As animation began to grow in appreciation in American culture, audiences already had a deep appreciation for Studio Ghibli. There was an element to Hayao Miyazaki movies and his creative team that brought back a childlike sense of wonder and beauty against a backdrop of reality that could feel cruel and unjust.

Beyond the visuals of Studio Ghibli’s films, which are astonishing on their own accord, Miyazaki’s storytelling is what grounds these films as masterpieces. Kiki’s Delivery Service, the double feature of Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro, and Miyazaki’s latest and last film The Boy and the Heron are stories that are radically at odds with Hollywood storytelling, yet have a level of gravitas that is often overlooked as something wholly unique that can’t be taught. It just is.

While we can’t teach you to create stories like Miyazaki — which is why Studio Ghibli stopped making films for almost a decade–there are trademarks of Miyazaki’s storytelling that we can learn from and mold into our own stories. Let’s get into it.

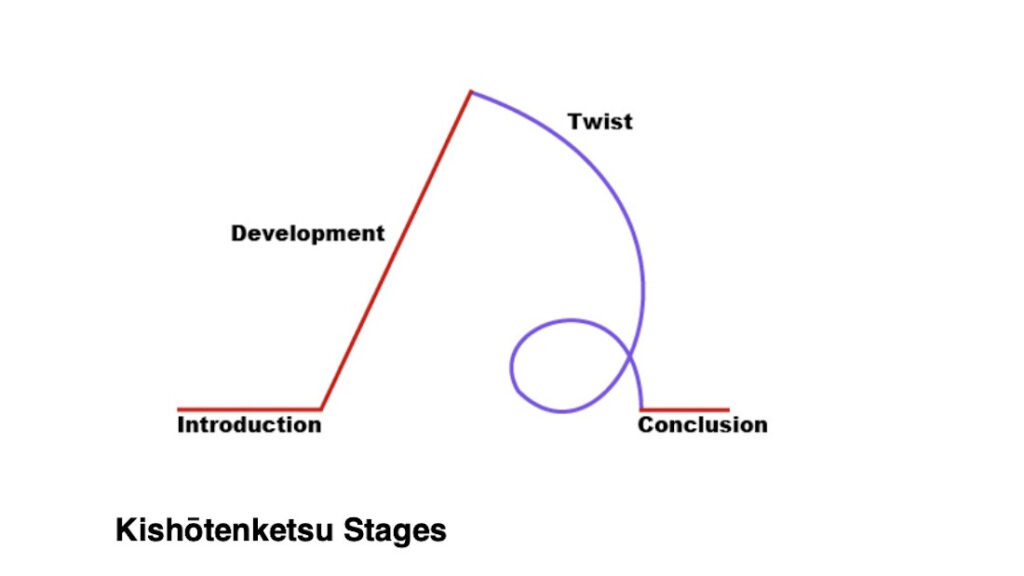

1.) Using the Kishōtenketsu Story Structure

Rather than using the American standard three-act structure to tell his stories, Miyazaki’s stories follow a plot structure known as kishōtenketsu. Used since ancient times in Japan, kishōtenketsu is the method of storytelling composed of four parts: ki (introduction), shō (development), ten (turn or twist), and ketsu (conclusion).

While most stories have a rigged structure that is easy to follow and break down, kishōtenketsu has a wandering quality that can feel unusual to people who are not familiar with East Asian storytelling. The structure lends itself to a long, quiet beginning that is quickly twisted to shake up the story. In the end, the twist is settled, revealing the connecting theme between everything. Miyazaki always uses the kishōtenketsu structure in his storytelling, dividing his story into four parts. In the third part, there is always a big hurdle the hero must overcome to get to the end of the film. While the conflict might impact the story, it is not the focus. Instead, the story features a conflict, but the purpose of the story is the change in the protagonist.

My Neighbor Totoro is the clearest example. It lacks a conflict, which has led many American critics to believe that nothing happens in the film. But the kishōtenketsu structure is at work, revealing that Satsuki and Mei are attempting to adjust to life without their mother. The sudden twist of Mei running away is shocking, but order is quickly restored. It is an easy film with a structure that isn’t overwhelming. There is more than one type of structure out there in the world of storytelling beyond the three-act structure. It is up to you to decide what type of structure fits your style of storytelling.

