Unlocking the Secrets of the Heart: A Poetic Journey Beyond Medicine by P.K. Deb

The long-term illness of my wife pours instantly a course of cursed ink on my…

Uncover the Hidden Message in G. S. Katz’s “Land Line” That Will Change How You See Connection Forever

Land line, corded phone Clarity I can actually hear you Expensive to still own But…

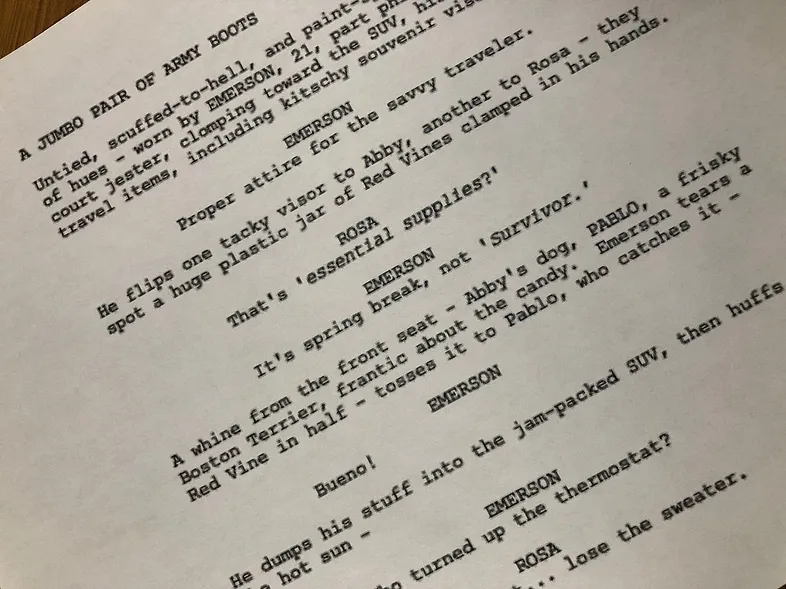

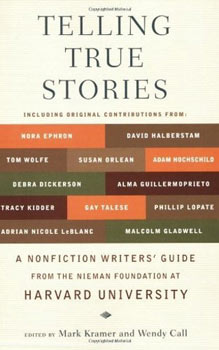

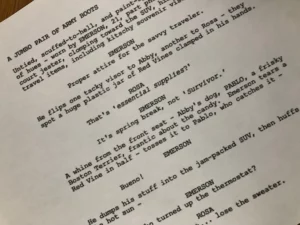

Unlock Hollywood Secrets: Dennis Foley’s Ultimate Screenwriting Masterclass Revealed

“Hollywood is the only town where you can not fail. You can only quit trying.”Continue…

Unveiling Summer’s Secret Arrival: A Poetic Journey by G. S. Katz

sultry heat skin attraction gaze lean stares gelato watermelon dirty martinis low cut bbq old…

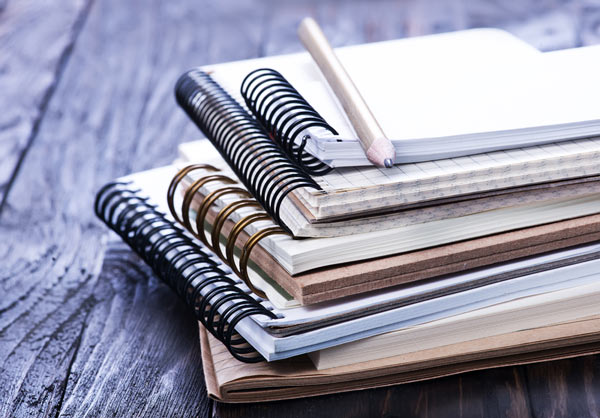

The Surprising Secret Behind Why Your Writing Space Could Make or Break Your Creativity

The wrong writing space can kill your imaginationContinue reading on The Writing Cooperative »

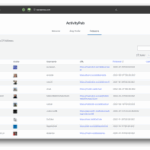

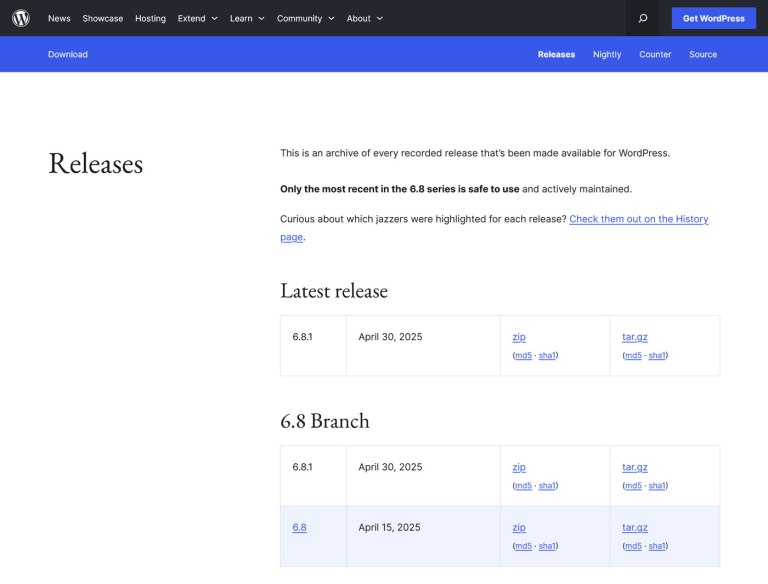

Unlock the Future of WordPress: Discover the 3 Game-Changing ActivityPub Features You Can’t Miss!

Imagine publishing once and instantly reaching engaged readers across dozens of platformsâwithout ads, algorithms, or…

Unlock the Secret Ingredient That Transforms Ordinary Writing into Irresistible Masterpieces

Your writing voice is how you express yourself and your ideas in writing. It’s about…

Unveiling the Hidden Depths: Discover the Identity Within G. S. Katz’s Poem “It’s Who I Am”

cajole flatter fill the void of your emptiness favorite song on the radio a cool…

Unlock the Mystery: Can You Solve the WritersWeekly Trivia Question for 07/17/2025?

According to this week’s issue, which company tried to scam an author out of $18K…

Unlock Hidden Remote Writing and Editing Opportunities You Didn’t Know Existed – July 17, 2025 Edition

ALERT!!! THE SUMMER, 2025 24-HOUR SHORT STORY CONTEST IS THIS SATURDAY! Only 500 participants are…