Unlocking the Secrets Within: Navigating the Enigmatic Hall of Mirrors in Your Memoir

Ever wondered what it truly means to dive into your past and come face-to-face with…

Unveiling Hidden Truths: The Provocative Confession in G. S. Katz’s Poem

Ever wonder what it’s like to reveal a secret passion after over two decades of…

Unraveling Shadows: The Haunting Truth Behind “Fading…” by Joanne J.

Isn’t it curious how silence can sometimes whisper louder than words ever could? Here, in…

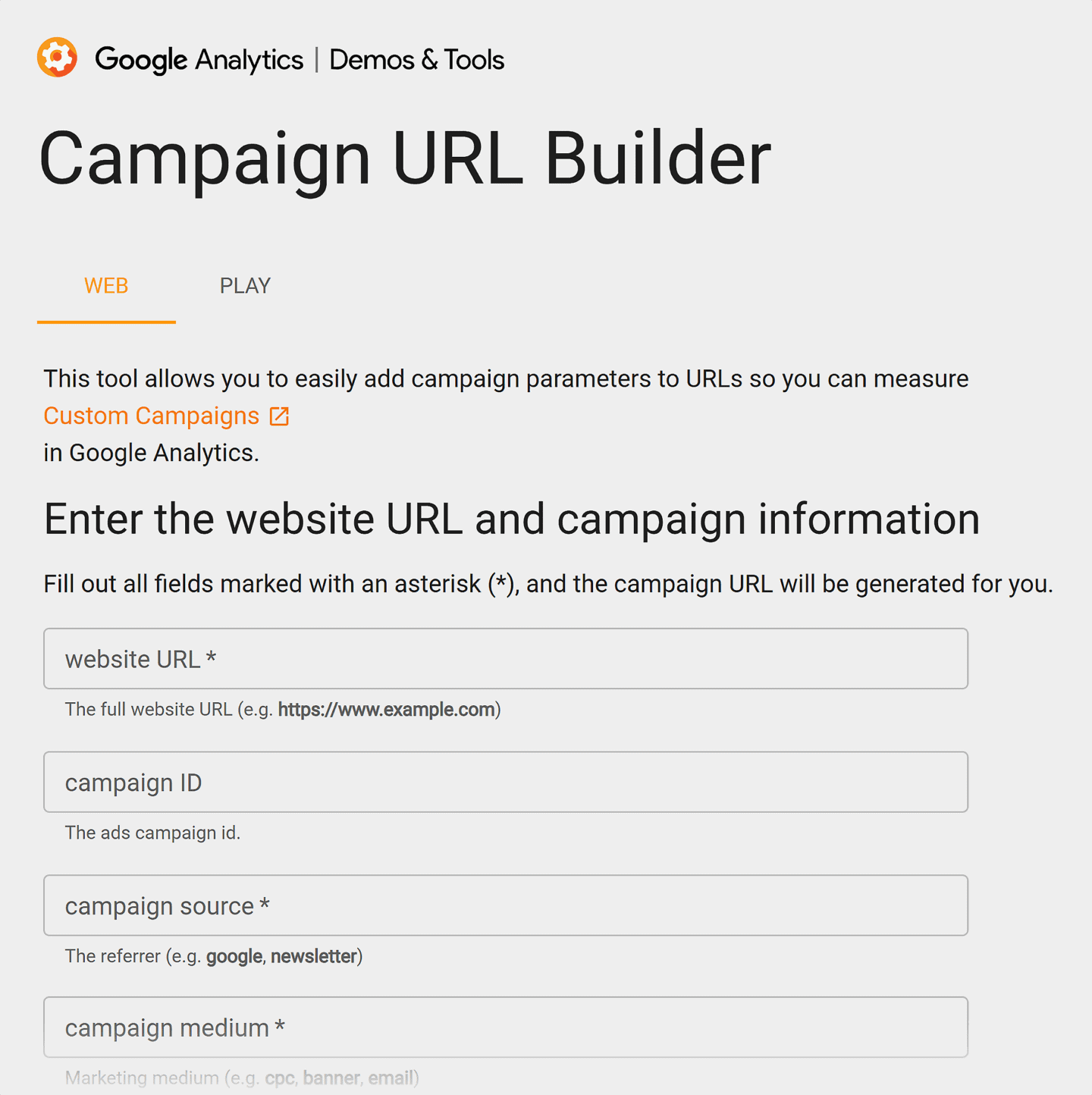

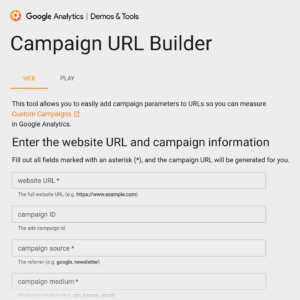

