If you’ve ever wandered through the bustling alleys of Reddit, Facebook, or Twitter, you’ve surely stumbled upon heated discussions about the ins and outs of screenwriting. It’s like a treasure trove of opinions, all muddled in a delightful debate over rulebooks that were penned during the golden age of the 1990s when spec scripts were selling like warm pastries. Among those time-tested nuggets of wisdom, one phrase stands out like a sore thumb: “Never direct the camera— that’s the director’s gig.” Oh, the irony! While this advice holds truth, it often comes cloaked in vague interpretation for budding screenwriters today… So, how do we navigate these murky waters? Let’s peel back the layers on camera directions and explore whether they belong in your screenplay—or if you should let the directors do the heavy lifting. Here’s a little hint: It depends! LEARN MORE

Visit any Reddit, Facebook, or Twitter screenwriting thread, and you’ll witness much debate when it comes to any form of screenwriting advice offered or questioned. Some of the screenwriting “rules” date back to the screenwriting boom of the 1990s when spec script sales were at an all-time high—and when screenwriting books were all the rage.

Perhaps the most lasting advice from back in the day is:

Never direct the camera by writing specific camera directions. That’s the director’s job.

There is a lot of truth to that statement.

However, the details and meaning have been lost for the up-and-coming generation of screenwriters — and those that improperly offer overly generalized versions of that advice.

Here we briefly tackle the subject of camera directions and whether or not you should include them in your screenplays. Here’s a hint at what is to come: It depends.

What Is a “Camera Direction” in Screenwriting Terms?

A camera direction is found in a screenplay’s scene description (the action section).

Scene description is a screenwriter’s key to the success of their screenplay, specifically from the standpoint of how easy it is for the reader to truly experience your story in a cinematic fashion. You want the reader to be able to decipher the visuals you are describing in your scene description as quickly as possible—as if they were reels of film flashing before their eyes.

Sadly, most novice screenwriters fail to understand the importance of writing cinematically. Instead, they often fall into the trap of directing the camera.

It’s not your job as a screenwriter to dictate where the camera is all of the time. That comes into play when a director and cinematographer are brought on board to translate your screenplay into moving pictures.

Camera direction is where the scene description and sluglines dictate how, when, and where the camera moves. For example:

- The camera DOLLIES LEFT as…

- The camera TILTS UP and PANS RIGHT…

- MEDIUM SHOT of…

These are the types of camera directions that the old-school screenwriting “rule” points to most—the specific directing of the camera when it comes to camera placements, camera angles, and camera movement.

And that “rule” is on point, and screenwriters shouldn’t be doing that.

The bad habit usually stemmed from screenwriters reading older screenplays written by auteurs. Auteurs are people who both write and direct their own screenplays. Because they are also the director, the practice of including camera directions is purposeful because they are creating a more specific blueprint for a film story that will be told through their vision.

Film is a director’s medium.

When a screenwriter is writing a script that they are likely not going to direct, they should refrain from including specific camera directions.

When the script is handed over to a director, the collaborative relationship shifts as they interpret that screenplay through their director’s eyes. Thus, specific camera directions like camera placements, camera angles, and camera movements are a waste of very valuable screenplay page real estate. Not to mention the fact that the director is going to shoot it however they want—camera direction or no camera direction within the script.

However, the contemporary definition of camera directions in a screenplay has become somewhat over-generalized. There are times when screenwriters can (and should be) showcasing certain camera elements.

What Types of Camera Directions Can Screenwriters Use?

Lost within the over-generalized “rule” of no camera directions are terms and practices that are either allowed/tolerated or necessary to write a cinematic screenplay.

We See…

There is a lot of debate online about using this phrase in your scene description—and most of the people who decry the practice as a sign of an amateur or screenwriting rule-breaker don’t really know what they’re talking about. Or, as in most cases, they are, again, over-generalizing.

The use of “we see” dates back to the earliest days of contemporary screenwriting. The phrase was often used in the pitching process, putting the pitcher—and those being pitched to—into the lens of the camera. It was a way of connecting to whoever you were pitching a story to, allowing them to see your vision through your cinematic description.

