Unlock the Dark Secrets Behind Creating Villains Readers Can’t Forget in Just Five Steps

Ever wonder why some villains haunt us long after we close a book, while others…

Unveiling the Secrets of Mother Ocean: A Poetic Journey by Robert Zumbrun

Ever wonder how a poem could mimic the wild tangents in your brain, all while…

Can You Crack This Week’s WritersWeekly Trivia Challenge? Test Your Knowledge Now!

Ever wonder why some contests just grab your attention while others fade into the background?…

Unlock Hidden Remote Writing Opportunities You Won’t Find Anywhere Else – July 10, 2025 Edition

Ever wondered if you could craft a compelling short story, not in days or weeks,…

Unveiling the Hidden Truth: The Spellbinding Secret Within G. S. Katz’s Poem

Isn't it fascinating how a few words can ignite a wildfire of passion, setting our…

Exposing the Dark Secrets: Shocking Confessions from Publishing Scam Victims in Episode 14

Ever wonder how some writers effortlessly turn their passion into a thriving career while others…

The Shocking Truth Behind Sharing My Book Title With a Stranger Revealed!

Ever found yourself clutching the “perfect” book title — that gleaming nugget of genius you…

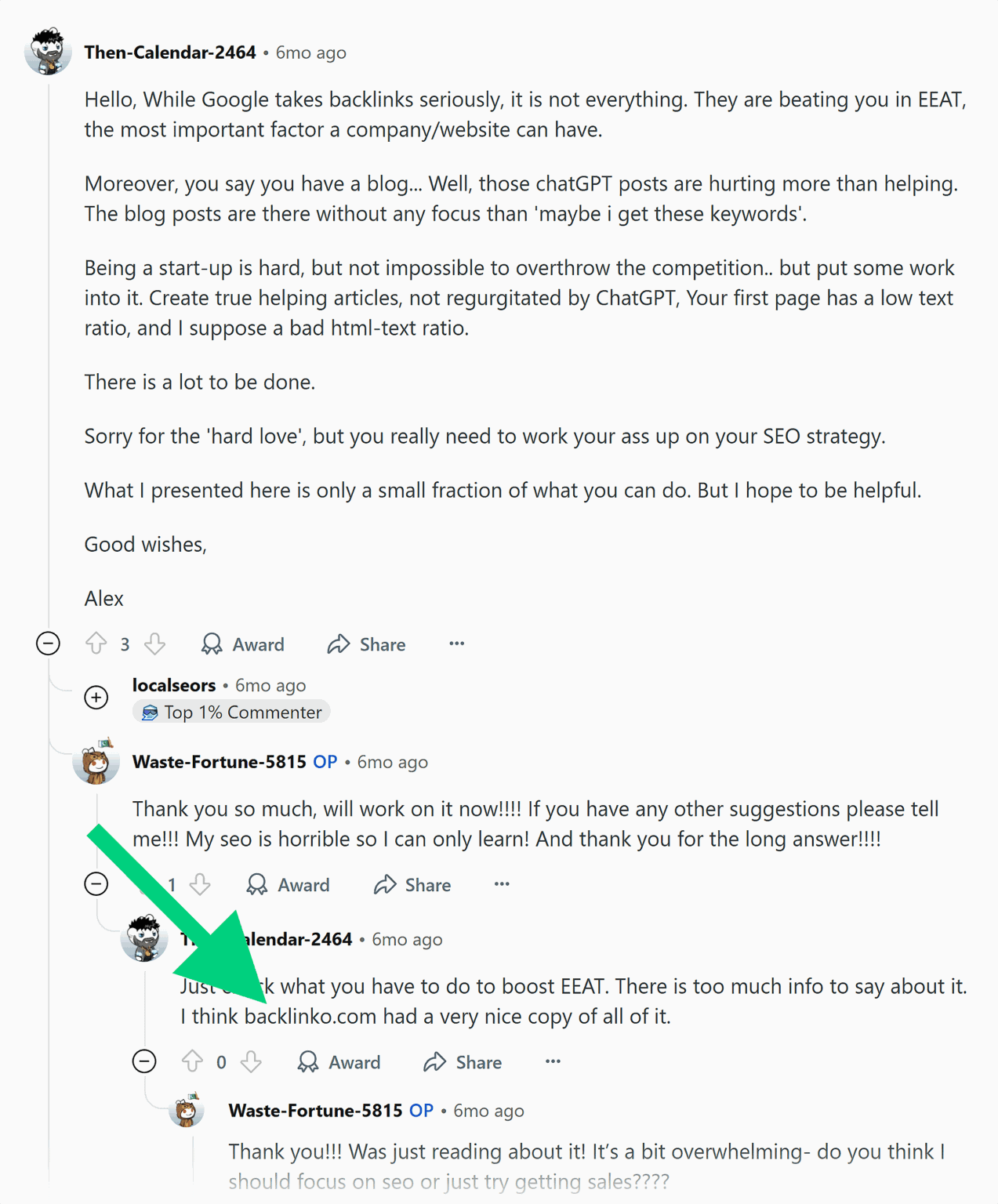

