Unveiling the Silent Struggle: G. S. Katz’s Poetic Journey Through Isolation

Ever found yourself lurking on the edges—neither fully in nor completely out—grappling with the fine…

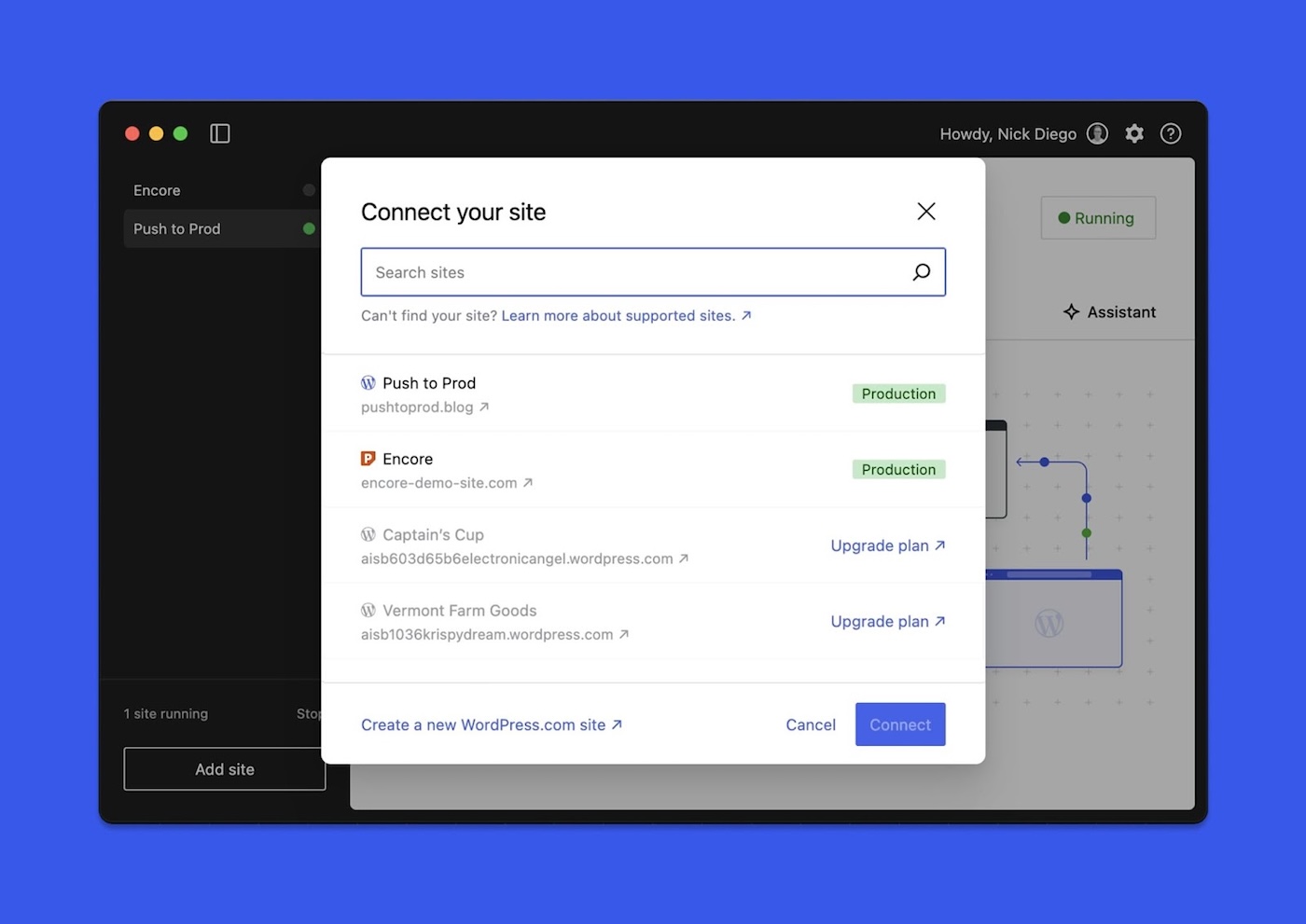

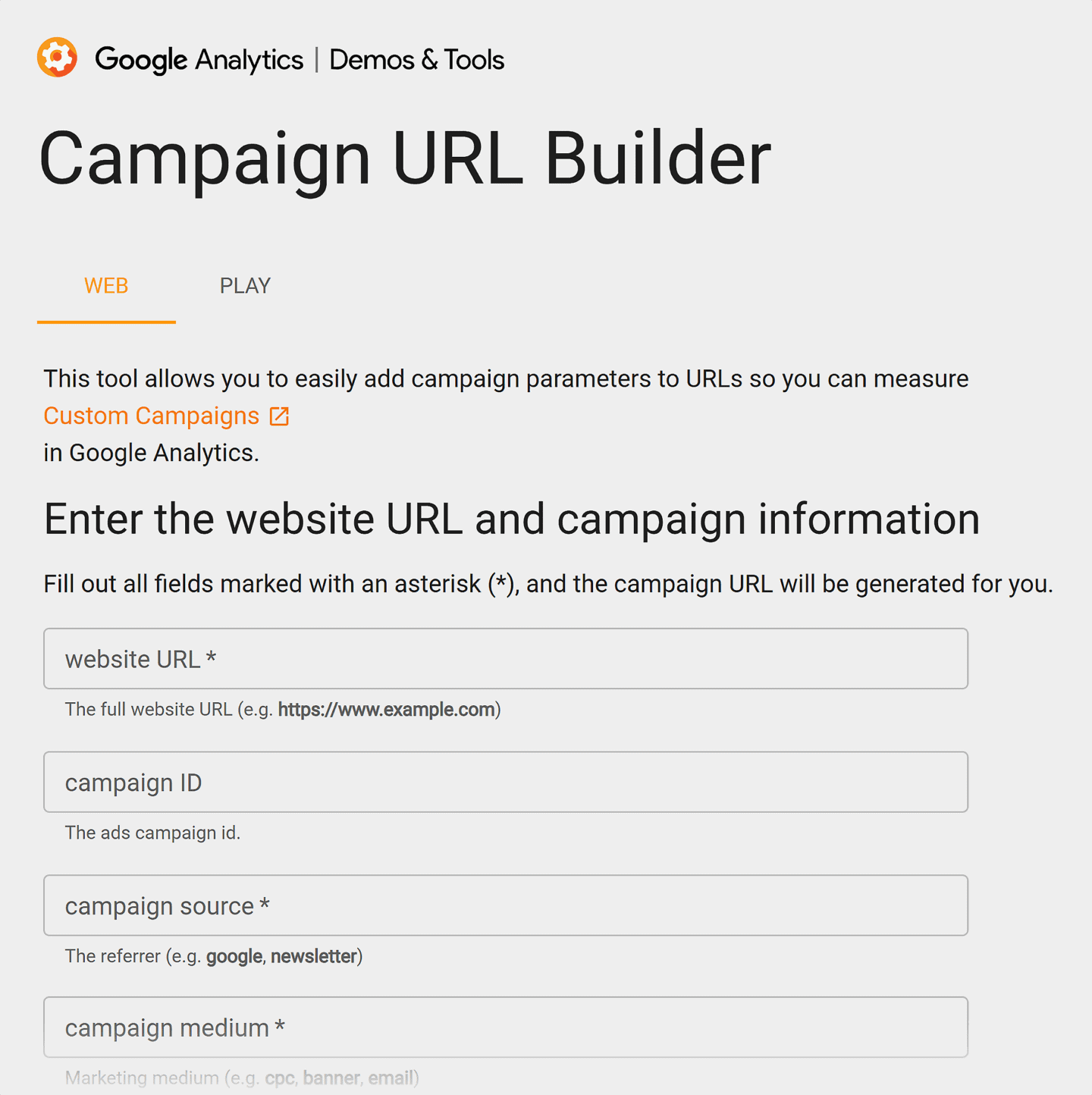

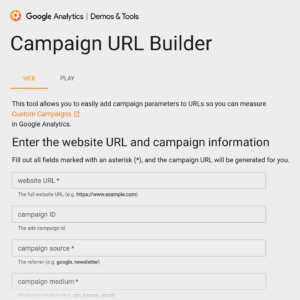

Unlocking the Secret Code: How LLM Seeding Could Make Your Work Unstoppably Popular with AI Models

Ever wondered why your website traffic is taking a mysterious nosedive, even though you’re still…

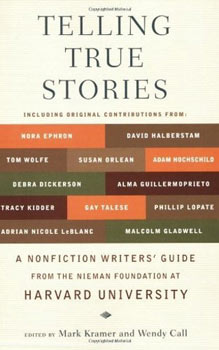

Unlock Hidden Stories: Rebecca Danzenbaker Reveals the Secret to Writing That Captivates Instantly

Ever wonder what it feels like when life’s usual script gets flipped upside down—and suddenly,…

