Beginning. Middle. End. That is the most simplistic way to open a discussion about the three-act structure. No matter what screenwriting philosophy you read, “secret” formula you apply, or structure you choose, no story can escape the master structure of the three-act story composition.

Screenwriters have multiple ways to tell their stories. And we’re not just talking about different platforms and formats like features, TV pilots, episodic series, limited series, etc. Nor are we discussing the multiple genres in which you can place your characters, worlds, and stories. Here we will delve into the dynamics of the three-act structure and try to simplify it so you can master it within your screenplays.

Read More: 10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use

Got a great feature spec? Enter it into the ScreenCraft Feature Screenplay Competition!

Where Did Three-Act Structure Come From?

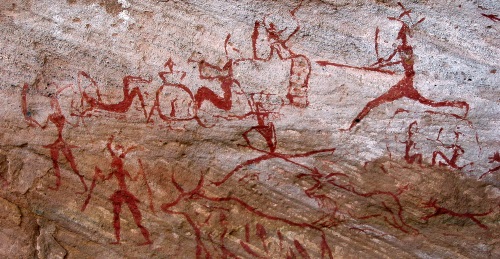

This story structure has been utilized in humankind’s storytelling since the dawn of our existence when we began to tell stories around the fire in caves, camps, and villages. This history is evident in archeological cave etchings that define the three-act structure in visual form.

- Hunters preparing for the hunt with spears and weapons (beginning).

- Hunters confronting the dangers of the prey (middle).

- Hunters defeating the prey (end)

You can expand upon this simple breakdown in equally simplistic definitions as well.

- Characters are introduced in their world (first act).

- They then face conflict and confrontations that rock their world (second act).

- They learn from their mistakes and missteps, adapt, and defeat the conflict they face (third act) — unless it’s a tragedy.

Aristotle’s Poetics & Three-Act Structure

Aristotle — the Greek philosopher, scientist, and master storyteller — is often called the father of the three-act structure. His book Poetics delved into the analysis of epic storytelling and tragedies. These forms of storytelling were presented to the public of his time — poetry and the stage.

The great philosopher stated that the best storytelling involved artistically constructed incidents that produced the essential tragic effect found within the most significant plays and stories. He pointed out that the core structure of a story’s plot involved a beginning, middle, and end.

Read More: What Is a Plot?

Screenwriting is a cousin to the plays of Aristotle’s time and the hundreds of years of stage and theatre storytelling that followed. Structure was necessary to tell a story within a play’s limited time. Screenplays are even more constrained by time, with the average film ranging from 90 to 120 minutes, with most longer movies going only 30-45 minutes beyond that.

A three-act structure helps to organize pivotal events within the story to create a well-paced visual experience that builds to a climax.

Other story structures include four-act, five-act, six-act, and seven-act variations. Additional structure options can flip the end to the beginning or create more visceral cinematic experiences by telling a story out of sequence in different ways using structure tweaks like flashbacks, flashforwards, dream sequences, and many other creative alternatives.

However, none of these variances can escape the three-act structure.

In 1979, author Syd Field wrote one of the best-selling screenwriting books in history, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Field embraced the three-act structure in the book and broke it down into three sections.

- Setup (Act I): You set up the characters and establish their goals. You also showcase their ordinary world so that we can see how affected they are by the conflict(s) they are about to face.

- Confrontation (Act II): The characters are confronted by the conflict(s), and the story escalates as the stakes grow higher amidst the confrontations they are involved with.

- Resolution (Act III): Everything within the first and second acts is resolved. The characters either triumph or falter (as with tragedies).

That is the most general definition of the three-act structure.

The Three-Act Structure Is NOT a Formula

Screenwriters should never mistake the three-act structure as a formula.

Read More: How Rocky Debunks the Save the Cat Formula

Formulas are story options that work under the umbrella of the three-act structure, just as other story structures do. The three-act structure is the basic understanding of story structure at its core. Each act serves the next. And within the preceding act, or anything to build towards in the third act, the story is less effective and more disjointed.

Star Wars (1977)

Why Use the Three-Act Structure?

