At their core, scary stories all strive to shake us up on a visceral level. They do this by way of many concepts, vibes, tropes and tricks of language that subtly eat away at our minds to unsettle us. On the surface, however, most horror stories of course, frequently hinge on how scary, unique, fun, cool and/or violent the villain happens to be.

Godzilla (2014)

Are they a tentacled beast from the depths of the sea? Are they an old god with cosmic powers? Are they a rotting bulk of a man in coveralls that you cannot seem to kill? Are they a regular person driven to be murder-y? Are they a displaced soul in a child’s doll? Are they a car imbued with the essence of evil? Be they ghosts, vampires, masked slashers, drug-addled forest creatures, or some beast yanked from mythology – knowing your antagonist is essential before writing a scary story. In horror films especially, much of the motivation for your leads is going to be rooted in how they react to the danger they are faced with.

Read More: The Art of Writing Horror: Constructing a Scare

Generally speaking, your characters are going to be at a disadvantage until the end of the movie. Horror stories belong to the thing that is the source of the horror – even if we don’t see them. In fact, we shouldn’t see them too much in the first half… but that doesn’t mean we aren’t seeing a world affected by their existence.

This is why you have to know your monster.

Halloween Kills (2021)

The best thing about monsters is that you can literally make anything up and be on the right path. You can use something from mythology or you can put a new spin on an old trope – whatever floats your boat. It’s also been repeatedly proven that you can take a very traditional, maybe even over-used monster like a vampire, a slasher, or a zombie and completely change the known rules and tropes. Remember when zombies didn’t run and vampires didn’t sparkle? Do what you want!

But what if you don’t know what you want?

The Four Categories of Monsters

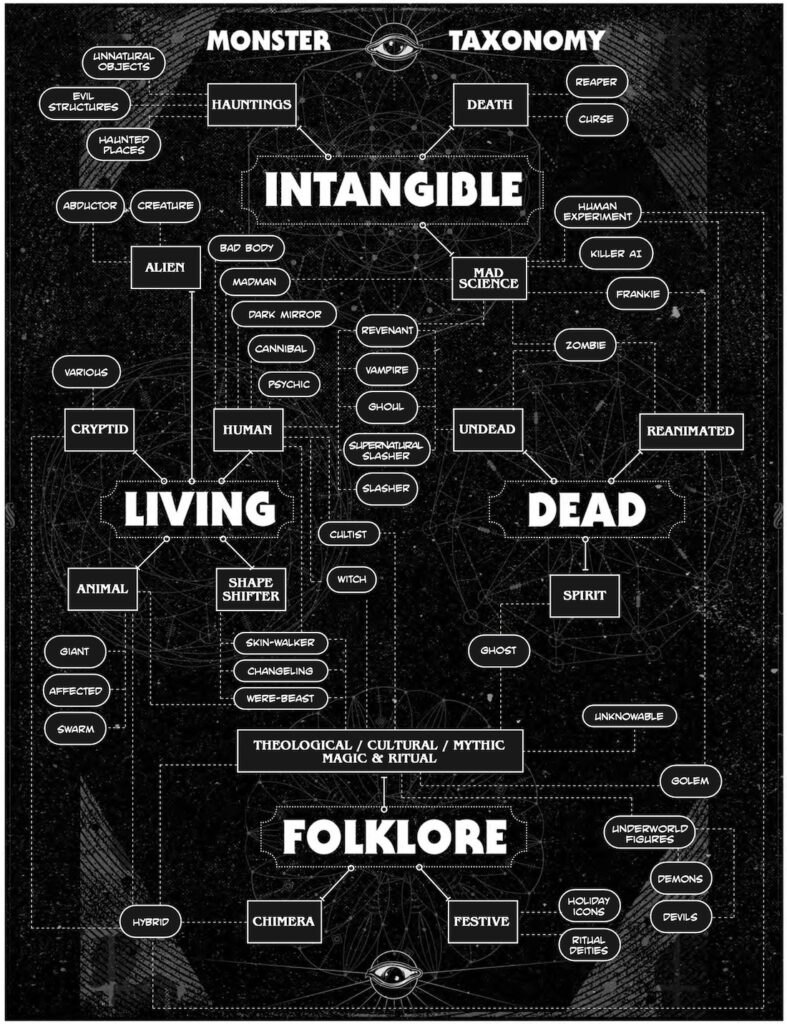

Luckily for you, I’ve over-thought this very issue many, many times for myself, and I’m of the opinion that all monsters/antagonists in horror films can fit into a pretty tight taxonomy. At the top level, there are only four categories: The Intangible, The Living, The Dead and things from Folklore.

