The Surprising Truth I Discovered Too Late About Publishing My First Book

Ever wonder why everything in the publishing world seems to move slower than molasses on…

Unveiling the Enigma: Shelley Nutting’s “Shadow Play” Reveals Secrets in the Dark

Ever caught yourself wondering how an ordinary moment—like a chilly autumn evening on a hillside—can…

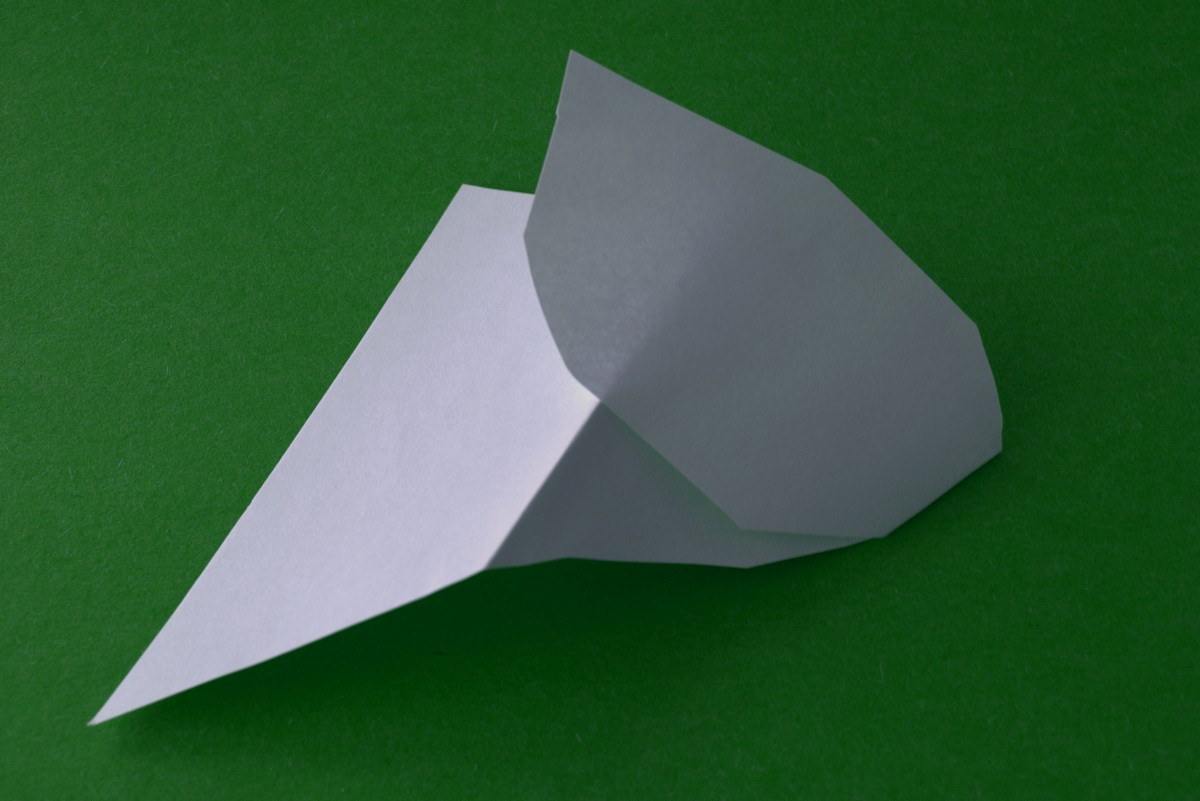

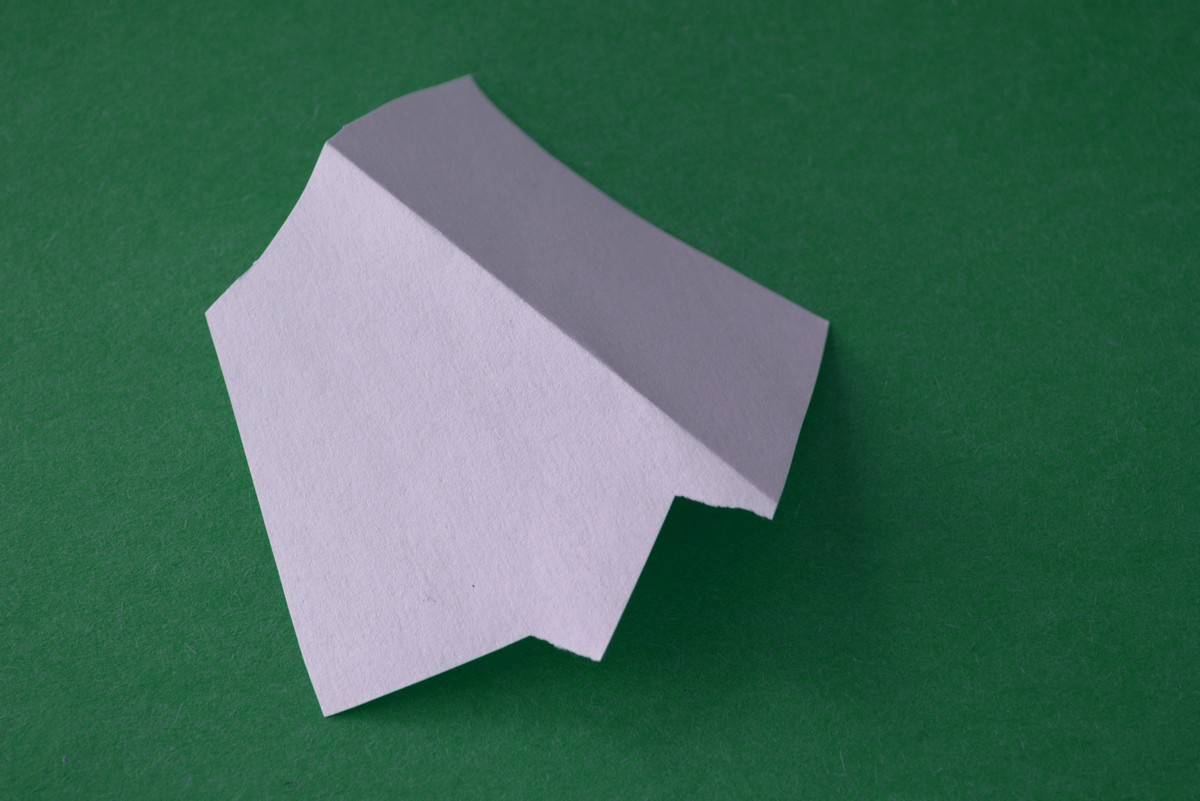

Unlock the Secret Advantage: Why Custom Writing Mockups Crush Traditional Samples Every Time

Ever find yourself stuck in the endless loop of sending generic writing samples that vanish…

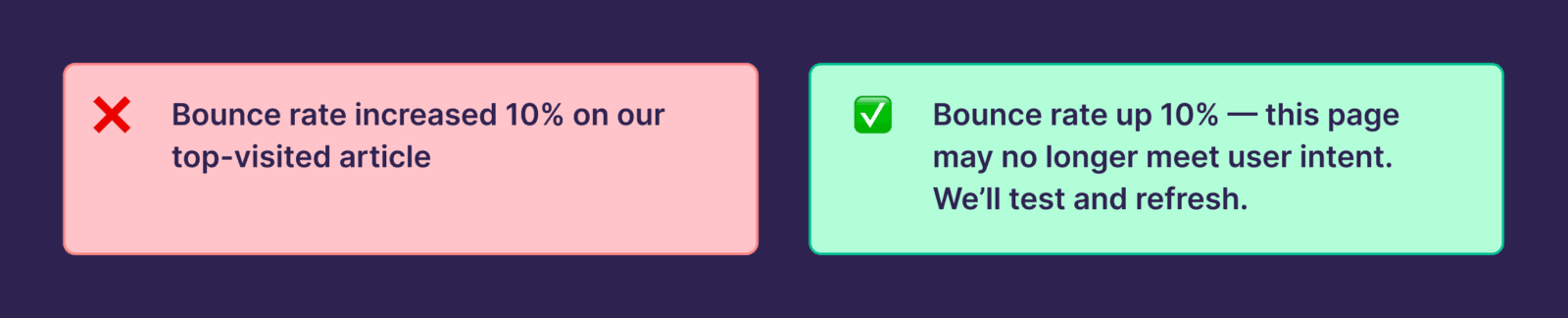

Unlock the Secret Editing Weapon You’re Overlooking: How a Simple Calendar Can Transform Your Workflow

Ever felt like your editing tools are either too brutal or just plain useless? What…

When the Healing Stops: Facing a World Without Doctors or Medicine

Ever wondered what happens when society hits a brick wall and suddenly, there’s no doctor…

Unveiling the Silent Gaze: The Haunting Mystery Within G. S. Katz’s “Watching You”

Isn’t there something utterly mesmerizing about those quiet morning moments when someone you adore stirs…

Unveiling the Dark Secrets Behind Malice in Wonderland: What Alvin Wander Didn’t Tell You

Ever wonder what it feels like to be wrapped inside a web of secrets, conspiracies,…

Unveiling Desire: The Seductive Secrets Hidden Within G. S. Katz’s Poem “Lust”

Is lust merely a fleeting impulse, or is it the very compass that crafts our…

Unveiling the Secrets: How Thomas Berry Transformed Words into Awards and Millions of Pages Written

Ever wonder how some authors manage to pen seven books, snag literary awards, and still…

Unveiling the Mind-Bending Secrets Behind Every Scene of “Everything Everywhere All At Once”

Ever sat down with a screenplay and wondered—how on earth do you unpack all those…