The three-act structure gives you the most basic story organization for your screenplay. It’s a virtual compass that guides your process, characters, stories, and plots.

These three acts help you sectionalize your story. And within each act, you can effectively employ additional plot points to drive the story toward its necessary conclusion.

Development questions like:

- “Where does my story begin?”

- “Where does my story end?”

- “What happens in between the beginning and end?”

These are all answered by looking at your story through the lens of the three-act structure. They help you answer additional development questions like:

- “Where are the characters before the major conflict hits them?” (finding the first act)

- “How can I raise the stakes to keep audiences invested?” (finding the second act)

- “What is the best way to end the story?” (finding the third act)

These questions also help you pin down and edit those broader worlds you may have been creating. They allow you to pinpoint the part of the characters’ lives you want to showcase. And then also help you to find the essential story and character elements you’ll be able to include within the confines of what will eventually be a 90-120 minute cinematic story.

What to Include in Act I/II/III

The great thing about focusing less on formulas and sub-structures and more on three acts is that you can utilize additional plot points and moments as needed within your story, as opposed to following a step-by-step or paint-by-the-numbers approach. There is more freedom to it. And you can utilize variations of different formulas and sub-structures within.

Save the Cat and The Hero’s Journey are the two most highly utilized formulas or sub-structures. There are dozens of variations of them as well. But they all fall under the three-act umbrella.

The broad strokes of each of the three acts include:

Act I

The first act briefly sets up the characters, the world they live in, and establishes the characters’ wants and needs. It’s essentially the start of their internal and external character arcs. The internal and external conflicts they will be facing can also be introduced in the first act as well.

You generally want to keep the first act to a minimum, allowing the characters’ actions and reactions to define their characters, as opposed to overuse of exposition and back story. Remember, it’s a movie. And the audience wants to get to the juiciest parts of the story as quickly as possible. You don’t need to waste too much time with back story.

Read More: Defining Character Through Action: There Will Be Blood

Act II

The second act is the longest of the three and has the characters facing the conflict head-on, with increasing stakes that put them in more physical, mental, or emotional peril. Traditionally, the end of the second act will leave the characters at their lowest point. However, they have learned a lot about themselves and the conflict(s) they are facing.

To keep script readers and audiences engaged, you can use the second act to create additional plants, payoffs, and twists to keep things interesting.

Read More: 101 Great Plot Twist Ideas

Act III

The third act is where the story is resolved. The characters take what they’ve learned and try to apply those lessons to defeat, conquer, or surpass the conflict(s) they have faced. This is the act with the climax, be it emotional or physical. The story is resolved by the characters achieving an inner or outer goal (preferably both), defeating the conflict (emotionally or physically), or succumbing to the conflict (when the story is a tragedy that ends with a tragic loss).

It’s important to know that you’ll read a hundred different things that each act must have — but there are no secret formulas, necessary beats, or particular page counts where story elements need to happen. All that is figured out within your process as you develop your story and write your script. What worked for one script or movie may not work for the story you are trying to tell.

Again, that is what is so great about the three-act structure. There’s plenty of room to maneuver your story and characters within each act instead of trying to hit particular story points by specific pages.

The Three-Act Structure of Top Gun: Maverick

While Top Gun: Maverick is a sequel, the actual story is far removed from the original film’s story and could have just as easily been an original movie about a fighter pilot dealing with demons from his past. The sequel elements are minimal, beyond character history that drives the actions and reactions of Maverick.

With that in mind, here we present the simple three-act breakdown of Top Gun: Maverick.

First Act

We are introduced to Maverick’s ordinary world. He’s not a Top Gun instructor. In fact, he’s at the end of his career. Because of his maverick ways, he has ruined any potential leadership roles after years of continual insubordination. He’s now relegated to the role of a test pilot in a program about to be disbanded. Despite his heroic — yet insubordinate — efforts to attain the program’s goals, Maverick is ordered back to Top Gun.

