusters” as they were dubbed for creating queues for cinemas that stretched around city blocks (Jaws and Star Wars).

Arguably, it was not TV that killed, or at least dramatically reduced, cinema but its offspring, video, which came onto the mass market at the end of the 1970s and the early 1980s. It was video, which allowed ordinary people to watch movies at home in a way that before then had only been the preserve of Hollywood moguls, that broke the all-important link between cinema and the public and collective viewing of it.

It was obvious that movies were smaller on TV or video screens than they were in the cinema, with a consequent effect on the viewer’s dramatic immersion in them.

But what was less obvious then, although it is increasingly obvious now, was that people were no longer seeing movies together, in large numbers, but alone, or at best in small family groups or circles of friends.

Read More: 3 Things Television Writers Can Learn from TV Episode Recaps

‘Jaws’ (1975)

It’s Not Streaming but “Screening” That Has Changed Cinema

Of course, the advent of streaming over the last decade, which was accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic when everyone everywhere was trapped at home, has only increased those two related trends, whereby 20th-century cinema—films shown on big screens to large audiences, watching them together—has largely given way to post-cinema—films shown on much smaller screens (and now even relatively tiny mobile or cell phone screens), and viewed either singly or at most in very small groups.

However, streaming has only intensified the trends. What has arguably been even more damaging to the cinema—the watching of films, in whatever context or on whatever size of the screen—is what might be called “screening.”

Ironically, “screening” is not, as the name might suggest, some form of protection but rather the almost complete lack of protection from screens that we now take completely for granted.

Screens of one kind or another are now so ubiquitous that we are almost unaware of them, from their use in the workplace to their near-total domination of our private and social lives, especially among young people. Specifically, it is the element of control that comes with these ubiquitous screens that are possibly damaging to the traditional—indeed, once-universal—idea of cinema.

I know this from my children, who are quintessential 21st-century “digi-kids.” Like most parents of teenagers, I have found myself in recent years feeling that I have increasingly little in common with them. For example, my 18-year-old son much prefers UFC (Ultimate Fighting Challenge), MMA (Mixed Martial Arts), and all their variants to the older, traditionally popular sports such as football (including American football), rugby, cricket, or baseball.

That process extends to film or, more precisely now, to moving images. Whereas I love immersing myself in a movie, literally surrendering myself to it, he and many of his generation find that limiting, or more specifically “boring.” Without the ability to interact with a story or narrative of some kind that is hard-wired into almost every other form of screen activity—gaming, social media, YouTubing—he is not nearly as interested in cinema or movies as I am.

‘Red Notice’ (2021)

Public Storytelling Has Given Way To Private Interaction With Screens in Post-Cinema

It is that third element—the element of control—that has possibly been decisive in how cinema has changed in the 21st century from how it was throughout almost all of the 20th century.

Most films are now viewed on much smaller screens than they were in the past; we now watch films either in isolation or in small groups, rather than in large, indeed mass, audiences; and, crucially, I believe, we are now increasingly unable to surrender or give ourselves to films in the way that we once used to.

When we watch a film on a small screen of any kind, we have control of it in a way that we do not when we see a film in a cinema or movie theater. We can pause it, rewind it, fast-forward it; in effect, it is as if we are the film’s director or at least projectionist. Of course, that has considerable benefits, providing greater ease and comfort.

‘Rye Lane’ (2023)

However, what it also means is that we are in control of the film, and the film is not in control of us. When we wonder why films no longer seem as transportive or transformative as they were in the past, that may be the major reason. Our desire for control over them has, in turn, meant that they can no longer have anything like the same control over us.

It is that element, even more than the vastly reduced screens or vastly reduced audiences, that may be the crucial, indeed determining, factor in why we are arguably in the age of post-cinema. That does not mean that films—even great films—will not be made in the future. But it does mean that they are likely to be qualitatively different from how they were in the past and many ways far less of a spectacle or pure storytelling experience.

Read More: Broadcast, Cable, or Streaming Networks: What’s Best for Your Idea?

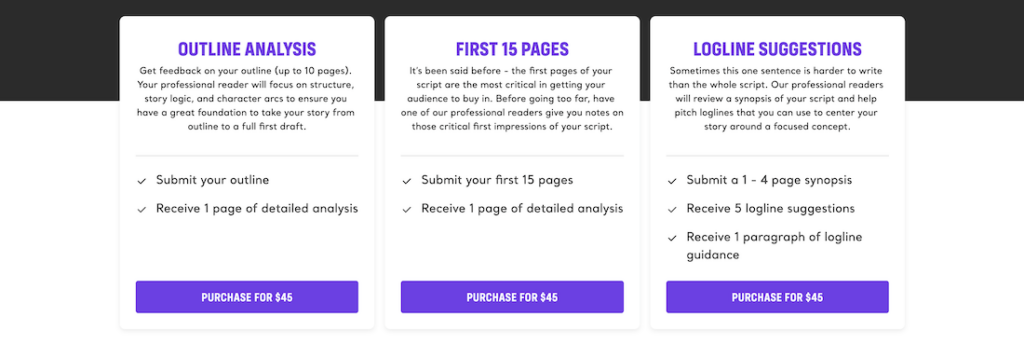

CHECK OUT OUR PREPARATION NOTES SO YOU START YOUR STORY OFF ON THE RIGHT TRACK!

The post Are We in the Age of Post-Cinema? appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Martin Keady