American auteur Francis Ford Coppola joined Letterboxd weeks before the release of his film Megalopolis to grace cinephiles and filmmakers everywhere with a list of movies titled “Movies That I Highly Recommend.” The list features 20 films—with a handful of them reaching back to the end of the Silent Film era—that poke at the best and most experimental movies ever made.

“Here is a list of films that I enjoy and recommend to any fan of cinema or aspiring filmmaker,” Coppola wrote on the movie-based social media platform. “This list is NOT complete as there are so many—the list is exhausting and goes on and on. I am thankful to Letterboxd for providing such a platform for me to share these meaningful films, show appreciation to the pictures that inspired me!”

Whether you are writing your first screenplay or drafting your 50th, there are a lot of great films on this list. We pulled lessons from each movie Coppola recommended for you to implement into your writing workflow.

French Cancan (1955)

A lot is going on in this rich French-Italian musical written by Jean Renoir. The film follows Henri (Jean Gabin) as he tries to revitalize his café through the can-can. While the film is a gorgeous watch, the attention to detail in each scene and the blocking adds a level of depth to an already textured story. Although a screenwriter shouldn’t add too many details in their action lines, using sharp and poignant language can help flesh out your world for the reader.

Read More: How the Camera Rig in ‘Bad Boys 4’ Can Inspire Action Screenwriters

The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

In this loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Akira Kurosawa breathes new life into a well-known story by infusing it with brutality and sardonic humor. From a wedding cake designed to resemble a corporate headquarters to the moral clashes in the corrupt boardrooms of postwar Japan, The Bad Sleep Well seamlessly blends Shakespearean themes with the contemporary culture of the time.

The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933)

While The Bitter Tea of General Yen is the lesser-known work of Frank Capra, the film reflects many of Coppola’s own tendencies when it comes to storytelling. It is important to note that the film depicts white actors portraying Asian characters, but there is value in the film for its ability to risk offense in its story. The film touches on politics, religion, culture, and sexual desire—all subjects of extreme taboo in American culture to this day.

Shanghai Express (1932)

Loosely based on the Lincheng Incident, Shanghai Express is one of the most technically stunning films of all time. However, screenwriters should focus on how the relationships play out on screen. The subtle details—whether in action or dialogue—reveal much about the characters’ relationships and the expectations they hold for each other and themselves.

The Awful Truth (1937)

Based on the stage play of the same name, The Awful Truth is a screwball comedy driven by the pride and stubbornness of its main characters, Jerry (Cary Grant) and Lucy (Irene Dunne), whose actions create more problems than solutions. While Quentin Tarantino is known for his lyrical dialogue, writer Viña Delmar’s script in The Awful Truth flows with a similar elegance, drawing the audience into the rhythm of the characters’ verbal sparring. The dialogue not only enhances the comedy but also sets the stage for the physical humor, creating a visual contrast that amplifies the film’s wit.

Read More: 5 Insiders to Know if You Write Comedy

The Ladies Man (1961)

As the only man working in a women-only hotel, Jerry Lewis’s The Ladies Man might sound like the setup for a raunchy sex comedy—one that seems to thrive every 20 years. However, this character-driven comedy was unlike anything seen before, thanks to its willingness to deviate from traditional storytelling structures. Instead of following a conventional plot, the film takes an episodic approach, with Herbert H. Heebert (Lewis) moving from one zany comedic situation to another as he interacts with the various women.

The Burmese Harp (1956)

This war drama delves deeply into the moral chaos of conflict and the effects of blind patriotism. The Burmese Harp presents a simple story with a universal humanist appeal. Its narrative is clear and executed with near perfection, teaching screenwriters that the best stories focus on the contemplation of morality.

Tokyo Story (1953)

Often regarded as Yasujiro Ozu’s masterpiece, Tokyo Story stands out for its ability to look at the mundane and universal challenges that a family faces in their day-to-day life as members of the middle class. The characters’ behaviors and motives are instantly recognizable to anyone, no matter how selfish their actions may be. Because the story is so universal, the story is allowed to hold back on being too explicit with its actions or dialogue, allowing more room for audiences to explore the complexity of a home drama.

The Last Laugh (1924)

Many films from this cinema era are often the most revolutionary. The Last Laugh is no different as it gives the camera the freedom to explore a set rather than sitting stagnant in a scene. This German tragedy can teach screenwriters how to write and use action to convey tone without thinking of the constraints of the format.

The Blue Angel (1930)

Josef von Sternberg’s seminal film stands out for its pioneering use of sound in film, but screenwriters should focus on the rich character development that doesn’t rely on stereotypes that were considered old and worn by the 1930s. Characters are allowed to show their complexity without negative reproduction of their trope elements, allowing them to become three-dimensional characters that explore their own arc throughout the film’s plot.

Splendor in the Grass (1961)

Hollywood loves a happy ending, but not every story can make an impact if everything works out in the end. Splendor in the Grass is one of those films with a bittersweet ending that leaves a lasting emotional impact. While the film’s ending finds closure for Deanie (Natalie Wood), it is not a traditional “happy ending.” Impactful endings don’t always need to be neatly resolved. Instead, they would pack a punch that reflects the complexities of the themes the story deals with.

Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

Utilizing Adam Sandler’s comic persona in a similar way that Jim Carry’s physical comedy lends itself to drama, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love is a whirlwind of a romance that leans toward the unconventional. But it works thanks to the sympathetic energy the PTA writes the anxious and lonely love-sick character with. Even when the character flies on a whim to Hawaii to chase a girl, it feels weirdly romantic. Writing characters at odds with the world can be challenging if you can’t find the empathic thread that launches them into their character arc.

Empire of the Sun (1987)

Despite being one of Steven Spielberg’s more underrated movies, Empire of the Sun is a brilliant war epic told through the perspective of a child. Screenwriter Tom Stoppard blends true events with fiction to create a story that feels authentic and yet cinematically compelling. It is a tricky balance to find—one that will often receive comments from historians—but it is crucial when crafting an engaging story that doesn’t feel like a history lesson.

Read More: 5 Trademarks of Steven Spielberg Movies

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

Often regarded as the silent film of the Silent Film era, Sunrise is carefully crafted to set the standard of motion pictures. Following a three-act structure, the film’s simple plot is effective using the straightforward narrative to build themes, characters, and tone. As the acts come to an end, the pacing builds and releases tension effectively as the story pushes forward.

The Joyless Street (1925)

While it may seem distant from contemporary screenwriting, G.W. Pabst’s silent film can still teach screenwriters the power of subtly. The film weaves social issues about living conditions in post-World War I Vienna into the narrative in a way that feels organic. Characters are not talking outwardly about their problems, but are showing the audience their day-to-day struggles while maintaining a compelling story arc.

A Place in the Sun (1951)

While the film’s commentary is not revolutionary in the modern era, many consider this slow-paced melodrama to be a staple in American cinema. The film touched on taboo subjects through subtext, smartly implying a key plot point through sharply written dialogue between Angela (Elizabeth Taylor) and her doctor. If writers want to touch on subjects that are taboo to the public, using smart dialogue can add to the story’s strength without saying anything directly.

The King of Comedy (1982)

Martin Scorsese has long been known for his complex anti-heroes, and Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) is no different. Playing into America’s obsession with celebrity and media, Scorsese balances the humor and the tragedy of a comedian desperate for a moment in the spotlight. Rupert’s conflict makes the anti-hero sympathetic enough to root for him, even if he makes our skin crawl. Writers can learn how to craft a compelling anti-hero that will do anything to get what they want, believing what they are doing is the right thing (well, most of the time).

After Hours (1985)

What could go wrong in one night? Scorsese returns to the brutal streets of After Hours for his comedy of errors. Each scene bleeds into the next, building on top of the insanity Paul (Griffin Dunne) endures in a single night. Writing a movie that takes place in a limited time and is motivated by external forces that push the character further into the growing madness isn’t an easy task, but it’s a great challenge that screenwriters should try to take on.

Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

This quintessential Polish film walks the tightrope with its audiences by touching on a subject that could offend either the audience or the regime. Andrzej Wajda’s awareness of this tightrope can be felt in the story, intriguing audiences to look closer at the text. Sometimes, ambiguity is a good thing. Writers can use it to omit their opinions on a touchy subject, allowing the art to spark a conversation in the audience.

Invitation to the Dance (1956)

What can writers learn from a movie that basically has no dialogue? They can learn a lot about action. Similar to the silent film era, Gene Kelly’s dance anthology film tells stories through action. The best films can convey tone and theme through action alone, without relying on dialogue. Try writing a script that has no dialogue as an exercise to see how well you are telling a story through action instead of words.

—

Whether the films are silent, foreign, or some of your personal favorites that have already inspired your craft, Coppola’s endorsement indicates that he found something special and important in each story.

As writers, a crucial part of our craft is to watch, learn, and experiment to enhance our skills. Don’t be afraid to try and fail with this advice. After all, improvement comes only from the willingness to attempt.

Read More: Thinking of Quitting Your Screenwriting Dream? Here’s Some Inspiration…

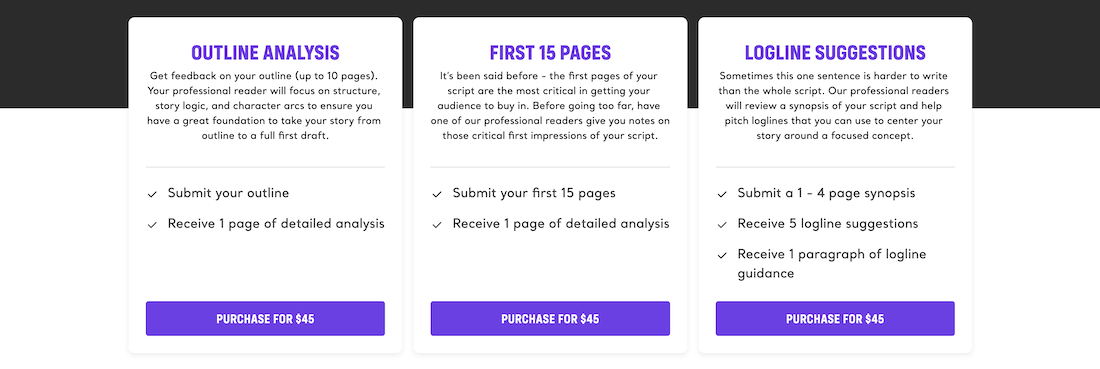

Check out our Preparation Notes so you start your story off on the right track!

The post What Francis Ford Coppola Letterboxd Picks Teach You About Screenwriting appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Alyssa Miller