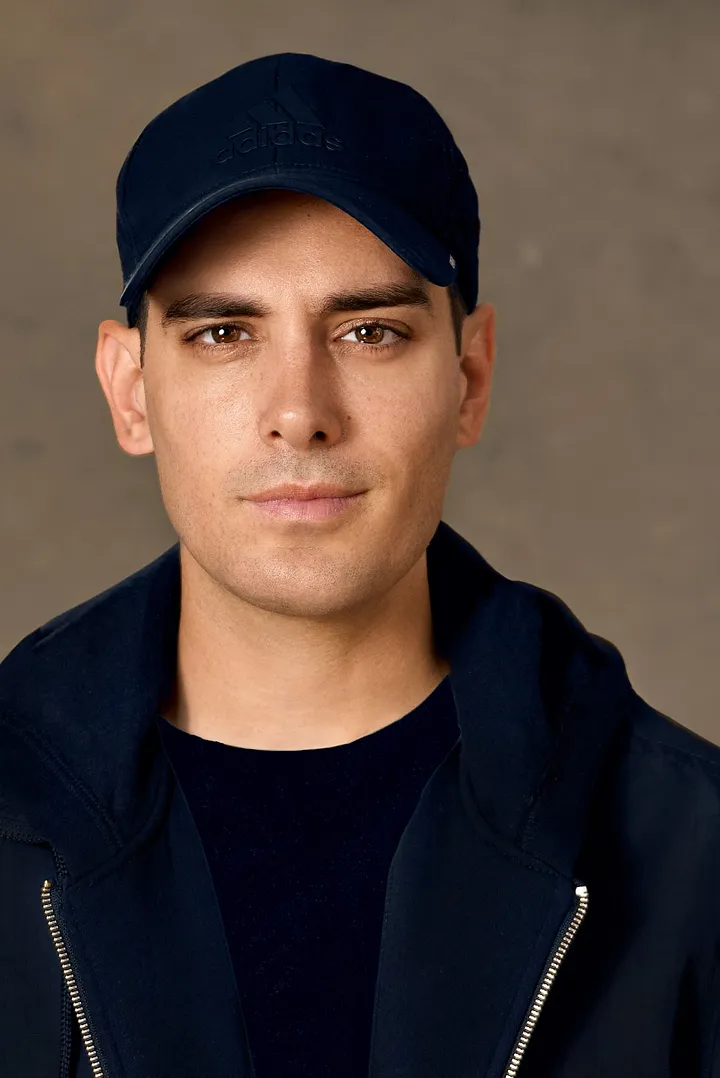

Unlock the Hidden Secrets Behind Justin Colón’s Revolutionary Writing Method—Are You Ready to Transform Your Words?

Ever wonder how a kitchen table, a steady stream of coffee, and a dash of…

Unlock the Secret to a Captivating Writer’s Voice That Readers Can’t Ignore

Ever wondered what people really mean when they talk about a writer’s "voice"? It’s the…

Discover the Hidden Depths in G. S. Katz’s Brief but Powerful Poem “Short and Sweet”

Isn’t it fascinating how some of the richest treasures in life aren’t minted coins or…

