From Brian Kim Stefans, Boston Review, December 1, 2001:

Memento, in which the protagonist, lacking any ability to create new memories, has to tattoo his body with messages in order to maintain any sense of life’s continuity. Hejinian seems to find pleasure, if not an untapped resource, in the ability to lose one’s direction, as the objects of her thought—”my car,” “my convictions,” “my style”—do not easily persist through time, but are willed forward by artful decisions. These decisions put the individual at the center of one’s own world; they constitute the struggle to maintain engagement with the “everyday,” to understand every second as moments of judgment: chance leading to choice. The persistence of matter may be untroubled in Hejinian, but the persistence of mind about matter is always an issue.

There is also something spiritual—in the tradition of Buddhist poetics as explored by many West Coast writers, most notably Philip Whalen—in Hejinian’s ideas, as when she writes in her introduction to Language of Inquiry: “Poetry, therefore, takes as its premise that language is a medium for experiencing experience.” These sorts of doubling of words—”If Written is Writing,” is the title of another essay—suggest a deep retreat behind one’s mind in order to get perspective on how knowing actually works. Skepticism, the elite perspective of a hard-earned Western rationality, is matched with bodily discipline and thus questions all absolutes, including the authority of the skeptical mind itself, only finding satisfaction or assurance—further calls for discipline—when observing the mind in action. Consequently, this self-reflection takes on a social dimension—the heart of all of Hejinian’s thinking—as one is, deep in the mind, a step further away from the socialization implicit in the “titillating public display” of hyper-mediating capitalist culture. Hence, this practice of thinkingthrough one’s singularity, not in fear of it, is both aesthetic and ethical in nature.

Even Hejinian’s essays that seem to be about the “social”—political ideas, relations of poetic form to social meanings, or feminist concerns—all hinge on the fact of the mind. In her 1995 essay “Barbarism” she re-reads Adorno’s famous statement: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is an act of barbarism.” The standard interpretation is that Adorno was declaring culture impossible in a world whose history had proven disastrous—guided by acts of the collective will in which such forms as the “lyric,” now fallen from its “folk” status, cut off the individual from society. Hejinian suggests that his statement “can be interpreted in another sense, not as a condemnation of the attempt ‘after Auschwitz’ to write poetry, but…as a challenge and behest to do so.” The poet, however, endeavors “not to speak the same language as Auschwitz” but instead to speak a language that is doubled, as incoherent babbling to the masters, poetry to the rest. >>>

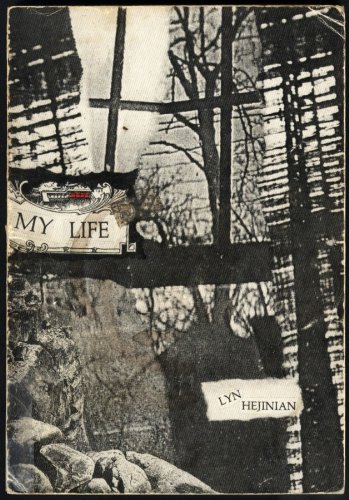

We mourn the passing of Lyn Hejinian, celebrated poet, author of My Life, and editor of The Best American Poetry 2004.

https://www.bestamericanpoetry.com/pages/editors/?id=2004

https://www.chicagotribune.com/2013/03/23/review-my-life-and-my-life-in-the-nineties-by-lyn-hejinian-2/

Go to Source

Author: The Best American Poetry