Discover the Hidden Depths in G. S. Katz’s Brief but Powerful Poem “Short and Sweet”

Isn’t it fascinating how some of the richest treasures in life aren’t minted coins or…

Unveiling Hidden Depths: G. S. Katz’s Poetic Tribute to Raymond Carver That Will Change How You See His Work

Have you ever wondered how a master wordsmith like Raymond Carver would twist today’s turmoil…

Unlocking the Mystery: How Nonsensical Dreams Secretly Ignite Your Best Writing Ideas

Ever woken up from a dream that felt less like your own and more like…

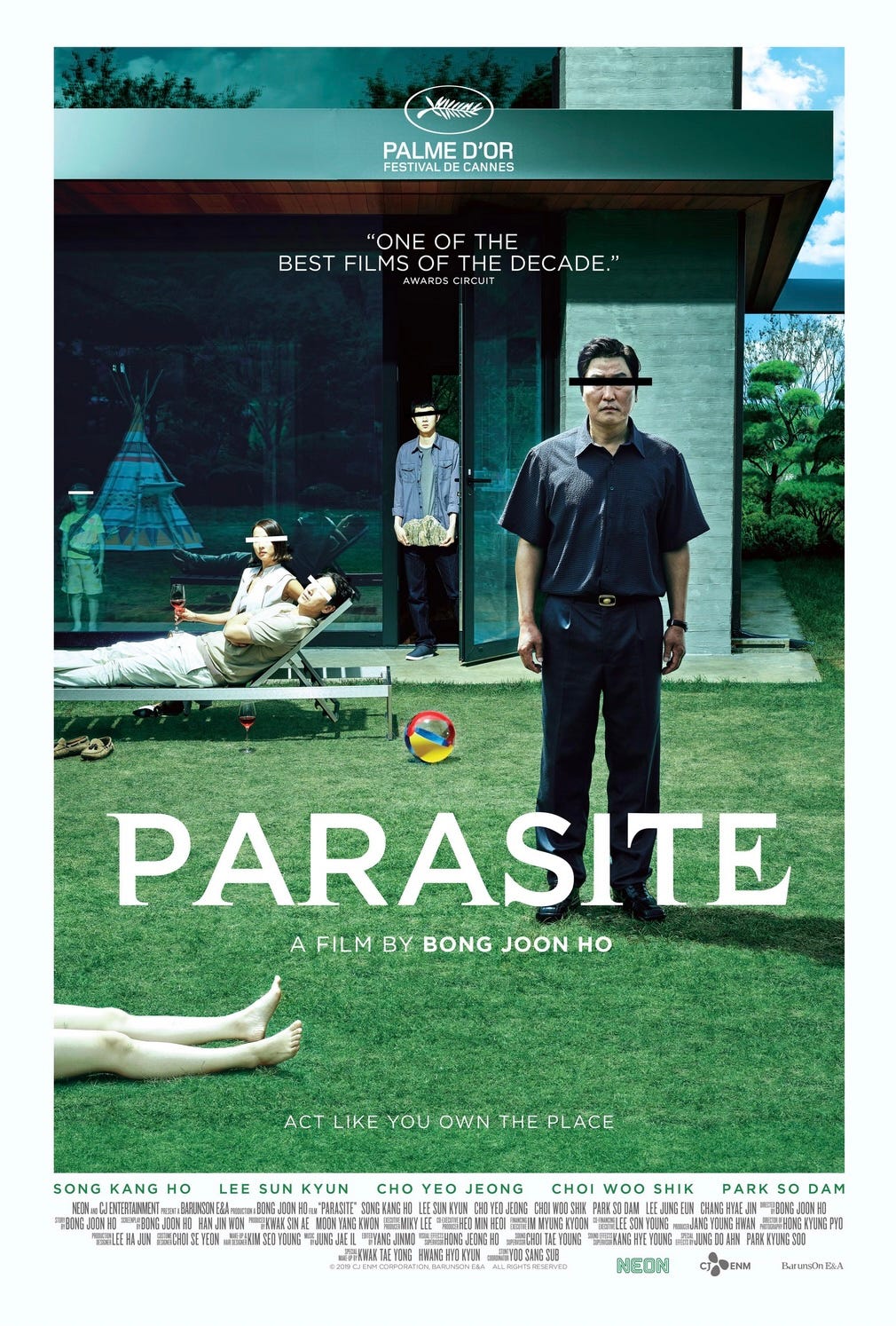

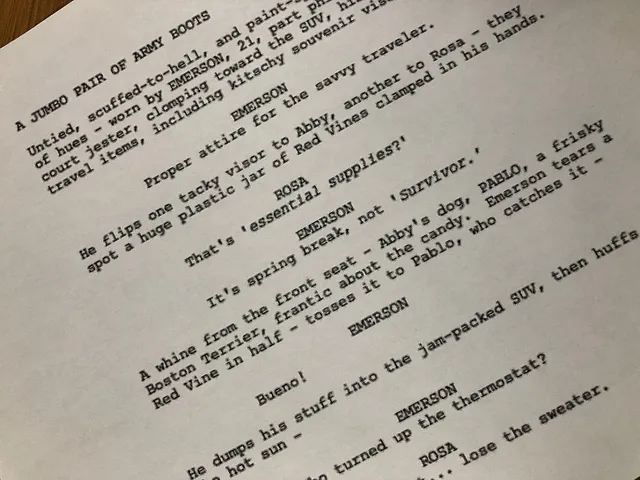

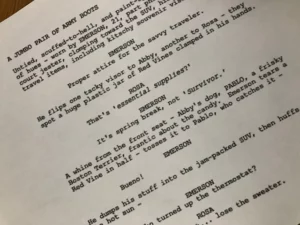

Unlocking the Secrets of Screenwriting: Allan Durand’s Surprising Formula for Success

Ever wonder what it takes to write a screenplay that doesn’t just get finished but…

Unlock the Hidden Creativity Secrets Top Thought Leaders Swear By—Prepare to Be Surprised!

Ever notice how diving deep into a subject—like the hypnotic rhythms of African drumming or…

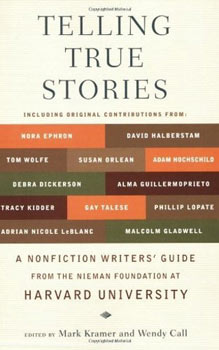

Unlock the Secrets Behind Crafting True Stories That Captivate and Inspire

Ever wonder how you can spin the truth and still keep your readers hooked? Welcome…

Unveiling the Hidden Colors: Kathy Anderson’s Poem That Transforms Life’s Ordinary Moments

Ever notice how the simplest shades can hold the wildest stories? I mean, take the…

Unlock the Secret Power of the 4 Cs—Why Mastering Them Could Change How the World Reads You Forever

Ever find yourself tangled up in words, wondering why expressing a simple thought feels like…

The Hidden Struggle of Living Abroad: How Distance Turns Books into Forbidden Treasures

Ever found yourself craving the feel of a real book in your hands, rather than…

The Unexpected Melody That Healed a Lifetime of Heartache—Discover the Robin’s Secret Song

Have you ever paused mid-step, caught off guard by the simple, soulful trill of a…