Unlock Hidden Ecommerce Profits: Master SEO Audits in 4 Simple Stages [+ Free Workbook]

Ever wondered why your online store isn’t grabbing the spotlight it deserves on Google —…

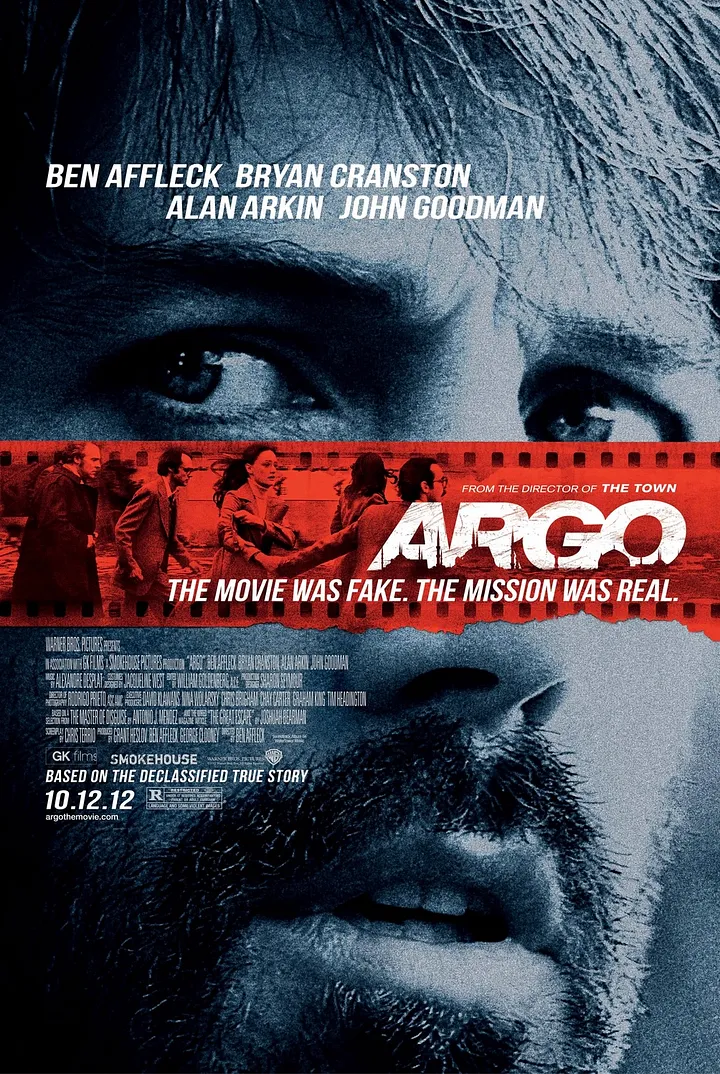

Uncover the Hidden Secrets Behind Every Thrilling Scene in “Argo” (2012)

Ever wonder what it really takes to peel back the layers of a screenplay and…

Unlock the Secret to Instantly Transforming Your WordPress Login Page Logo!

Ever stared at that plain old WordPress login screen and wondered, “Could this be any…

![Unlock Hidden Ecommerce Profits: Master SEO Audits in 4 Simple Stages [+ Free Workbook]](https://writersdepot.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/unlock-hidden-ecommerce-profits-master-seo-audits-in-4-simple-stages-free-workbook-150x150.png)

![Unlock Hidden Ecommerce Profits: Master SEO Audits in 4 Simple Stages [+ Free Workbook]](https://writersdepot.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/unlock-hidden-ecommerce-profits-master-seo-audits-in-4-simple-stages-free-workbook.png)

![Unlock Hidden Ecommerce Profits: Master SEO Audits in 4 Simple Stages [+ Free Workbook]](https://writersdepot.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/unlock-hidden-ecommerce-profits-master-seo-audits-in-4-simple-stages-free-workbook-300x286.png)