What I Discovered Behind the Scenes of a $3,000 Writers Retreat with Bestselling Authors Will Shock You

Powerful storytelling focuses on decisions, not the events or outcomes

In a writing retreat I attended as a scholarship awardee (the standard package is about $3,000, but I attended for free), we analyzed why certain personal stories grab readers while others fail to engross and capture.

One pattern kept emerging: the most engaging pieces didn’t just focus on what happened or the emotions around it. Instead, they showed, through the story, how the writer made decisions that had a big impact on their life and the story they’re telling now.

This doesn’t mean circumstances or results don’t matter. External events provide the context and stakes that make decisions meaningful and shape the story arc. But when writers focus only on what happened to them and how they felt, the stories tend to feel passive and distant.

Here’s how to find the decision-making moments that help your personal stories connect more with your readers.

Look for the “hidden” choices

“Hidden choices” are the decisions we make that don’t feel like decisions at the time. They’re often so automatic or seem so obvious that we don’t recognize them as active choices when we’re writing our stories.

These typically fall into three categories:

- Choices we made without thinking. When I was unemployed and sending out generic job applications, I didn’t think “I’m choosing to use the same approach that isn’t working.” It felt like I was just doing what you’re supposed to do when job hunting. But staying with familiar strategies instead of trying something different was absolutely a choice.

- Decisions not to act. In memoirs about difficult relationships, writers often focus on what the other person did wrong while overlooking their own choice not to set boundaries, not to have difficult conversations, or not to leave earlier. Inaction is still action.

- Assumptions that guided behavior. These are the beliefs we never questioned that shaped how we responded to situations. I have a friend who kept getting overwhelmed by constant interruptions at work, until she realized she’d always assumed that when someone knocked on her office door, she had to stop what she was doing and help them immediately. She’d never considered that saying “Can you come back in 30 minutes?” was an option.

In both memoirs and articles that use a personal lens, the most compelling sections usually reveal these hidden choices.

When you’re drafting a personal story, try to go through each major event and ask yourself:

- “What did I choose to do here that I haven’t mentioned?”

- “What didn’t I do that I could have?”

- “What assumptions was I operating under?”

Often these overlooked decisions contain the most interesting parts of any story.

Show the moment when options became clear

One summer afternoon, I came across a group of university girls in their preppy summer dresses, and I realized that my prospects looked very dark.

The “summer girls” were on their way out of our residential building, probably off to some hip weekend party with friends. I, on the other hand, had $23 in my pocket and exactly 15 days left to materialize enough funds to pay the rent. Otherwise, my landlord would kick me out. The countless job applications and freelance project proposals I had sent all over were either rejected or ignored.

In contrast to those girls in their designer summer dresses and carefree days, I was broke, unemployed, and alone… Later, I was mooching off a coffee shop’s free Wi-Fi, searching for articles that can give me a better perspective, when I started typing: “How to fix a failed career.” Immediately, Google provided suggestions: “How to fix a failed career at 30… 40… 50.” It was both scary and reassuring.

It was scary, because it felt that my failure was all too real; and reassuring to know that so many people out there were experiencing the same thing (or worse)…

The above was part of the opening section of an article I sent to a publication about seven years ago.

At the time, I had just been let go from my tech startup job, and I had been fruitlessly hunting for jobs and clients for months. I initially wrote the piece to vent. When I first tried writing about the experience, I mostly focused on the job market, the rejections, the financial stress. The story felt flat because I was just describing circumstances.

The shift happened when I started examining the decision point.

In reality, I didn’t get a major epiphany when I saw the “summer girls.” Instead, I got home, began eating a bowl of muesli, and the thought struck me: Is there any other way for me to get out of this hole?

That thinking process eventually led to the final, better edits I made to the piece, which turned it into something readers could appreciate more.

And because I saw the “summer girls” just before the thought struck, and since their appearance was such a natural foil to my situation, I began writing the article using that story, that decision point, as the intro.

Experiences that feel overwhelming often contain more decisions than we realize

The decision to re-angle my thinking wasn’t necessarily all that dramatic when you think about it. It wasn’t something as visual as someone having a complete career meltdown and deciding to become a travel blogger or start their own company, like you usually see in movies about reinventing yourself. It was a quieter, more subdued, maybe even calculated decision. But this decision revealed to my readers how I respond to crisis.

After the piece got published, I started getting emails. Then I booked a couple of meetings.

That article led me to two long-term clients who’d eventually pay me more than I earned from my job at the tech startup (which relatively paid really well already). Maybe it’s also good luck. But thanks to that article and the folks who reached out, I got to pay my rent and restore my confidence at the time.

So, happy ending! And like any pro writer, here I am sharing that story with you now so you can hopefully gain some value from my experience.

How to find your decision points

These moments can be tricky in that they rarely announce themselves. Most of my interesting decision points only became clear when I was revising, not while I was living through them.

Here’s what I’ve learned works: instead of trying to identify decisions while you’re drafting, write the story first focusing on what happened. Get the events down. Get the interiority down (thoughts, feelings, reactions, inner struggles). Then go back and look for the gaps.

The gaps are usually places where something changed but you haven’t explained how or why.