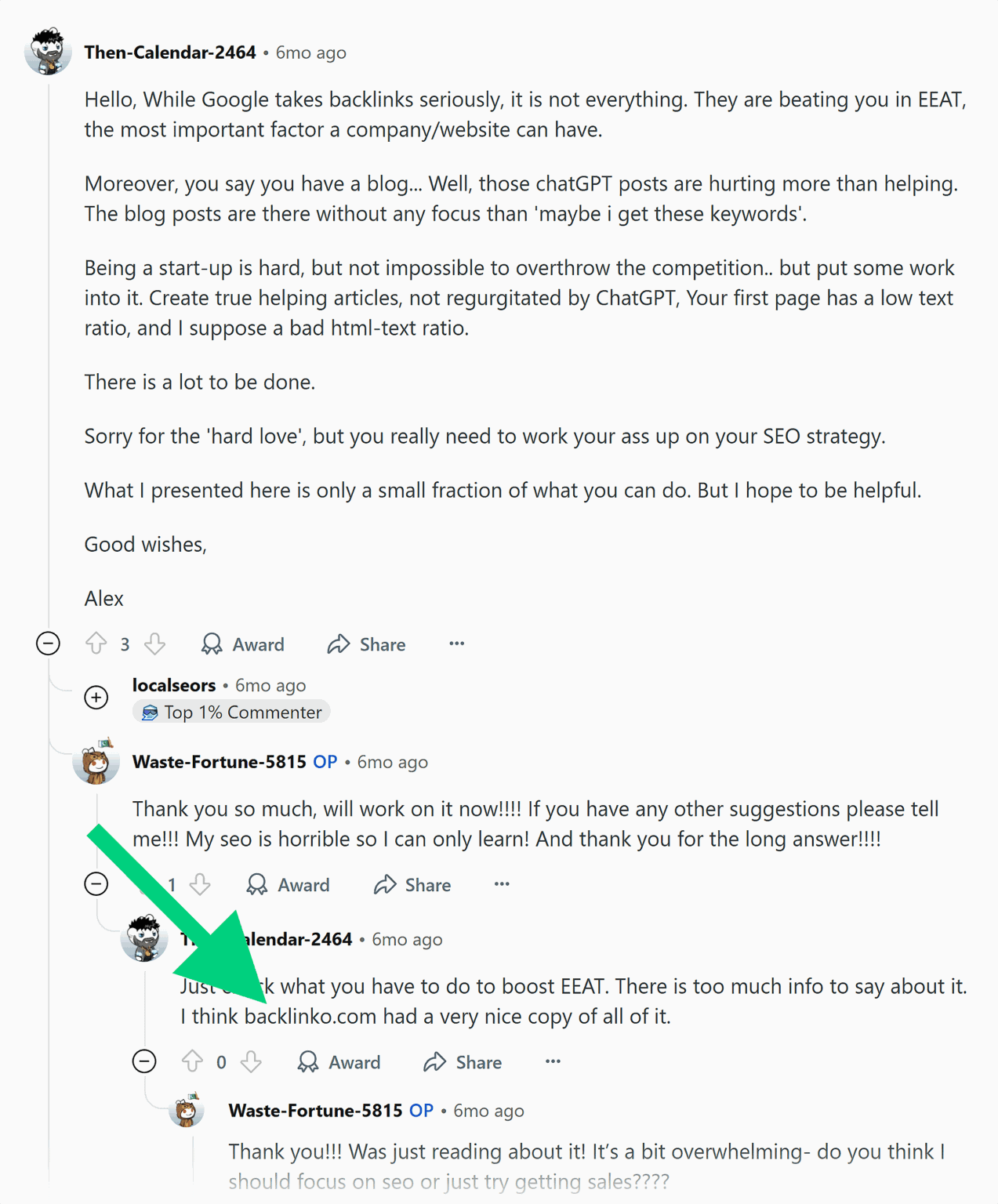

Unlock the Secret Strategy Behind Generative Engine Optimization That’s Revolutionizing AI Search Forever

Ever wondered why your brand might suddenly become the wallflower at the AI-generated dance party…

Unveiling Hidden Depths: G. S. Katz’s Poetic Tribute to Raymond Carver That Will Change How You See His Work

Have you ever wondered how a master wordsmith like Raymond Carver would twist today’s turmoil…

Unlocking the Mystery: How Nonsensical Dreams Secretly Ignite Your Best Writing Ideas