Upon arriving, he’s informed that he has been assigned to instruct a group of Top Gun pilots to undergo a seemingly impossible mission. Maverick reconnects with an old flame and is about to face a person from his past — the son of his best friend, Goose, who died tragically thirty years prior while Maverick was piloting their jet. Upon seeing Rooster, Goose’s son, it’s clear that Maverick is still dealing with guilt and loss.

By the end of this first act, we know what conflicts Maverick will face. We also see how these conflicts oppose his ordinary world, where he was happy living under the radar doing what he does best. Lastly, we know he’s about to face people from his past.

Second Act

The second act begins as Maverick arrives to instruct the pilots. He faces his estranged adopted son, Rooster, and there is instant conflict between them. Maverick also faces confrontations with his superior officer, as well as with the training of the pilots in a mission that seems to be more and more surefire suicide.

Maverick learns from his mistakes — primarily through the guidance of his previous wingman Iceman, now the commanding Admiral of the Navy Fleet — and finds ways to train the pilots properly. However, more and more conflicts arise as Maverick and the pilots try to find ways to make this impossible mission more plausible.

He turns to his old girlfriend, Penny, to help him through the ongoing conflict while building a potential post-Navy life with her.

But the stakes keep getting raised. Iceman dies. Maverick is released from the mission when his superior officer changes the mission parameters, which Maverick knows means certain death to Rooster and other pilots. This is where the characters of Maverick, Rooster, and the other pilots are at their lowest.

Third Act

When the mission briefing begins — with Maverick now released — the pilots are shocked to see that Maverick has taken a jet to prove to his superior officer that the mission can succeed under the original parameters. He flies the lead jet formation with seconds to spare, proving that not only is the mission possible with the original safer parameters, but he is the one to lead the team.

The mission begins. They complete it successfully. But now the pilots are tasked with getting out alive. Additional stakes are raised when Maverick — and eventually Rooster — are shot down in enemy territory. They steal an old F-18 and battle their way back to their U.S. aircraft carrier.

The story is resolved. The external arc of the story is complete as Maverick has successfully trained the pilots — and the mission was a success with no loss of life along them. The internal arc of Maverick is complete, as he has regained his relationship with Rooster and has now found a new life with him and with Penny.

—

The three-act structure is simple, with nuanced elements that you can apply to the beginning, middle, and end of your screenplays. Since it is the ultimate master structure of all stories, you can find ways to adapt it to fit the needs of your story, giving you structure and direction to achieve Aristotle’s collection of “artistically constructed incidents” that make up a compelling and engaging story.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, and Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries BLACKOUT, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, the feature thriller HUNTER’S CREED, and many produced Lifetime thrillers. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies and Instagram @KenMovies76.

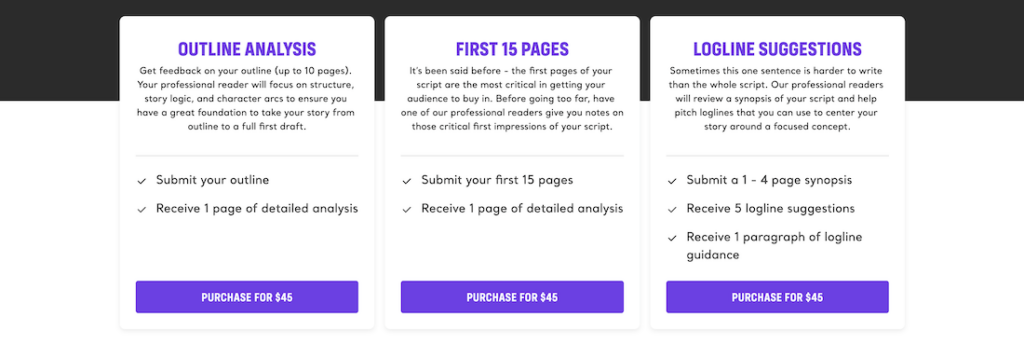

CHECK OUT OUR PREPARATION NOTES SO YOU START YOUR STORY OFF ON THE RIGHT TRACK!

The post What is Three-Act Structure and How Do You Use It in Screenwriting? appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Ken Miyamoto