Screenplays are very different from literary short stories and novels. They are written specifically for the visual mediums of film and television. In movies and TV shows, there’s (generally) no place for inner dialogue, extreme detail in description and numerous tangent chapters. Screenwriters write blueprints for stories that fit within a two-hour (give or take) feature, thirty-minute sitcom episode, or hour-long (give or take) dramatic episode. And it’s best when those scripts are written cinematically to grab the reader and pull them into the story that will someday become a movie.

What are the most essential elements of cinematic screenplays? Here are some general guidelines.

5 Elements of Cinematic Screenplays

1. A Focus on Actions and Reactions

Because film and television are visual mediums, audiences want the story to be told through actions and reactions. A screenplay that focuses more on showing rather than telling is a sign of a cinematic screenplay. Action and reactions allow the cinematic story to flow at a quicker pace.

- Introduce the conflict.

- Show the characters reacting to the conflict.

- Show the consequences of their actions.

- And have them react to those consequences.

2. Smaller Story Windows and Streamlined Timelines

In the film Lincoln, Steven Spielberg could have tried to depict the whole presidency of Abraham Lincoln but wisely decided on choosing a smaller story window within his presidency — in this case, Lincoln’s struggle to emancipate the slaves.

That allowed for a more cinematic experience for the audience than what could equate to a documentary by showcasing his whole story.

Read More: How to Succeed the Steven Spielberg Way

In the book version of Lords of the Rings: The Two Towers, Tolkien spends 200 pages with one set of the Fellowship. Then he goes back in time to cover Frodo and Sam’s journey into Mordor. This would be a questionable narrative structure choice in a film. The cinematic option was to cut back and forth between those storylines. That offered a more streamlined cinematic feel.

Read More: The Hero’s Journey Breakdown: The Lord of the Rings

Presenting the story’s structure in a more streamlined fashion helps keep the audience focused on the chronological structure of the narrative. When you keep the timelines between different storylines simple and chronological, you present a more cinematic experience for the script reader and audience.

3. Swift Scene Description

Scene description holds the key to the success of your cinematic screenplay. You want the reader to decipher the visuals you are describing in your scene description as quickly as possible — as if they were reels of film flashing before their eyes.

Read More: Essential Movies Taught in Film School

Sadly, most novice screenwriters fail to understand the importance of writing cinematically. Instead, they either focus on directing the camera or go into specific detail with long-winded scene descriptions and prose.

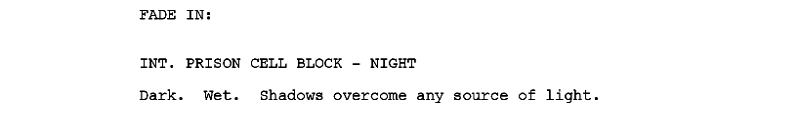

In this first example, we have scene description that is more interested in prose than it is presenting a visual.

This scene description block isn’t the worst we’ve seen. Two sentences in one block and one long sentence in another. A lesser writer would have used another paragraph to go further into detail, trying to capture some particular atmosphere for what is basically one image for the reader to visualize.

This second example is a version of the same opening of the same scene but with the focus of getting to the point swiftly so the reader can see the visuals in their head as quickly as possible.

The latter example is cinematic scene description.

Read More: Screenwriting Tips on Writing Action That Pops

4. Writing How a Film Editor Edits

Novice screenwriters often worry too much about the plot, as opposed to cinematically communicating that plot. They outline the scenes, make sure the proper plot points are placed here and there, and then when they write, they simply create scenes that lead the plot forward, often with dialogue that tells rather than shows.

This describes about 98% of the scripts floating around Hollywood agencies, management companies, and development offices right now.

The top 1% deliver on offering a hybrid of great concepts, great stories, great characters and great cinematic reads.

Film editing is a critical factor in the success of any film. Every choice the editor makes drastically affects the emotional engagement of any story, plot point, scene, sequence, or character.

The choices an editor makes are vital to the telling of a cinematic story. And it’s certainly not just about what is left on the cutting room floor, instead, it’s about vital yet straightforward choices like:

- When to enter and exit a scene

- How much or how little dialogue is used

- What emotions are shown

- What point of views are utilized

- What transitions are made from scene to scene, and what those transitions are telling us

These are choices that screenwriters need to make to create a more cinematic read that feels like the reader is watching the movie in its final cut.

It’s not about presenting camera angles and camera directions. It’s about presenting a visceral experience on the page. And this goes for any genre, including dramas.

5 Pro Screenwriting Tactics to Write How a Film Editor Edits

Offer a Visual Treat in the Opening Pages

Imagine the opening visual and conjure the dramatic, scary, thrilling or funny moments that follow. Imagine how you can quickly introduce characters while still showcasing elements of who they are. We covered this well in our blog posts How to Introduce Multiple Characters Quickly and How to Introduce Ensemble Characters in Dramas.

But even more important, offer something that engages the reader visually.

Here’s where most screenwriters make a mistake. They think that dialogue and some story point is a way to engage a reader in the opening pages. Human beings respond more to visual references. The best way to provide that cinematic experience is to conjure visuals that engage, rather than just some smart, interesting, or shocking dialogue or plot point.

You accomplish this by describing something that creates a visceral response in the reader. Something memorable. The late Wes Craven opened with this visceral scene in Scream that centered on the fear of being alone or stalked.