Read More: The Simple Guide to Writing Animated Screenplays

2.) Unfinished Scripts

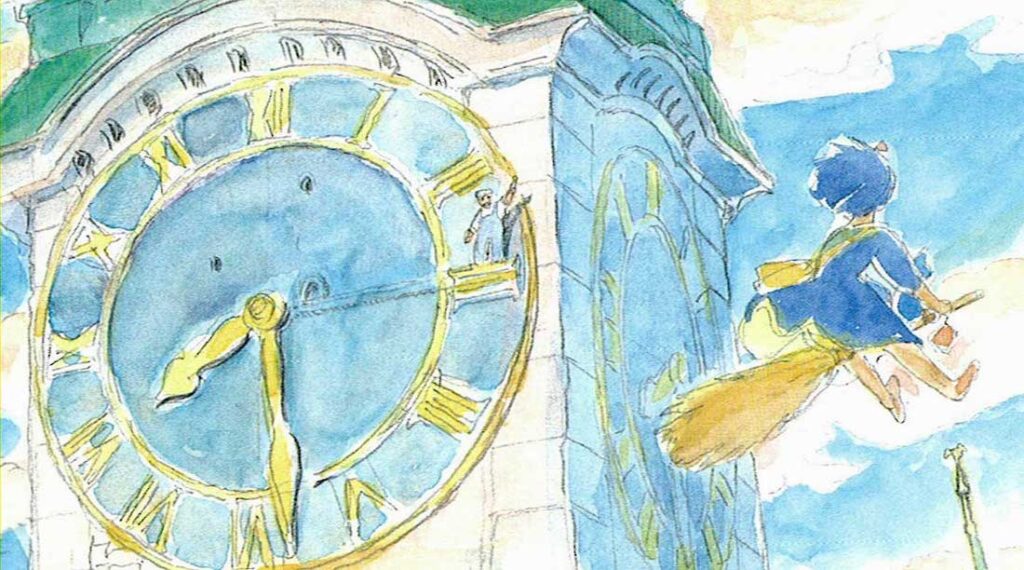

While the structure of Miyazaki’s stories is set, he typically doesn’t finish the story once his team is ready to start working on a film. A key part of Miyazaki’s filmmaking process is the creation of storyboards, a series of images that help map out a movie’s sequence of events. While storyboarding is an essential part of the animation process, Miyazaki tends to forego screenplays of spontaneity.

“I don’t have the story finished and ready when we start work on a film,” he said in a 2002 interview. “I usually don’t have the time. So the story develops when I start drawing storyboards. The production starts very soon thereafter, while the storyboards are still developing. We never know where the story will go but we just keeping working on the film as it develops. It’s a dangerous way to make an animation film and I would like it to be different, but unfortunately, that’s the way I work and everyone else is kind of forced to subject themselves to it.”

At the core of his process, Miyazaki’s goal is to capture the beauty of the world he is creating. He can’t fully or clearly see them, nor does he know how his stories will end. Miyazaki leads the group of animators to find the film based on the few ideas he brings to them.

Takahata, Miyazaki’s late mentor, explained the process in the 2000s:

Hayao Miyazaki stopped writing screenplays a long time ago. He doesn’t even bother to first finalize the storyboards. … After diving into the process, he then begins to create storyboards while doing all his other work, from key animation on down. Using his powers of continuous concentration, the production starts to take on the elements of an endlessly improvised performance.

Read More: Hayao Miyazaki Says ‘Ma’ is an Essential Storytelling Tool

Storyboard from ‘Kiki’s Delivery Service’

3.) Female Protagonist

In a majority of Miyazaki’s films, the story is driven by strong female leads, who are brave girls or women who don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe is right. Inspired heavily by his own mother, Miyazaki’s female characters are complex and conflicted, like Princess Kushana in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke, and the witches Yubaba and Zeniba in Spirited Away.

Miyazaki stated, “In my family, it was a very male universe. I only have brothers, the only woman was my mother.” Miyazaki is one of four brothers. Perhaps this is why mother figures in his work have such a grounding nature, while the female leads, inspired by his mother, are on a quest for self-fulfillment, helping each other and humanity along the way. They share a universal language of compassion, tolerance, and fairness. These female leads do not want to be anything other than themselves, which is a powerful message in itself.

‘Princess Mononoke’

4.) Flying Scenes

Another childhood influence in Miyazaki’s work is his love for airplanes, particularly old ones. His family owned a company that produced wingtips for Zero fighters, and this is possibly what has led to each of Miyazaki’s stories containing flying scenes of some kind. From Tombo’s flying bicycle in Kiki’s Delivery Service to Haku’s transformation into a flying dragon that Chihiro eventually rides in Spirited Away, flying has become a staple of Miyazaki’s work.

While flying is a key trademark of Miyazaki’s storytelling, the filmmaker tends to stay away from military aircraft. Miyazaki released the destructive power of military aircraft. This feeling of conflict Miyazaki feels is highlighted in The Wind Rises when Jiro Horikoshi dreams of building planes, but realizes the consequences that warplanes can have.

‘The Wind Rises’

5.) Conflicts Solved Through Pacifism

What makes Hayao Miyazaki movies so beloved by a wide range of audiences is that his films do not depict any violence. That’s because Miyazaki, who grew up during World War II, despises unnecessary violence and advocates for pacifism through his stories.

In multiple interviews that Kotaku found through Japanese blogs, Miyazaki spoke out about his disdain for violence in Hollywood films, saying, “If someone is the enemy, it’s okay to kill endless numbers of them. Lord of the Rings is like that. If it’s the enemy, there’s killing without separation between civilians and soldiers. That falls within collateral damage.”

Hayao Miyazaki movies share a common theme that disputes can be resolved without the use of physical force. Castle in the Sky, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Princess Mononoke are examples of this since the main characters strive to bring peace to a world filled with conflict. Of course, physical confrontations are also present, but they are used to point out the uselessness of it.

‘Howl’s Moving Castle’

—

Hayao Miyazaki movies are beautiful and meticulously crafted, taking a single film year to build from the few ideas that Miyazaki brings to his team at Studio Ghibli. While there are several trademarks that signify that a story belongs to this filmmaker, Miyazaki’s scripts are almost non-existent. Everything lives in the storyboards. While it is highly recommended that you finish a script before moving into the production process, there is beauty and a level of acceptance to Miyazaki’s creative process.

Read More: 101 Enchanting Animation Story Prompts

The post 5 Trademarks of a Hayao Miyazaki Movies appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Alyssa Miller