- Maybe your attitude shifted.

- Maybe you started behaving differently.

- Maybe you stopped doing something you’d been doing consistently.

In my unemployment story, there was a gap between “sending out endless applications” and “deciding to write an article.” When I examined that gap, I found the real decision point: sitting at home with a bowl of muesli, asking myself if there was another way out.

The summer girls scene happened, but, as I said, it wasn’t actually when I made the choice. It was just good visual contrast for the story, so I used it as the opening. That’s the kind of narrative shaping that happens in revision.

Most writers skip this revision step. They write what happened and assume that’s the story. But the story usually lives in those gaps between events.

Another place to look: moments when you surprised yourself. Times when you did something that felt unlike you, or when other people reacted in ways you didn’t expect. Those reactions often point to choices you made without realizing it.

Working with other writers helps spot these blind spots in your own experiences.

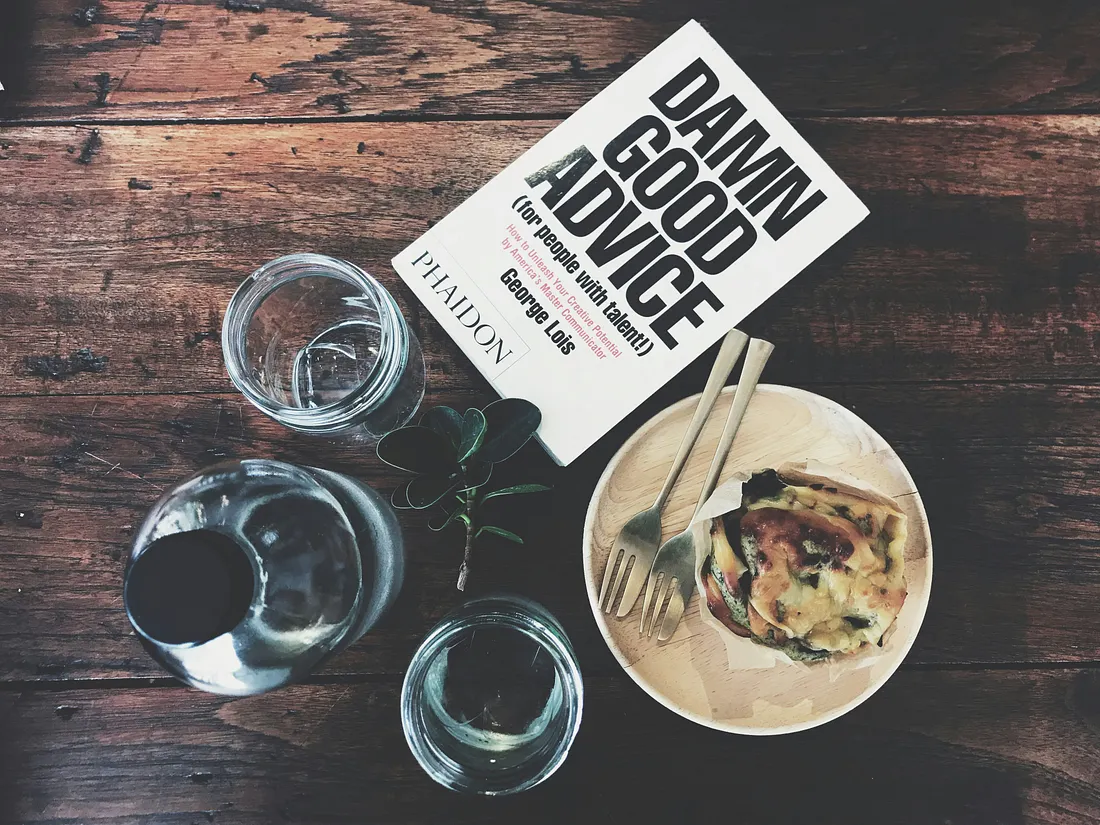

A few months ago, I attended the Iceland Writers Retreat, in Reykjavik, which creates exactly this kind of collaborative environment for examining our stories more carefully.

Gathering with experienced and successful writers, along with writers in varying stages of a writing career, is both eye-opening and inspiring. And I highly recommend it.

Quiet but “inevitable” decisions

This doesn’t mean you need to turn every story into a dramatic moment of choice. The most interesting decisions are often the quiet ones, the ones that felt inevitable at the time but reveal something about how you navigate problems.

The unemployment article worked not because I made some brilliant strategic decision, but because I showed readers a moment when I stopped doing what wasn’t working and tried something different. That’s something most people can relate to, even if their circumstances are completely different.

When you’re revising your personal stories, spend time in those gaps between events. Ask what changed and how. Look for the moments when you shifted direction, even slightly.

Those shifts often contain the most engaging parts of any story, and they’re usually hiding in plain sight.

P.S. The Iceland Writers Retreat is raising funds for 2026 scholarships that cover airfare, lodging, and tuition for writers who can’t afford them. They must hit their funding goal by September 15, 2025, or no scholarships are given. As a 2025 scholarship recipient, I can say it was life-changing. If you want to help uplift marginalized writers, please donate or share: icelandwritersretreat.com/scholarships