Exposing the Dark Secrets: Shocking Confessions from Publishing Scam Victims in Episode 14

Ever wonder how some writers effortlessly turn their passion into a thriving career while others…

The Shocking Truth Behind Sharing My Book Title With a Stranger Revealed!

Ever found yourself clutching the “perfect” book title — that gleaming nugget of genius you…

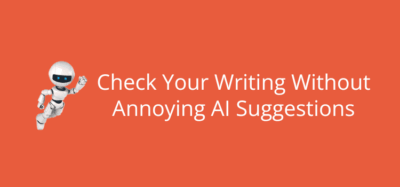

Unlocking the Secret Language of Punctuation: Why Dashes and Hyphens Could Change How You Write Forever

You ever stop mid-sentence—fingers poised over the keyboard—wondering, "Is that little horizontal line a dash,…

Unveiling the Haunting Journey of Carcosa: A Poem That Blurs the Lines Between Reality and Memory

Peering into a shattered world where echoes once thundered but now lie silent, this poem…

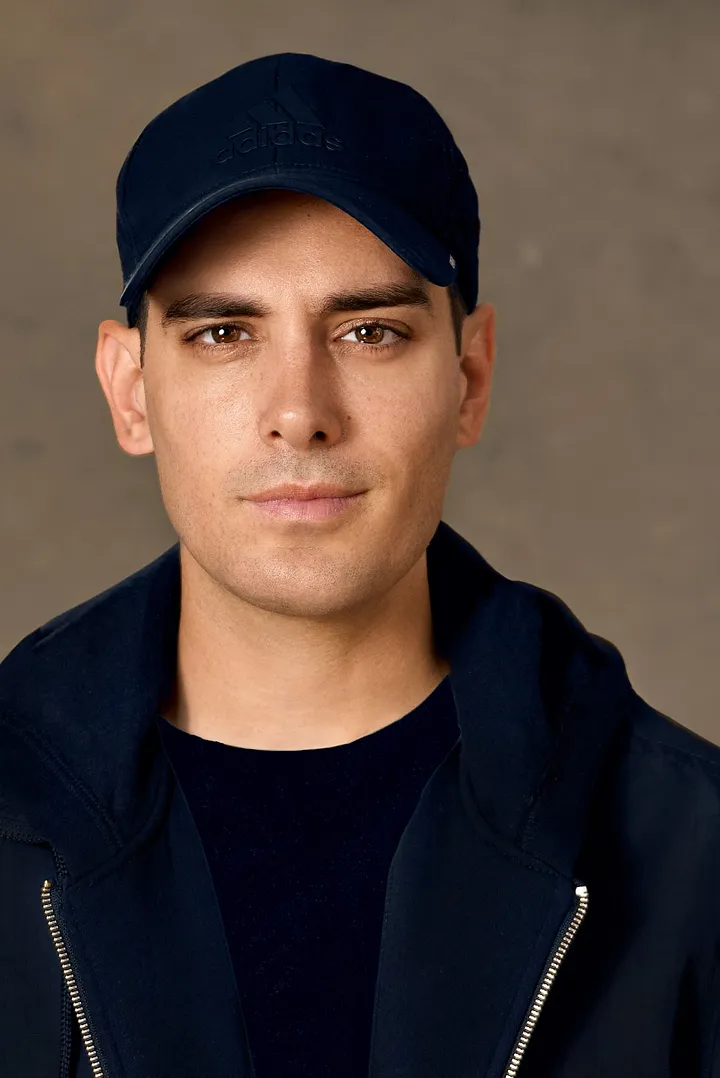

Unlock the Hidden Secrets Behind Justin Colón’s Revolutionary Writing Method—Are You Ready to Transform Your Words?

Ever wonder how a kitchen table, a steady stream of coffee, and a dash of…

Unlock the Secret to a Captivating Writer’s Voice That Readers Can’t Ignore

Ever wondered what people really mean when they talk about a writer’s "voice"? It’s the…

Discover the Hidden Depths in G. S. Katz’s Brief but Powerful Poem “Short and Sweet”

Isn’t it fascinating how some of the richest treasures in life aren’t minted coins or…

