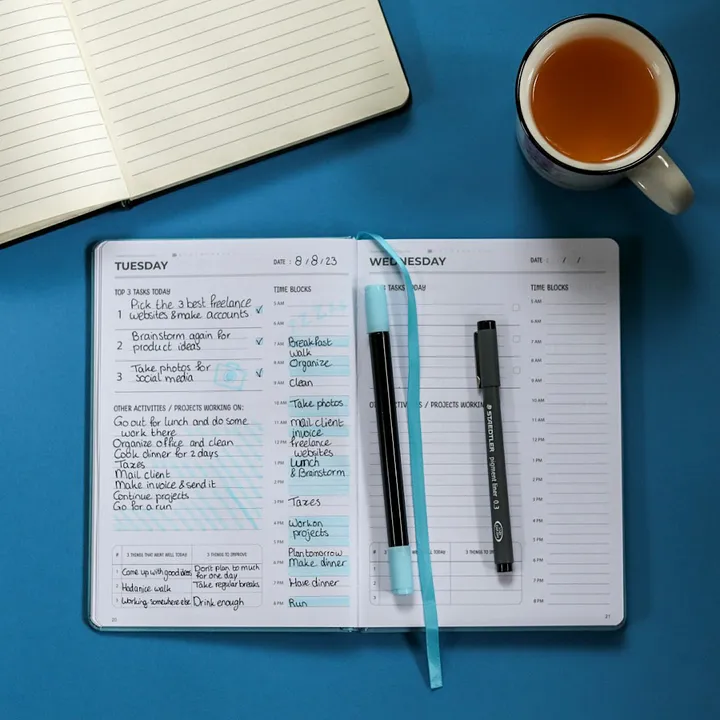

The Surprising Reason You Keep Sabotaging Your Plans — And How to Fix It Fast

Here’s how to get it right.Continue reading on The Writing Cooperative »

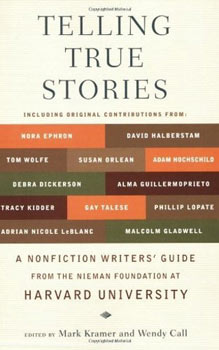

How CCC’s Breakthrough AI Technology Earned a Coveted Spot on KMWorld’s Elite AI 100 List

July 22, 2025 â Danvers, Mass. – CCC (Copyright Clearance Center), a leader in advancing copyright,…

Unveiling the Unexpected Truths Hidden Within “Haircut 1972” – A Poem That Challenges Time and Memory

I was a long haired hippie freak back in the day But the parental units…

Unlock the Secret Power of Haiku: Transform Your Writing in Just Three Lines

Today’s writing exercise comes from my book, 101 Creative Writing Exercises, which takes writers on an…

Unveiling the Secrets of the Enigmatic Purple Flower Tree: A Poem That Will Captivate Your Soul

I didn’t know your name But I knew you were always there Shedding continuous purple…

Unlock Hidden Opportunities: The Secret to Pitching Freelance Gigs That Most Miss

Here’s how to look for undersourced prospects and find their gatekeeperContinue reading on The Writing…

The Hidden Power of Rejection: How Embracing ‘No’ Can Transform Your Life

It can debilitate… motivate… and take a long time to truly grasp its meaning.Continue reading…

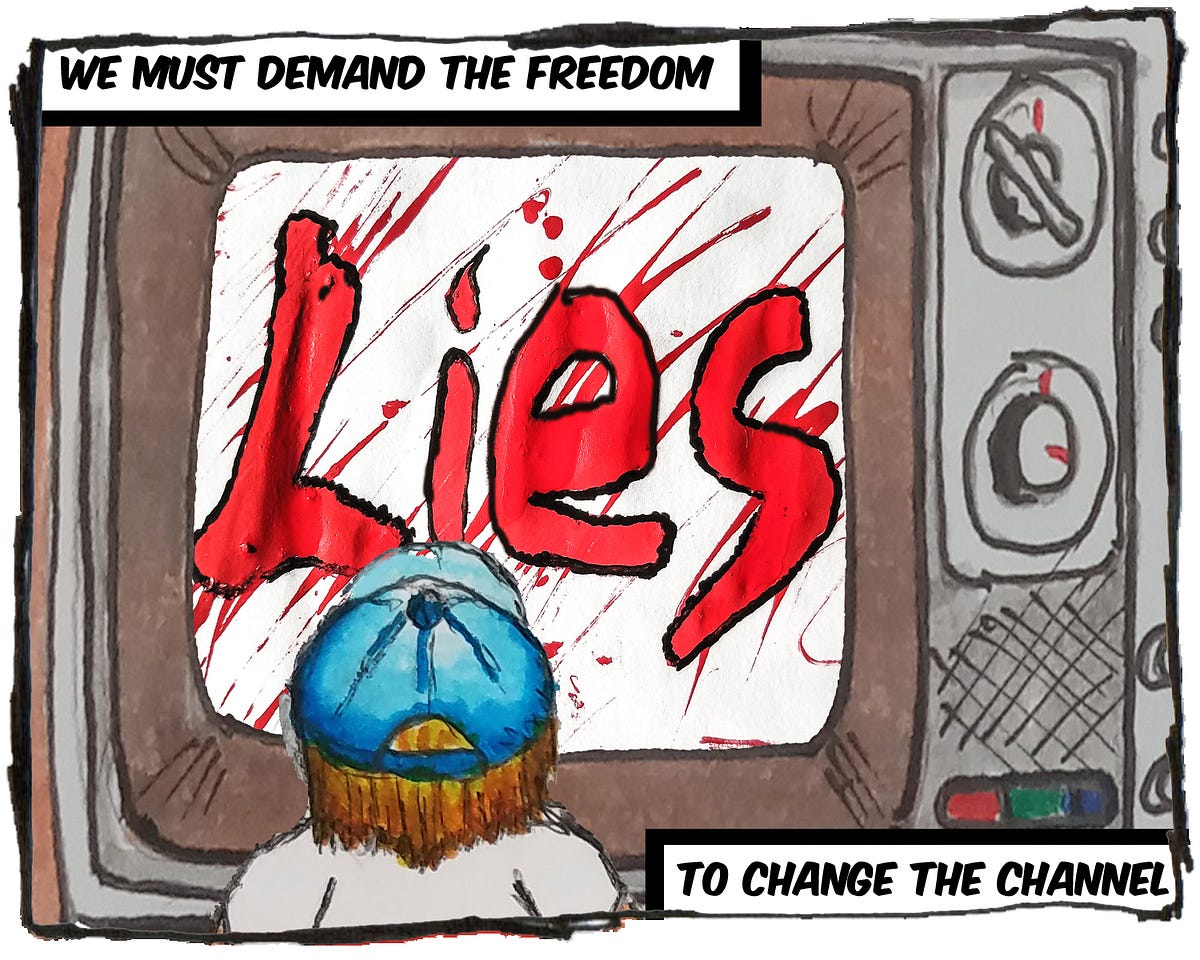

Unmasking Media Manipulation: The Writer’s Secret Weapon Against Ignorance Programming

There’s an astonishing number of brilliant individuals just waiting to share their knowledgeContinue reading on…

The Hidden Secrets Behind Becoming an Unforgettable Author Panelist—And Why Most Fail Miserably

It’s not necessarily about what you knowContinue reading on The Writing Cooperative »

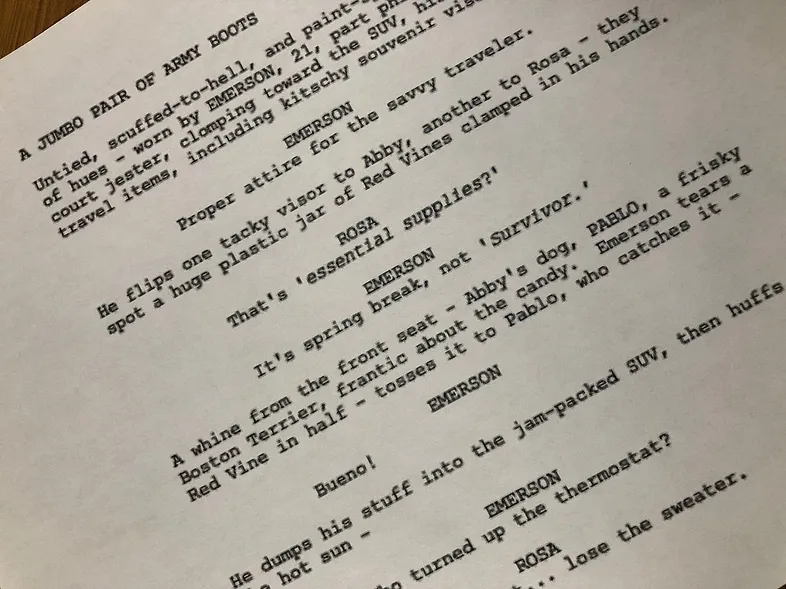

Unveiling the Enigma: G. S. Katz’s Poetic Quest for Truth

Everyone wants the truth Until you give it to them Then they run away From…