This carried over into screenplays and is still used by celebrated and successful screenwriters. Today, it’s a stylistic choice—a screenwriting vernacular, if you will. You can often format it like this:

An endless country road stretches out to the horizon. We see a car driving fast down the road.

Using “we see” is not a camera direction. And, no, it’s not frowned upon or used as an excuse to toss the screenplay away.

No, you don’t want to use it in every other line of scene description. That would be a type of repetitive verse that would grate on even the most open-minded industry insider reading your script. But it’s not a condemned phrase by any means.

Check out this example from Jennifer’s Body:

‘Jennifer’s Body’ (2009)

POV

POV stands for Point Of View. It’s usually featured in a slugline with accompanying subjects in all CAPS to denote that we see certain visuals through a particular character’s eyes.

POV OF SOMEONE IN THE WOODS

They watch the couple chasing each other as they head to the beach.

No, this is not a forbidden camera direction, and screenwriters can utilize camera directions like this when the story calls for it.

POV is used for many story-related reasons, including:

- To create mystery and suspense by having visuals being seen from the POV of an unknown person.

- To create an emotional reaction by showing what a particular character is focusing on.

- To showcase the fact that a particular character is seeing a particular element of the story.

- To showcase a particular person, item, or location a character is looking at, informing the reader/audience that they have a particular piece of information others may not.

There’s a caveat, though. If you’re going to use POV, make it pivotal to the story, and don’t use it as a camera direction.

Check out this example from Halloween:

‘Halloween’ (1979)

INSERT

Insert denotes telling the reader that a specific shot of a specific object (and sometimes other elements like a location, stock footage, detail, etc.) is to be seen between the master scene already described.

They are meant to emphasize a different aspect or element of the master scene as portrayed by alternative framing.

An exhausted Lloyd drives down the highway as his eyes open and close.

INSERT – ROAD SIGN

Aspen, 10 Miles

Another example creates an element of suspense.

George walks out of the bathroom, sweating nervously with his hands in his pockets.

INSERT – GEORGE’S HAND HOLDING A REVOLVER

He walks towards the bank teller.

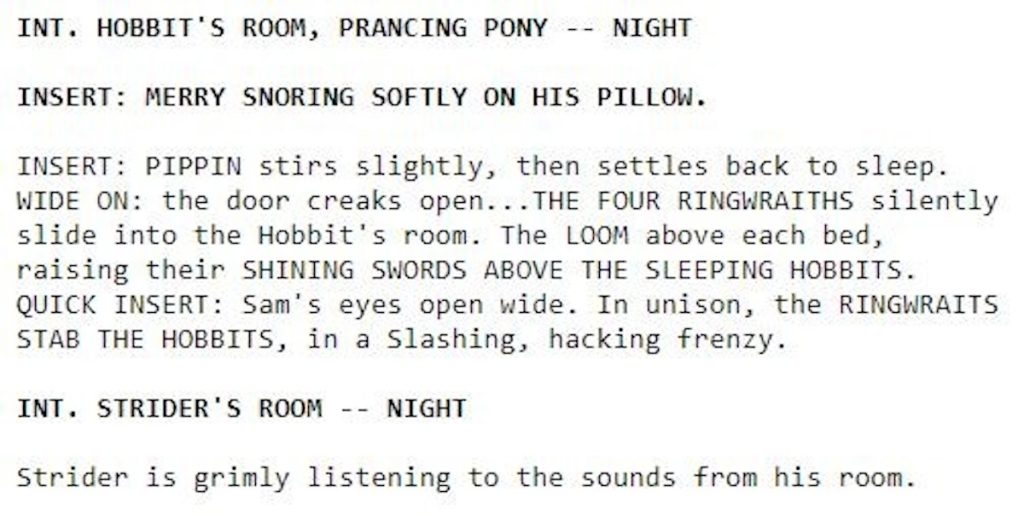

Check out this example from The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring:

‘The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring’ (2001)

—

Yes, this is a camera direction. However, it’s explicitly used for story elements to inform or create added suspense.

And, yes, there’s a caveat as always. Less is more. Only use elements like this few and far between. Otherwise, they get to be annoying for the reader.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed, and many Lifetime thrillers. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies