“Unmasking Manipulation: 8 Subtle Phrases That Erode Your Self-Worth Without You Realizing It”

Have you ever found yourself in a conversation that left you feeling small, doubting your…

“Unlocking Strength: Discover the Hidden Depths of Stan Morrison’s Enigmatic Poem ‘Power Piece'”

What happens when you mix a playful curiosity with a dash of danger? The poem…

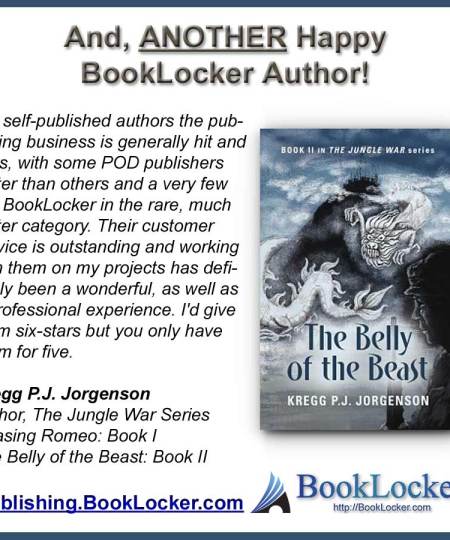

“Unlocking the Secrets: How to Thrive as a Writer Without Compromising Your Integrity!”

Have you ever thought about how super-specializing in a niche can catapult your writing career?…

“Is Your Adult Child Struggling in Silence? 8 Alarming Signs You Must Not Ignore!”

Navigating the journey of parenthood isn’t for the faint of heart, especially when your children…

“Unlocking the Secrets: How Your Support Can Empower Writers Like Never Before!”

In a world where the essential workers—those who educate our children, feed us, and protect…

“Unlock the Secrets to Timeless Respect: 8 Daily Habits That Make You Unforgettable as You Age!”

As we journey through life, the passage of time inevitably leaves its marks. But here's…

“Unveiling the Secrets of Mount Auburn: Jessica Beck’s Poetic Journey Through Nature’s Hidden Stories”

Have you ever found yourself pondering the interplay between life’s fleeting moments and the eternal…

“Unlocking the Secrets: 8 Surprising Traits That Reveal a Man’s True Kindness and Beauty Within”

Recognizing a man with a kind and beautiful heart has always been an intriguing pursuit…

“Unlocking the Mystery: Why the Choice of Pronouns After ‘Than’, ‘As’, and ‘Like’ Could Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Comparisons!”

Isn't it intriguing how a simple word can spark a fierce debate among avid grammarians?…

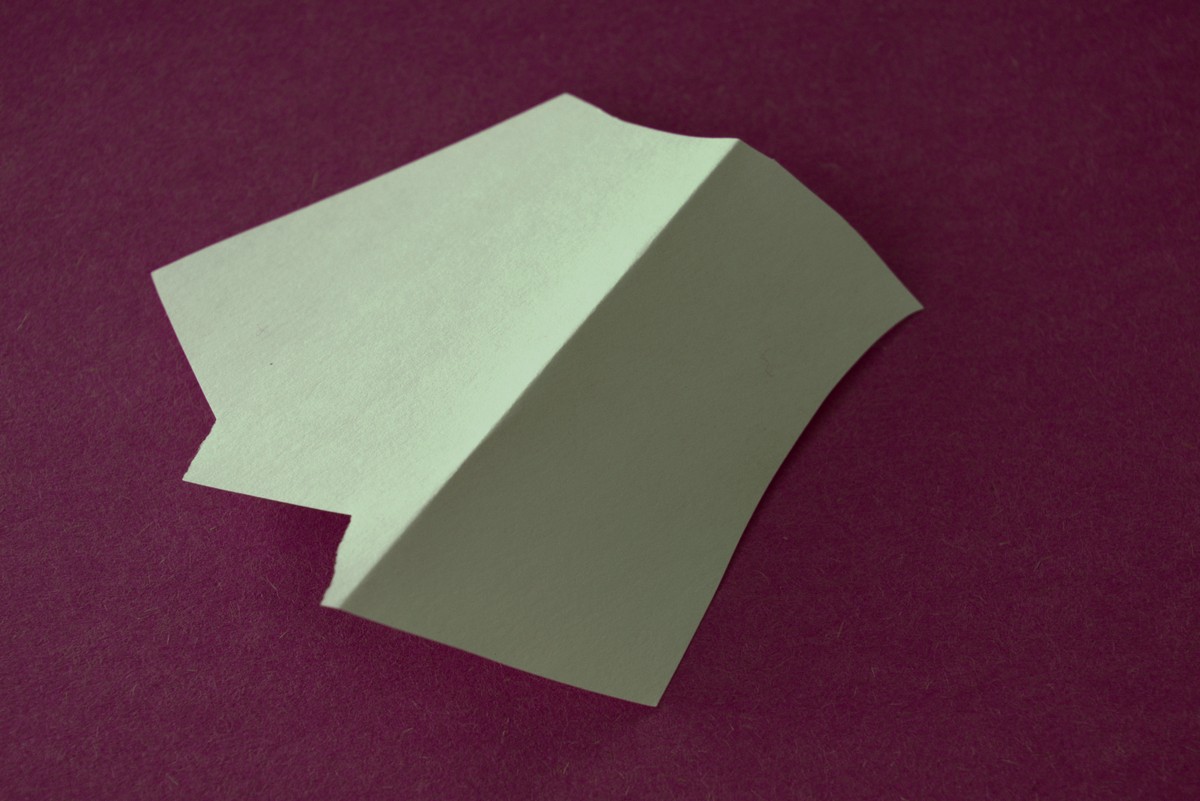

“Unlocking the Silence: Discover the Hidden Depths of Dah’s Enigmatic Poem ‘Blank'”

In a world swirling with chaos and noise, have you ever paused to wonder about…