Ever woken up from a dream that felt less like your own and more like…

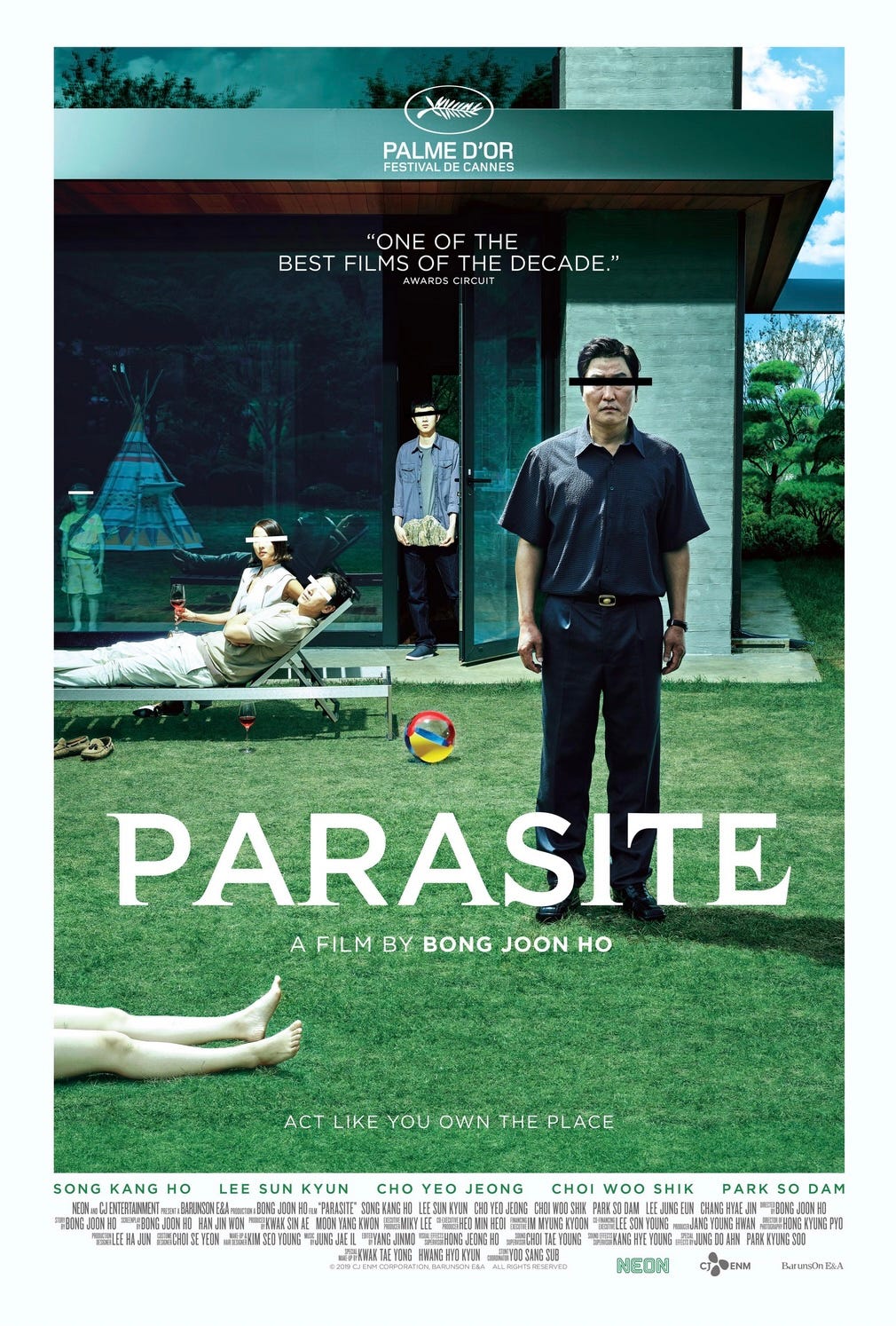

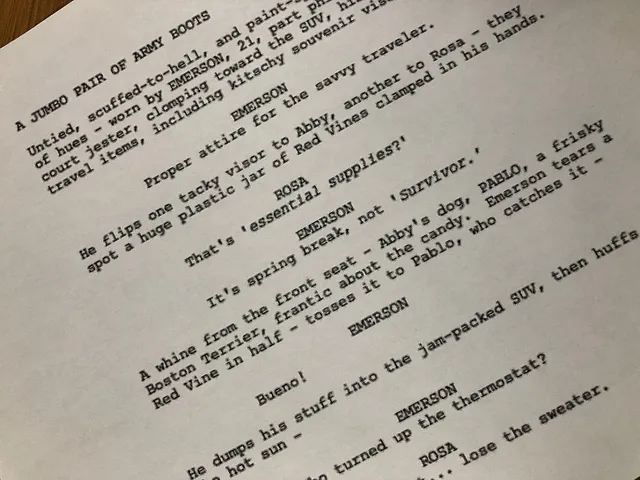

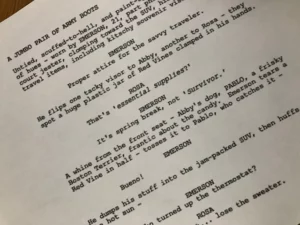

Unlocking the Secrets of Screenwriting: Allan Durand’s Surprising Formula for Success

Ever wonder what it takes to write a screenplay that doesn’t just get finished but…

Unlock the Hidden Creativity Secrets Top Thought Leaders Swear By—Prepare to Be Surprised!

Ever notice how diving deep into a subject—like the hypnotic rhythms of African drumming or…

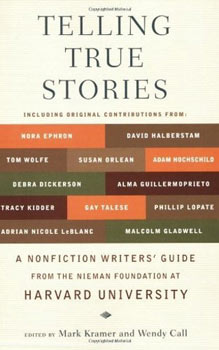

Unlock the Secrets Behind Crafting True Stories That Captivate and Inspire

Ever wonder how you can spin the truth and still keep your readers hooked? Welcome…

Unveiling the Hidden Colors: Kathy Anderson’s Poem That Transforms Life’s Ordinary Moments

Ever notice how the simplest shades can hold the wildest stories? I mean, take the…