It’s cinematic because we don’t open with the setup of her character. We don’t meet her parents first. We don’t meet her boyfriend. We’re thrust right into the middle of the moment.

Case Study: The Thing

John Carpenter, the king of throwing us into the concept quickly, opened his classic sci-fi horror The Thing like this…

We aren’t introduced to the ensemble characters first. We aren’t introduced to their setting and group dynamics as a lesser script would have delivered.

- First, we’re offered a visual of a spaceship falling into Earth’s atmosphere.

- Then we’re immediately in the action of a helicopter chasing — and shooting at — a wolf.

- We watch as the wolf runs into the facility seeking refuge while the helicopter shooter exits and begins to fire at it while screaming at the main characters of the film in a foreign language.

- Finally, the shooter is taken out by one of the main characters.

This opening is accomplished almost entirely by visuals, and now we’re wondering how the visual of the spaceship entering Earth’s atmosphere is related to what followed. That’s cinematic.

Case Study: There Will Be Blood

Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood focuses solely on visuals as we are thrown into the lead character’s life.

We go from scene to scene of him:

- Surviving the elements

- Mining

- Getting hurt

- And then finally succeeding in finding his fortune.

It’s a visceral sequence that is edited perfectly as we:

- Wonder who this character is

- See how driven he is

- Learn that he’ll stop at nothing to succeed.

You, the writer, can and should write like these opening sequences are edited.

Intercut Different Scenes Together to Break Up Longer Scenes

If you have a more extended scene that needs to be featured, think like an editor and figure out how you can break up that scene by intercutting it with other scenes, jumping from location to location, from this character to that, etc.

Go from one to the other, back and forth, rather than just offering a bland collection of scenes built up on top of each other. That’s not how most great films feel when we’re in the theater. Why? Because they’ve been edited to convey a certain energy, flow, and style.

Don’t Edit from Plot, Edit from Instinct

As mentioned before, too many screenwriters focus on plotting the script out as they write and edit. Trust your instincts to create that cinematic “cut” of your script. What do you feel are the best cinematic choices when moving from one scene to the next? What works best visually?

The problem with supposed screenwriting “formulas for success” — Save the Cat, etc. — is that they breed formulaic screenplays. They teach you to write and edit from plot rather than from instinct. You’ve been watching movies and television your whole life. Trust this now-embedded visual storytelling instinct to offer answers to the sole question of “What do we see next?”

What Do We See Next?

It’s not about going to the outline to see what comes next in the story. It’s not about following some formula or structure. Writing like an editor edits is all about what we see next and why.

- Don’t be afraid to end a scene with a character gazing at the murky water and then opening the next scene on a close-up of that or another character washing their bloodied hands in the sink.

- Don’t be afraid to end a scene with a character threatening another in a violent rage and then open the next scene on that victim being discovered as a corpse floating in a lake.

Both examples that would otherwise be simple but effective film editing choices are types of visual elements that screenwriters should be embracing within each page of their script and every transition between scenes.

Pay Specific Attention to Rhythm

The great editor Walter Murch (Apocalypse Now) said it best when talking about editing:

“It’s all about rhythm.”

Some will say that great editing is seamless and unnoticeable. When we’re talking about rhythm, that rings true. For screenwriting, the same applies. However, sometimes following the rhythm of an emotional moment forces us to make transitions to scenes in a creative manner. Some emotional scenes play better if you jarringly cut to the next scene.

If someone is agitated after an argument with another character, the next scene could open with them back home, tearing apart their apartment. We don’t have to see them leave the previous location, walk home, enter, and then begin to wreak havoc. Instead, we go from the emotion of the argument to the emotion of their reaction sometime later.

Screenwriters can follow the emotional rhythm of the story and the character from scene to scene by making the right choices that offer cinematic transitions for the reader to easily comprehend.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed, and many Lifetime thrillers. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

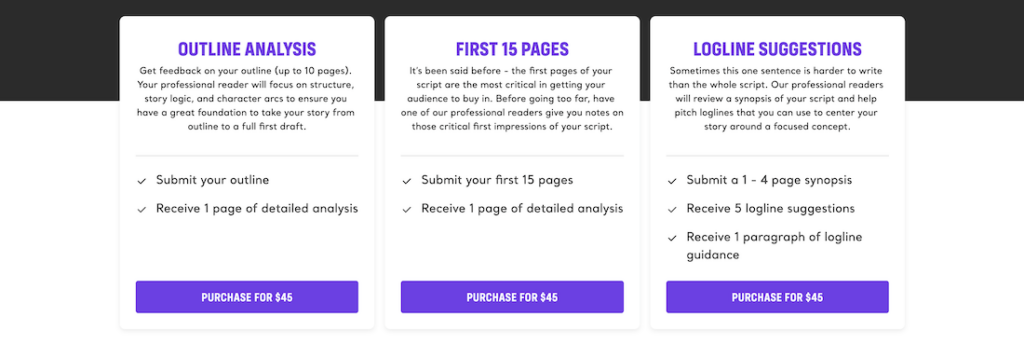

CHECK OUT OUR PREPARATION NOTES SO YOU START YOUR STORY OFF ON THE RIGHT TRACK!

The post Pro Screenwriting Tactics: How to Write Cinematically appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Ken Miyamoto