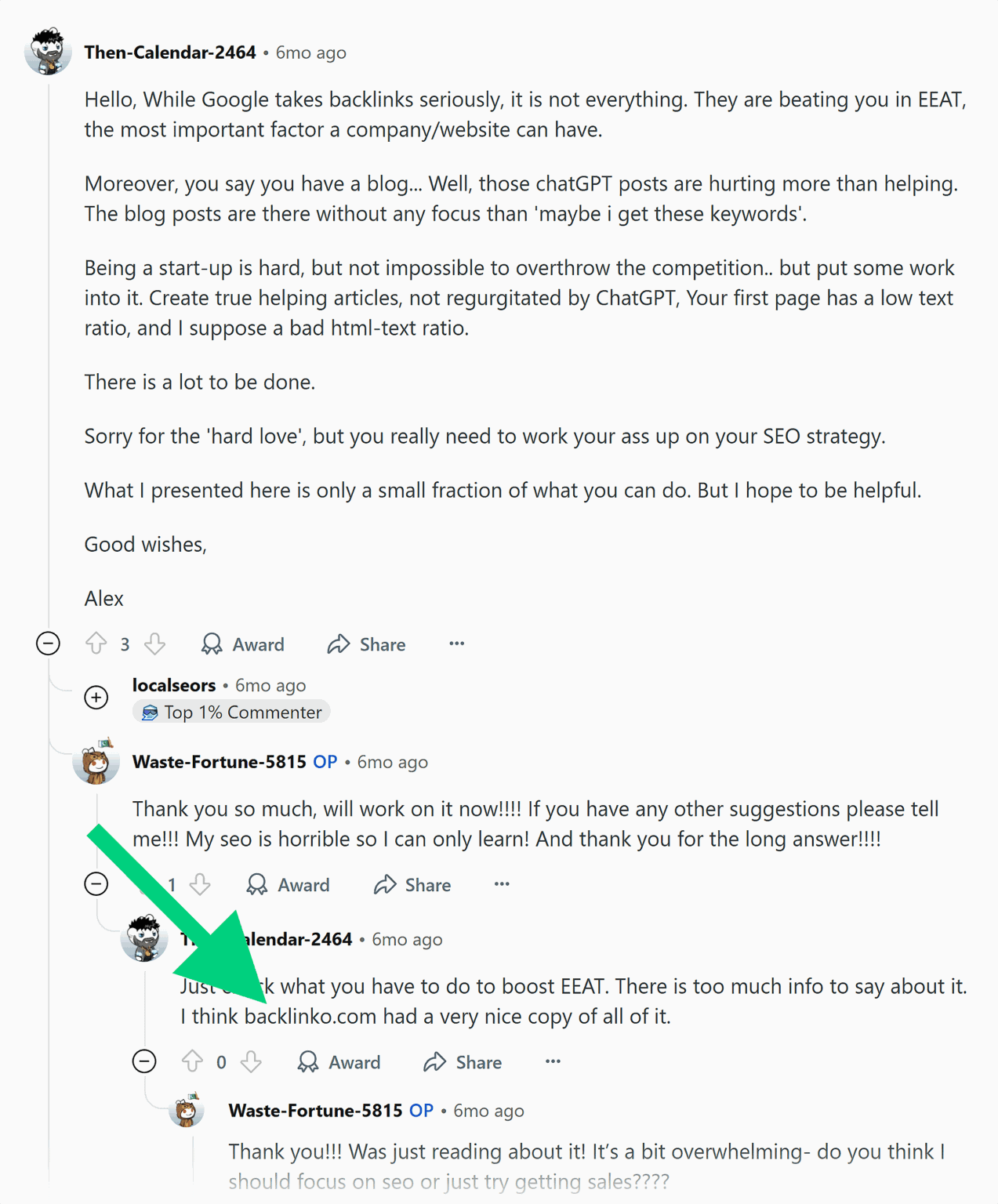

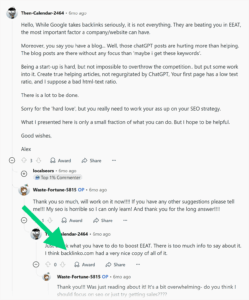

Unlock the Secret Strategy Behind Generative Engine Optimization That’s Revolutionizing AI Search Forever

Ever wondered why your brand might suddenly become the wallflower at the AI-generated dance party…

Unveiling Hidden Depths: G. S. Katz’s Poetic Tribute to Raymond Carver That Will Change How You See His Work

Have you ever wondered how a master wordsmith like Raymond Carver would twist today’s turmoil…

Unlocking the Mystery: How Nonsensical Dreams Secretly Ignite Your Best Writing Ideas

Ever woken up from a dream that felt less like your own and more like…