Béla Viktor János Bartók was born in the Banatian town of Nagyszentmiklós in the Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Sânnicolau Mare, Romania) on March 25, 1881.

By age four, he was able to play the piano fairly well. In 1888 — he was seven — his father died suddenly. Mom took Béla and his sister, Erzsébet, to live in Nagyszőkős (present-day Vynohradiv, Ukraine) then Pressburg (Pozsony, present-day Bratislava, Slovakia). There — age 11 — he gave his first public recital, playing a short composition entitled The Course of the Danube.

He began serious piano study at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest with István Thomán, a former student of Liszt. There he met Zoltán Kodály, who became his lifelong friend and colleague.

In 1903 — after hearing Strauss‘s Also Sprach Zarathustra and Ein Heldenleben — he composed his own tone poem, Kossuth — a magnificent work from the 22-year-old composer:

In 1908, he and Kodály traveled into the countryside to collect, research and record old Magyar folk melodies.

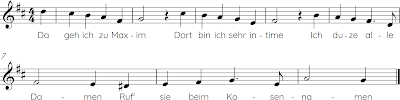

Muzsikás has recorded many of these folk tunes. This one is a Chassid wedding song:

Using unusual string techniques — sul ponticello, a new type of pizzicato (“snap”), massive glissandi — sometimes going in all four instruments — the Third, Fourth and Fifth string quartets are unqualified masterpieces.

He also developed a new kind of form — the arch. In the Fourth Quartet, the first and fifth movements, and the second and fourth, have similar relationships; while the middle movement can be roughly divided in two, thus creating a kind of arch form when viewing the work as a whole.

- The first movement revolves around a six-note chromatic motif that is chased around by the four players, a whirling dance which will come to its ultimate fruition in the parallel fifth movement.

- All four strings are muted, and in a bat-out-of-hell tempo, the music dances and flutters madly. This is extremely difficult music.

- The pace comes to a near standstill. First the cello, and then (at the approximate half-way point) the violin play a jittery motif on top of held chords.

- Like the second, this movement is certainly unusual. The players put down their bows, because the entire movement is played pizzicato.

- A rugged Hungarian dance, which erupts with passion and energy.

During the Nazi era, he stuck around as long as he dared. First sending his manuscripts out of the country, he reluctantly emigrated to the U.S., settling in New York in 1940.

Although well known as a pianist and ethnomusicologist, his compositions were not well known in America.

Contrary to popular myth, Bartók did not die in poverty. Although his finances were always precarious, he had friends and supporters who generously gave him enough to live on — but he was a proud man, and did not easily accept charity.

In the five years before his death in 1945, he became a very sick man. Leukemia went undiagnosed until April of 1944.

As his body slowly failed, his creative energy somehow increased. The masterpieces he composed in these years include The Sixth String Quartet, The Third Piano Concerto — and most of all, the Concerto for Orchestra — a magnificent, uplifting work — a staple of the orchestral repertoire today.

A curious little moment in the fourth movement:

Bartók quotes a recent quote from an much earlier quote:

Following this he writes harsh, trilling sounds, descending jokey clarinet quintuplets, and restates the theme with added little funny details — like smeary trombone glissandi — then restates and permutates them with even more humor …

Go to Source

Author: Lewis Saul

![Shards of Beauty: dust, stardust, sheep and wolves [By Tracy Danison]](https://writersdepot.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/715l1ecAH4w-768x432.jpg)