Unlock the Secret 6-Step Formula to Creating a Customer-Focused Content Strategy That Converts

Ever feel like your content is shouting into the void—pages and posts thrown out there…

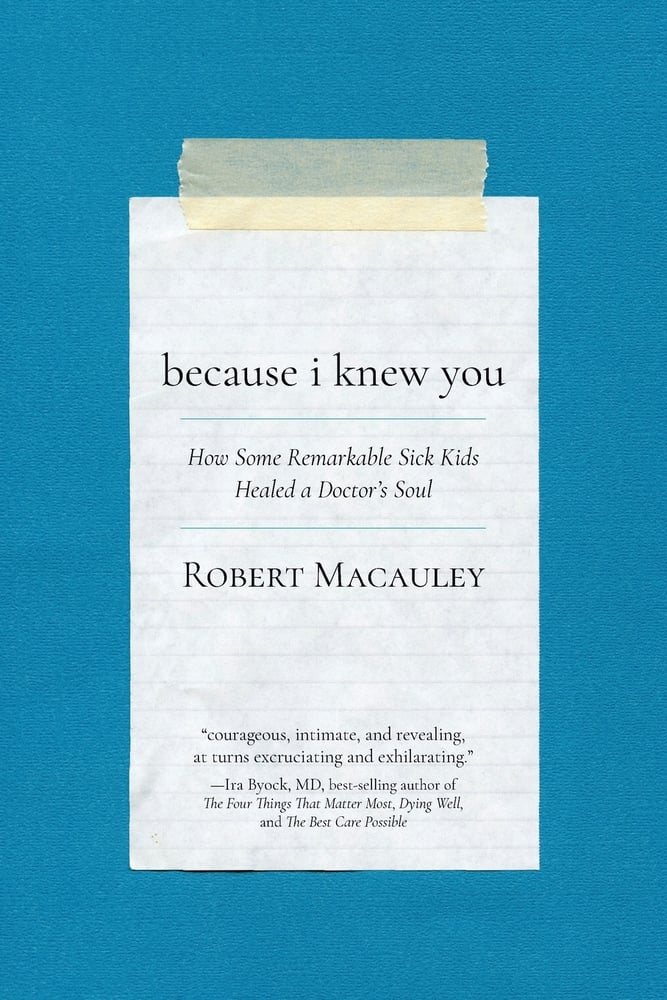

The Hidden Truth About Newsletters That No One Wants You to Know

Ever find yourself opening a newsletter, expecting a treasure trove of writing wisdom, only to…

Brian Dean’s 2025 Blueprint: The Surprising Backlinko Relaunch That Could Change SEO Forever

Imagine if Brian Dean had to start Backlinko today—in a world where Google isn’t the…

Unlocking the Hidden Secrets Behind Provoking Real Change – What No One Tells You