Unlocking the Secrets Within: Navigating the Enigmatic Hall of Mirrors in Your Memoir

Ever wondered what it truly means to dive into your past and come face-to-face with…

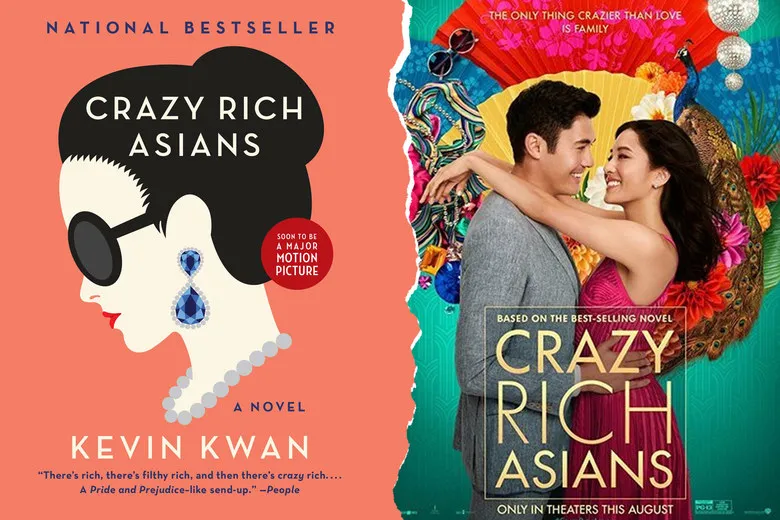

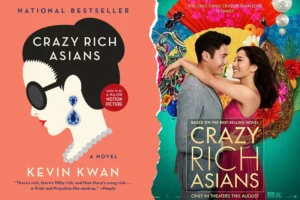

Unveiling Hidden Details: A Scene-by-Scene Dissection of "Crazy Rich Asians" That Will Change How You See the Film

Ever wondered what it truly means to “break down a screenplay”—not just by scene, but…

Unveiling Hidden Truths: The Provocative Confession in G. S. Katz’s Poem

Ever wonder what it’s like to reveal a secret passion after over two decades of…

Unraveling Shadows: The Haunting Truth Behind “Fading…” by Joanne J.

Isn’t it curious how silence can sometimes whisper louder than words ever could? Here, in…

Unlock the Secret 6-Step Formula to Creating a Customer-Focused Content Strategy That Converts

Ever feel like your content is shouting into the void—pages and posts thrown out there…

The Hidden Truth About Newsletters That No One Wants You to Know

Ever find yourself opening a newsletter, expecting a treasure trove of writing wisdom, only to…

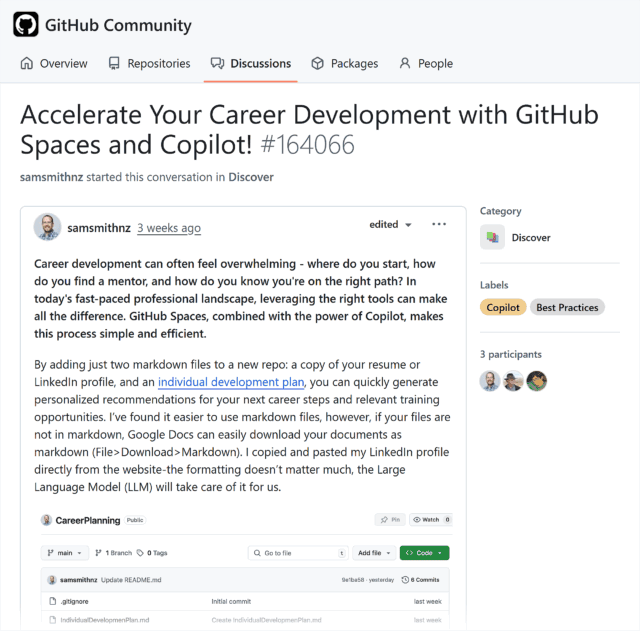

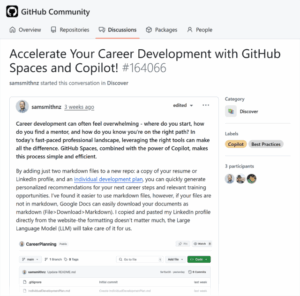

Brian Dean’s 2025 Blueprint: The Surprising Backlinko Relaunch That Could Change SEO Forever

Imagine if Brian Dean had to start Backlinko today—in a world where Google isn’t the…