Unearthing Haunting Secrets: Erica Stern’s Frontier Blends Memoir and Ghost Story in Chilling Harmony

Ever wonder what it truly means to tread into the unknown territory of motherhood—beyond the…

Unveiling the Secrets Behind “Double OhOh”: A Poetic Journey by Bob Eager

Ever stumbled over words only to realize that repeating a careless remark turns a minor…

When Praise Feels Like a Verdict: The Haunting Truth Behind “Good, but Not Good Enough”

Ever find yourself stuck in that maddening spot where you’re told you’re “good but not…

Unveiling Miracles: How Remarkable Sick Kids Restored a Doctor’s Lost Faith

How do you write about the unthinkable—children facing the end of their young lives—without drowning…

Why I Couldn’t Stop Chasing Gold Stars—Even When I Thought I Was Finished

Ever notice how the chase for gold stars can sneak back into your life when…

Unveiling Triumph: Naduni’s Poem That Redefines Victory Like Never Before

Have you ever felt a presence so profound it blurs the lines between reality and…

Exclusive Interview: Jennifer Crystal Reveals the Shocking Inspiration Behind One Tick Stopped the Clock

Ever wondered how a single tick bite can spiral into a 13-year odyssey of illness,…

Master the Art of Submitting: The Secret to Thriving as a Writer Without Burning Out

Ever felt like you’ve just whipped up the most spectacular dish imaginable—only to find yourself…

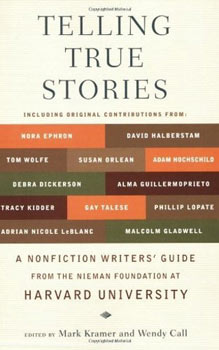

The Surprising Playbook Footballers Use to Master Writing—And How You Can Too

Ever watch a footballer tear it up on the pitch and wonder how in the…

Step Inside Shannen Wrass’s World: A Poem That Reveals Hidden Truths You Won’t Forget

Ever found yourself staring at the edge of an empty tear duct, wondering if sorrow…