Every screenwriter has completed a polish draft on their own—hopefully many. In the final stage, you conduct last-second checks for grammar, spelling, and formatting errors; read through your script to quicken the pacing; whittle down the dialogue to its core in each line; ensure that your story and structure are consistent; and add creative oreshadowing, plants, and payoffs throughout the script.

These are the things every screenwriter should be doing before they send in any draft to any competition, fellowship, or industry insider. You do all you can to make your script the best it can possibly be in your eyes and capabilities. With that known, we’re not discussing that type of polish draft (check out our final draft checklist for that).

Instead, we’re taking it to the next level to discuss what entails writing a professionally polished draft.

What Is a Professional Polish Draft?

A professional polish draft is one that a screenwriter is contractually obligated to write while under contract with a production company, streamer, network, or studio. Polish rewrites are even detailed in the Writer’s Guild of America Schedule of Minimums, which mandates guild minimums for guild members under guild signatory contracts. We’ll be discussing both guild and non-guild professional polish rewrites in this section.

Typically, the average industry contract—whether guild or non-guild—breaks down like this:

- Either you sold a script and are contractually allowed the first go-ahead on the initial rewrite or you’ve been assigned to write a screenplay based on your employer’s intellectual property or idea.

- If you’ve sold the script to them, disregard this contractual step. If you’re under assignment, the first thing you will need to do is write an outline. This is usually the first pay level of your assignment contract.

- Once you request the first rewrite, you’ll generally have two weeks to a month to complete it, with two weeks being the usual timeframe.

- Once you hand that rewrite in, you’ll likely be given more notes for another, unless you are replaced. Rinse and repeat.

- But then, if you haven’t been replaced, once the script is close to going into production, you’re going to be asked to do a polish rewrite likely.

What Does a Polish Draft Entail?

A polish rewrite involves making minor requested changes to various elements of the script, all aimed at preparing the script for production.

At this stage, polish does not include substantial changes to the plot, character arcs, structure, or major scenes or sequences. That’s what a rewrite entails.

Instead, you’re tasked with tweaking the script to the point where it can go out to the crew and the cast, and be cemented as the official shooting draft of the script.

What Changes Do You Make in a Polish Draft?

The answer to this question will depend on the case-by-case scenario of each screenwriting contract and production. However, here are the general guidelines on what to expect in notes for a polished draft.

Filling Plot Holes

Plot holes are going to happen. It’s not usually about outright bad screenwriting, especially when you’re working under contract with multiple notes coming your way throughout the whole development, writing, and rewriting process.

You’ll always see in completed features that despite the accolades and box office success of successful films, there are almost always plot holes—big or small—present within the final cut of the film.

The polish draft ensures that plot holes are minimized and kept as small as possible in the overall story.

The notes you receive will identify plot hole concerns that you need to address before production begins.

You’ll need to:

- Delete scenes

- Add scenes

- Cut down scenes

- Extend scenes

All for the betterment of the eventual film.

Touching Up Dialogue

Dialogue is at its best when it is at its lowest amount of words.

Polish drafts will task you with saying as much as possible with the least amount of dialogue. Directors, actors, line producers, and other production people usually know when a scene is too wordy or is going to be too long because of the dialogue.

An overly long scene means more time needed on set, more lines for actors to memorize, and more minutes added to the eventual run-time.

You’ll need to:

- Delete dialogue

- Correct dialogue

- Replace dialogue

- Rewrite dialogue

- Add dialogue for expositional purposes

Typically, clients make these requests by providing page-by-page notes, specifying the page numbers where changes are needed, and offering simple instructions on how to implement them.

Read More: The Single Secret of Writing Great Dialogue

Shortening Scenes

Once again, the film is about to go into production. The production is going to find every way it can to cut down costs and streamline shooting days. Sometimes this means shortening scenes.

This process also influences the film’s pacing. While post-production will officially decide the final timing, why shoot overly long scenes when you can schedule shorter ones to speed up production?

Combining Scenes, Dialogue, and Locations

This is where the production needs come into play. Remember, the movie only starts with the screenplay. Beyond you, there are dozens upon dozens (hundreds for bigger productions) at work prepping for an expensive shoot.

Corners will need to be cut financially. The production will need to take advantage of every single location and shooting day they have.

Because of this, polish rewrites will usually entail you having to combine scenes (which, in turn, involve combining dialogue from one scene to another). And, sometimes, this may mean that you need to utilize the same locations for certain scenes so the eventual production can take advantage of locations and utilize them to their full extent.

Specific Casting Needs

Casting changes happen often. The original script may have a certain type of character in its original draft, only to have the hiring of a certain actor closer to production change the character’s dynamics and necessities when it comes to background, dialogue, dialect, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc.

Little (and sometimes major) tweaks may be necessary right before production.

Budgetary Cuts

The powers that be may need you to cut action sequences, on-location scenes, and any number of other expensive elements in the current draft all because they are trying to tighten their budget and schedule before production begins.

MPAA Ratings Cuts

If your script is full of profanity, nudity, and violence, and the powers that be decide to pursue a PG-13 or PG rating, they will ask you to cut down on those elements to adhere to MPAA Guidelines.

—

Polish drafts are less time-consuming for screenwriters compared to the usual rewriting process. These examples may seem daunting, but they usually come in a simple and easy-to-apply way.

Read More: 7 Studio Jobs That Give Screenwriters an Edge

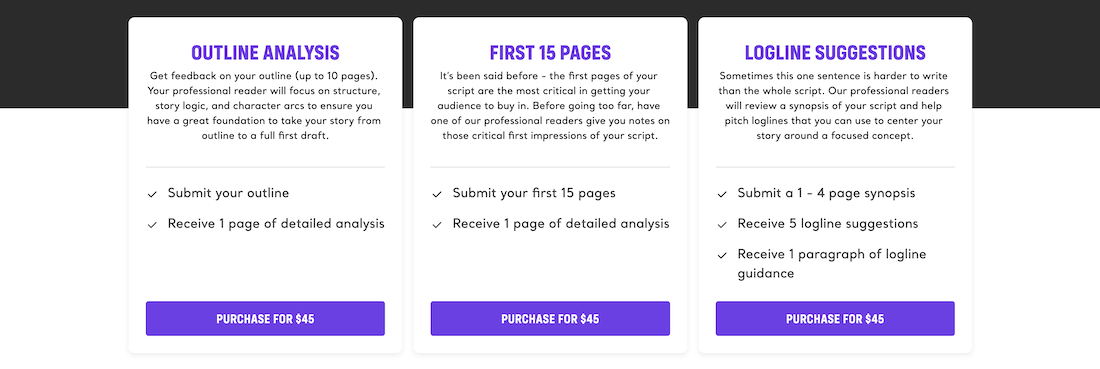

Check out our Preparation Notes so you start your story off on the right track!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed, and many Lifetime thrillers. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies and Instagram @KenMovies76

The post What Is a Professional Polish Draft in Screenwriting? appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Ken Miyamoto