The Intangible covers conceptual evils — hauntings that are pure bad vibes, the notion of death, science gone wrong, or the essence of evil sans a personality that imbues structures or objects.

The Living covers all many of bad humans, animals, cryptids, and shapeshifters. This includes people with powers or magic on their side or anything that has a heart that pumps blood.

The Dead is obvious — it covers reanimation, the undead, ghosts, spirits or anything that was once living and is somehow still around after not being alive anymore.

Folklore is a wide classification as it includes mythology, theology, specific cultures and religions— so anything from demons and devils to chimera and monstrous legends to unknowable otherworldly space Gods.

Obviously, there is all sorts of overlap between these things, and the categorizations are kind of loose. And because I am a weirdo with too much time on my hands (yay, strikes!), I’ve even made a chart:

What Kind of Monster Fits Your Story?

So what kind of monster does your story need? Despite this complicated and expertly-organized chart, when it comes to writing your monster there are really only four different ways to go about portraying them. These four choices dictate which paradigm to follow, but also feel free to choose the one that best fits the kind of story you want to tell. A few outliers aside, almost every monster/antagonist in a horror film every scene fits into one of these “villain paradigms.”

1) The Bad Guy

Despite a monstrous nature, this creature has the mind of a human. Like any good antagonist, they should think they are the hero of the story, or at the very least, need something that they consider more important than human lives. The best way to develop this kind of character is to put them through the same sort of arc-planning as your lead character.

Give them motivation. (Keep in mind, “guy” is a gender-neutral term here and this is just the name of the paradigm.)

The Blob (1958)

2) The Unstoppable Force

Great for slashers, survival horror, and creature features, this angle treats your monster as something propelled by a SINGLE motivator. What’s fun is the audience could know what that motivator is, or not. What did The Blob want other than to absorb people and get bigger? All we really know is that they don’t stop. Generally, you want to find an arc where they may be more mysterious or weak at first and grow (perhaps literally) as the story chugs along.

3) From Darkness

This strategy is all about the monsters that hide in the dark. It’s possible they are smart like a person, but most likely are some sort of lesser intelligence. But they should be smart enough to know how to track, hunt, and strike at just the right moment. Think snatch and grab – you want isolated kills. Its arc should lead to it being more like an unstoppable force in the third act of your story. Generally, they have a task or habit they are enacting or are satisfying some sort of need.

4) Cause and Effect

Something has started the evil on its path and will continue until it is put away again or stopped. It will start quiet, and stay hidden (sometimes in plain sight) or look innocent at first, then will become more overtly evil and dangerous as the story progresses. If intelligence is a factor it will get more clever as time passes. It usually wants something very specific and will get it by any means necessary.

Child’s Play (1988)

Whether we are talking about a giant monster stomping a city to bits, a possessed doll hiding in a child’s room, or a ghost with a grudge, the final piece is the point of view.

Read More: 9 Simple Lessons for Writing Effective Horror Screenplays

The more an audience sees and knows, the less scary things are, so always remember to arc the tension around a monster. Godzilla, Michael Myers, and a Xenomorph all have very different applications of screen time. It all depends on the type of movie you writing, and how you want to play with tension — is it a rollercoaster or a sweeping arc of anxiety?

Alien vs. Predator (2004)

Writing films comes down to making choices. Writing horror films comes down to making choices with the intent to scare people, so drop some bodies and scare away!

Additionally, if you’d like to read more about crafting horror films, check out my free-to subscribe substack.

The pieces there, as well as this article, are all slightly edited versions of chapters of my book, The Scary Movie Writer’s Guide.

It’s a 115-page workbook full of activity sheets, quizzes, exercises and practices designed to help anyone go from generating ideas to writing a full outline to write their own horror film. If you’re interested in more, you can buy the book here.

Read More: A Horror Writer’s Responsibility: What to Consider When Writing Violence

Get professional notes on your horror script!

The post How to Make a Monster appeared first on ScreenCraft.

Go to Source

Author: Seth M. Sherwood