Ever had that sinking feeling when you step up to rally your team, only to…

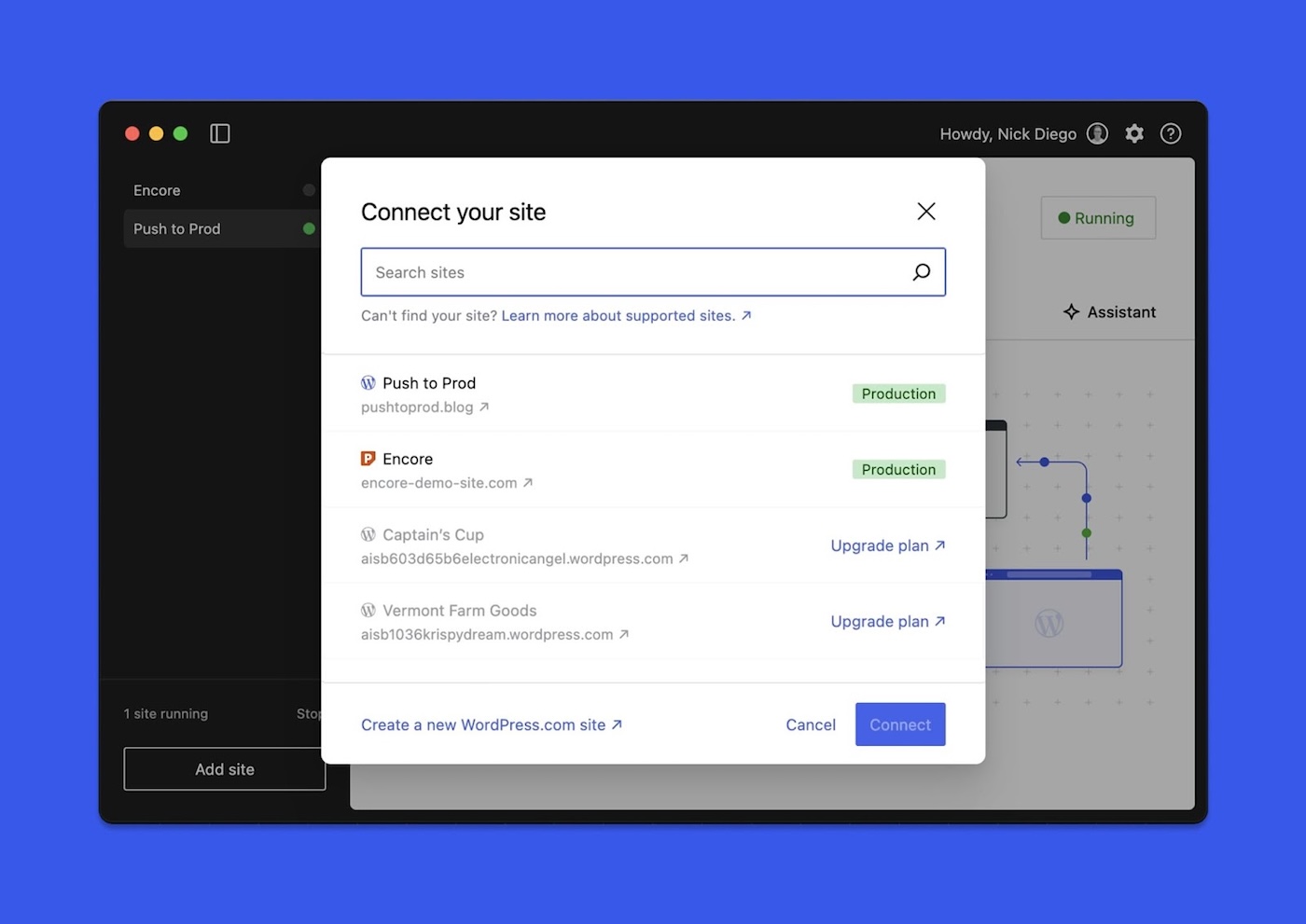

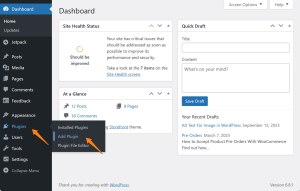

Unlock the Hidden Power of Schema Markup on Your WordPress Site – What You’re Missing Could Skyrocket Your SEO!

Ever wonder why some websites shimmer with star ratings, glowing reviews, and tempting product prices…

Unlock the Secrets Hidden Between the Lines: Master the Art of Reading Poetry Like Never Before

Ever catch yourself instantly obsessed with a new song—playing it on repeat, memorizing every lyric,…

Unveiling Hidden Whispers: Bruce Louis Dodson’s Enigmatic Nepalese Journey in Verse

Have you ever paused to wonder what it feels like when the heavens weep in…